Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients (10 page)

Read Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

Later in 2003, GSK had a meeting with the MHRA to discuss another issue involving paroxetine. At the end of this meeting, the GSK representatives gave out a briefing document, explaining that the company was planning to apply later that year for a specific marketing authorisation to use paroxetine in children. They mentioned, while handing out the document, that the MHRA might wish to bear in mind a safety concern the company had noted: an increased risk of suicide among children with depression who received paroxetine, compared with those on dummy placebo pills.

This was vitally important side-effect data, being presented, after an astonishing delay, casually, through an entirely inappropriate and unofficial channel. GSK knew that the drug was being prescribed in children, and it knew that there were safety concerns in children, but it had chosen not to reveal that information. When it did share the data, it didn’t flag it up as a clear danger in the current use of the drug, requiring urgent attention from the relevant department in the regulator; instead it presented it as part of an informal briefing about a future application. Although the data was given to completely the wrong team, the MHRA staff present at this meeting had the wit to spot that this was an important new problem. A flurry of activity followed: analyses were done, and within one month a letter was sent to all doctors advising them not to prescribe paroxetine to patients under the age of eighteen.

How is it possible that our systems for getting data from companies are so poor that they can simply withhold vitally important information showing that a drug is not only ineffective, but actively dangerous? There are two sets of problems here: firstly, access for regulators; and secondly, access for doctors.

There is no doubt that the regulations contain ridiculous loopholes, and it’s dismal to see how GSK cheerfully exploited them. As I’ve mentioned, the company had no legal duty to give over the information, because prescription of the drug in children was outside of paroxetine’s formally licensed uses – even though GSK knew this was widespread. In fact, of the nine studies the company conducted, only one had its results reported to the MHRA, because that was the only one conducted in the UK.

After this episode, the MHRA and the EU changed some of their regulations, though not adequately. They created an obligation for companies to hand over safety data for uses of a drug outside its marketing authorisation; but ridiculously, for example, trials conducted outside the EU were still exempt.

There is a key problem here, and it is one that recurs throughout this section of the book: you need

all

of the data in order to see what’s happening with a drug’s benefits, and risks. Some of the trials that GSK conducted were published in part, but that is obviously not enough: we already know that if we see only a biased sample of the data, we are misled. But we also need all the data for the more simple reason that we need

lots

of data: safety signals are often weak, subtle and difficult to detect. Suicidal thoughts and plans are rare in children – even those with depression, even those on paroxetine – so all the data from a large number of participants needed to be combined before the signal was detectable in the noise. In the case of paroxetine, the dangers only became apparent when the adverse events from all of the trials were pooled and analysed together.

That leads us to the second obvious flaw in the current system: the results of these trials – the safety data and the effectiveness data – are given in secret to the regulator, which then sits and quietly makes a decision. This is a huge problem, because you need many eyes on these difficult problems. I don’t think that the people who work in the MHRA are bad, or incompetent: I know a lot of them, and they are smart, good people. But we shouldn’t trust them to analyse this data alone, in the same way that we shouldn’t trust any single organisation to analyse data alone, with nobody looking over its shoulder, checking the working, providing competition, offering helpful criticism, speeding it up, and so on.

This is even worse than academics failing to share their primary research data, because at least in an academic paper you get a lot of detail about what was done, and how. The output of a regulator is often simply a crude, brief summary: almost a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ about side effects. This is the opposite of science, which is only reliable because everyone shows their working, explains

how they know

that something is effective or safe, shares their methods and their results, and allows others to decide if they agree with the way they processed and analysed the data.

Yet for the safety and efficacy of drugs, one of the most important of all analyses done by science, we turn our back on this process completely: we allow it to happen behind closed doors, because drug companies have decided that they want to share their trial results discretely with the regulators. So the most important job in evidence-based medicine, and a perfect example of a problem that benefits from many eyes and minds, is carried out alone and in secret.

This perverse and unhealthy secrecy extends way beyond regulators. NICE, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, is charged with making recommendations about which treatments are most cost-effective, and which work best. When it does this, it’s in the same boat as you or me: it has absolutely no statutory right to see data on the safety or effectiveness of a drug, if a company doesn’t want to release it, even though the regulators have all of that data. As a result, NICE can be given distorted, edited, biased samples of the data, not just on whether a drug works, but also on how likely it is to have unpleasant side effects.

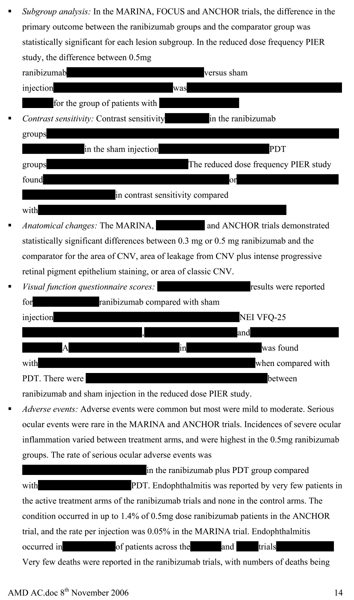

Sometimes NICE is able to access some extra unpublished data from the drug companies: this is information that doctors and patients aren’t allowed to see, despite the fact that they are the people making decisions about whether to prescribe the drugs, or are actually taking them. But when NICE does get information in this way, it often comes with strict conditions on confidentiality, leading to some very bizarre documents being published. On the next page, for example, is the NICE document discussing whether it’s a good idea to have Lucentis, an extremely expensive drug, costing well over £1,000 per treatment, that is injected into the eye for a condition called acute macular degeneration.

As you can see, the NICE document on whether this treatment is a good idea is censored. Not only is the data on the effectiveness of the treatment blanked out by thick black rectangles, in case any doctor or patient should see it, but absurdly, even the names of some trials are missing, preventing the reader from even knowing of their existence, or cross referencing information about them. Most disturbing of all, as you can see in the last bullet point, the data on adverse events is also censored. This is a perfectly common state of affairs, and I’m reproducing the whole page here because I worry that it would otherwise be almost too bizarre for you to believe.

Why shouldn’t we all – doctors, patients and NICE – have free access to all this information? This is something I asked both Kent Woods from the MHRA, and Hans Georg Eichler, Medical Director of the European Medicines Agency, in 2010. Both, separately, gave me the same answer: people outside the agencies cannot be trusted with this information, because they might misinterpret it, either deliberately or through incompetence. Both, separately – though I guess they must chat at parties – raised the MMR vaccine scare, as the classic example of how the media can contrive a national panic on the basis of no good evidence, creating dangerous public-health problems along the way. What if they released raw safety data, and people who don’t know how to analyse it properly found imaginary patterns, and created scares that put patients off taking life-saving medication?

I accept that this is a risk, but I also believe their priorities are wrong: I think that the advantages of many eyes working on these vitally important problems are enormous, and the possibility of a few irrational scaremongers is no excuse for hiding data. Drug companies and regulators also both say that you can already get all the information you need from regulators’ websites, in summary form.

We shall now see that this is untrue.

Two: Regulators make it hard to

access the data they do have

When exposed to criticism, drug companies often become indignant, and declare that they already share enough data for doctors and patients to be informed. ‘We give everything to the regulator,’ they say, ‘and you can get it from them.’ Similarly, regulators insist that all you need to do is look on their website, and you will easily find all the data you need. In reality, there is a messy game, in which doctors and academics trying to find all the data on a drug are sent around the houses, scrabbling for information that is both hard to find and fatally flawed.

Firstly, as we’ve already seen, regulators don’t have all the trials, and they don’t share all the ones that they do. Summary documents are available on the early trials used to get a drug onto the market in the first place, but only for the specific licensed uses of the drug. Even where the regulator has been given safety data for off-label uses (following the paroxetine case above) the information from these trials still isn’t made publicly available through the regulator: it simply sits quietly in the regulator’s files.

For example: duloxetine is another SSRI drug in fairly widespread use, which is usually given as an antidepressant. During a trial on its use for a completely different purpose – treating incontinence – there were apparently several suicides.

66

This is important and interesting information, and the FDA hold the relevant data: it conducted a review on this issue, and came to a view on whether the risk was significant. But you cannot see any of that on the FDA website, because duloxetine never got a licence for use in treating incontinence.

67

The trial data was only used by the FDA to inform its internal ruminations. This is an everyday situation.

But even when you are allowed to see trial results held by regulators, getting this information from their public websites is supremely tricky. The search functions on the FDA website are essentially broken, while the content is haphazard and badly organised, with lots missing, and too little information to enable you to work out if a trial was prone to bias by design. Once again – partly, here, through casual thoughtlessness and incompetence – it is impossible to get access to the basic information that we need. Drug companies and regulators deny this: they say that if you search their websites, everything is there. So let’s walk, briefly, through the process in all its infuriating glory. The case I will use was published three years ago in

JAMA

as a useful illustration of how broken the FDA site has become:

68

replicating it today, in 2012, nothing has changed.

So: let’s say we want to find the results from all the trials the FDA has, on a drug called pregabalin, in which the drug is used to treat pain for diabetics whose nerves have been affected by their disease (a condition called ‘diabetic peripheral neuropathy’). You want the FDA review on this specific use, which is the PDF document containing all the trials in one big bundle. But if you search for ‘pregabalin review’, say, on the FDA website, you get over a hundred documents: none of them is clearly named, and not one of them is the FDA review document on pregabalin. If you type in the FDA application number – the unique identifier for the FDA document you’re looking for – the FDA website comes up with nothing at all.

If you’re lucky, or wise, you’ll get dropped at the Drugs@FDA page: typing ‘pregabalin’ there brings up three ‘FDA applications’. Why three? Because there are three different documents, each on a different condition that pregabalin can be used to treat. The FDA site doesn’t tell you which condition each of these three documents is for, so you have to use trial and error to try to find out. That’s not as easy as it sounds. I have the correct document for pregabalin and diabetic peripheral neuropathy right here in front of me: it’s almost four hundred pages long, but it doesn’t tell you that it’s about diabetic peripheral neuropathy until you get to page 19. There’s no executive summary at the beginning – in fact, there’s no title page, no contents page, no hint of what the document is even about, and it skips randomly from one sub-document to another, all scanned and bundled up in the same gigantic file.

If you’re a nerd, you might think: these files are electronic; they’re PDFs, a type of file specifically designed to make sharing electronic documents convenient. Any nerd will know that if you want to find something in an electronic document, it’s easy: you just use the ‘find’ command: type in, say, ‘peripheral neuropathy’, and your computer will find the phrase straight off. But no: unlike almost any other serious government document in the world, the PDFs from the FDA are a

series of photographs

of pages of text, rather than the text itself. This means you cannot search for a phrase. Instead, you have to go through it, searching for that phrase, laboriously, by eye.