Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients (40 page)

Read Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

There is every reason to believe that this is an underestimate. If a stranger contacted you out of the blue, and asked you to admit career-torpedoing antisocial and unethical behaviour from your work email address, you might be a little reluctant. A guarantee of anonymity from someone you’ve never heard of and never met is small reassurance against the real and foreseeable consequences of confessing all. So respondents may have dishonestly denied involvement in ghostwriting. And there is every reason to believe that the 30 per cent of study authors who declined to participate at all were more likely to have been involved in ghostwriting.

Another study from 2007 took all the industry-funded trials approved by ethics committees in two Danish cities, and compared the people documented as prominently involved in the trials against those listed as authors on the academic papers reporting their results, finding evidence of ghost authorship in 75 per cent of cases:

76

the company statisticians, the company staff who designed and wrote the protocol for the trial, and the commercial writers drafting the manuscript would somehow disappear when the final paper was published, to be replaced by neat, independent academics.

Since this activity is so hard to trace, it is, I think, legitimate simply to ask people who work with academic authors about their experiences. One editor-in-chief of a specialist journal told US Senate Finance Committee staff recently that in his estimation at least a third of all papers submitted to his journal were produced by commercial medical writers, working on behalf of a drug company.

77

The editor of the

Lancet

described the practice as ‘standard operating procedure’.

78

It’s worth pausing for a moment here to think about why ghostwriting is used. If you saw that an academic paper describing a new scientific study was designed, conducted and written by drug-company employees, you would be very likely to discount its findings. At the very least, alarm bells would be ringing, and you’d worry more than usual about whether there was data missing, or a flattering emphasis placed on the results. If you were reading an opinion piece explaining why a new drug is better than an old one, and you saw that it was written by someone from the company making the new drug, then in all likelihood you’d laugh at it. This, you would mutter, is a promotional piece. What’s it even doing in an academic journal?

In this context, it’s not hard to understand the language, strategies and intentions of people producing these papers. Generally, a ‘Medical Education and Communication Company’ will get involved early on in the research process, to help plan a whole programme of apparent academic publications around the marketing of a drug. This is to lay the groundwork, as we’ve already seen – to produce papers arguing that the condition being treated is more common than previously thought, and so on. It will also go through the quantitative data available from each study, to look at how it might be sliced up. A good publication planner will help identify ways that more than one paper could be produced from each piece of research, so creating a broader palette of promotional opportunities.

This is not to say that the ghostwriter will see all the data: in fact, one of the extra benefits of this way of working – from a company’s perspective – is that the writer will often only see tables and results that have already been prepared by a company statistician, tailored to tell a specific story. This is, of course, just one way in which the production of a paper by company personnel differs from the normal run of academic work.

At this stage of proceedings the discussion is generally between the company and the commercial writing agency. After a plan has been made, and articles outlined, both will set about identifying academics whose names can go on their papers. For an experiment, or a piece of research, there may already be some academics involved. For an editorial, a review article or an opinion piece, the articles can be devised and even drafted autonomously. Then they will be delivered to the waiting academic for some comments, and most importantly of all, for their name and independent status to be used as author and guarantor of the work.

Writing an academic paper is a long and arduous business for the lecturers and professors who actually do it themselves. First, you have to review the literature for a whole field, avoid embarrassing omissions, and write a coherent introduction to your paper describing the work that has gone before. This is of course a golden opportunity to frame the field. Then, if it’s a report of a piece of research, you have to conduct the work – which can take forever – get through all the bureaucratic hurdles, the ethics committees, coordinate the data collection, and more. Finally you have to get the data into a state where it can be analysed, find and clean the errors and duplicates, run the analysis, and build tables (my God, the days I have wasted making tables work). Before that, you need to decide what tables to make, which findings to highlight, and more. After all that, you need a discussion section that makes sense of the findings, discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the methods, and so on. Even for a straight opinion piece or a casual review article, you need to have the idea, and the time, in the first place.

After the paper is written, the horror begins. Several colleagues who have their name on it will have small comments, suggestions, tweaks. These will all come in at random times on email, and everyone’s suggestion has to be approved by everyone else. All papers go through multiple drafts, maddeningly similar, and you can never be sure if someone has introduced an insane sentence that you might miss on a casual reading, so it all has to be checked – and rechecked – competently, and repeatedly.

Finally, the submission process is a pig. Every academic journal has different pernickety requirements; every one wants the references to be formatted in a different way – the tables as a separate document, at the bottom, there’s a word limit, some bizarre house style about never using the word ‘this’ to back-reference the immediately preceding clause, even though that’s a completely normal way of using the English language, and so on.

Because of all this, academics don’t produce a huge number of papers every year, even though their performance is measured specifically on how many they get out, and how good they are. For that very reason, you should perhaps be a little suspicious of any academic who publishes a lot of papers, at the same time as holding down a clinical job seeing patients.

So professional assistance, for this arduous process, is a huge advantage; and this is why the selection of the academic or doctor who receives ‘guest authorship’, benefiting from the ghostwriter’s work, is a complex and interesting business. They are not picked at random: as we shall see, drug companies keep a close rota of ‘key opinion leaders’, academics and doctors who are influential in their field, or their local area, and are friendly to either the company or the drug.

The relationship between the key opinion leader and the drug company is mutually beneficial, in ways that are hard to see at first. Of course the drug company is able to give a false impression of independence for a paper that it effectively conceived and wrote, and of course money can change hands. (Did I not mention that? Some academics are paid an ‘honorarium’ by the drug company for putting their name on a paper.) But there are other, more hidden benefits.

The academic gets a publication on their CV, for very little work, so they look like a better academic. They are more likely to be recognised as a key opinion leader in the future – which is great for the company, since they’re friends – and they are also more likely to be promoted in their university. A junior lecturer with an impressive record of academic journal publications will be much more likely to get on and become a senior lecturer, and then a ‘reader’, and then a professor. By this means the ambitious academics receive a benefit in kind, as good as any cheque, for which they are grateful to the drug company. Most importantly of all, the key opinion leader, who has the opinions that benefit the company, becomes much more senior and influential, a rising star.

I wouldn’t want you to take any of this on faith. Most of the activity in this field takes place behind closed doors, but occasionally there are court cases, and from these come leaked documents, and sometimes, if we are lucky, emails and memos describing the ghostwriting process. As I’ve said before, nothing should be read into the specific drugs or companies involved in the stories here, because the activity they describe is, as we can see from the data above, widespread throughout the industry, for all companies and in all fields of medicine. These are simply the individual drugs for which we happen to be able to see, in black and white, the internal memos and discussions that lie behind the ghostwritten papers, and keeping documents on these matters out of the hands of people like me is, incidentally, one reason why companies tend to settle out of court, and avoid a public hearing where such documents are likely to be exposed.

*

One interesting example comes from the antipsychotic drug olanzapine (brand name Zyprexa), used to treat conditions like schizophrenia.

80

Lots of documents on the ghostwriting strategy of Lilly, the drug’s manufacturer, became public during a court case concerned with whether it had overstated the benefits of the drug, and marketed it for conditions where it wasn’t licensed.

Lilly set a goal of making Zyprexa ‘the number one selling psychotropic in history’, and its emails discuss using ghostwriters to present it in a positive light: ‘The paper for the Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry supplement has been completed and sent to the journal for peer review,’ says one from its marketing person. ‘We “ghost” wrote this article and then worked with author Dr Haddad to work up the final copy.’

The paper being talked about did appear in a supplement to the journal

Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry

. Peter Haddad, whose name appears as its author, is a consultant psychiatrist in Manchester, seeing patients and training junior doctors.

81

He’s neither very senior, nor very junior, and I’m not telling you his job because I think it’s an outrage, or because I think it makes him sound impressive: I’m telling you because this is the banal, everyday reality of how this process works, with everyday doctors playing their part, around the country. The emails explain how Lilly’s global team approved the draft of Peter’s paper, but final approval had to come from Lilly UK, since the journal was based in the UK. Nice work, Peter Haddad.

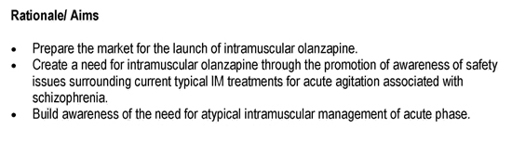

From the same case, there is also an entire briefing document discussing how Lilly will place an article saying that the injectable form of olanzapine might be useful in containing challenging behaviour when people with schizophrenia are very agitated and disturbed.

82

I recommend downloading this online if you have any doubts about the truth of what I’ve been saying, or about the casual way in which these projects are pursued. Remember that the subject of this document is an article to be written by an independent academic. The company lists its aims, and they don’t sound very academic:

It talks about how to work around the fact that the drug isn’t yet licensed:

It attaches an outline that can be used as a guide to write the pieces (because, remember, there may be many similar articles in this aspect of the publication plan, written by different people in different countries):