Back of Beyond (21 page)

And then I remember Andrew and Alison Johnson’s honest island cuisine at their Scarista House hotel, where you dine on Harris crayfish, lobster, venison, salmon, or grouse (whatever is fresh that day) as the sun goes down in a blaze of scarlet and gold over the white sands of Taransay Sound. And then the two Johnnys—the brothers MacLeod—on “the first good day at the peats in nine months,” slicing the soft chocolaty peat with their irons into even-sized squares for drying. I talked with them at dusk as they moved rhythmically together along their family peat bank (their piece of “skinned earth”). “Another eight days like this should see enough for the year,” the elder Johnny remarked, still slicing. The younger Johnny nodded and eyed the whisky bottle half hidden in a nearby sack. “Not jus’ yet,” said the first Johnny. The second Johnny grunted and lifted his fifteen hundredth peat of the day.

Not far away, Dougie MacDonald was working his own peat patch, alone. His grandfather and his father had both been crofters but Dougie found little appealing in the life. “I tried it but the land was sour—there wasn’t enough anyway. Two ridiculous acres! When I was a lad it didn’t seem so bad. Don’t suppose it ever does. We always had a fine fire of thick peats. My dad would cut ’em with the others over in the bog—he was a dab hand with a tuskar, once cut a thousand peats in four hours and kept on going all day. I used to help him a bit. We’d come on back around five o’clock and tackle my mother’s ‘pieces’ (flour scones with butter) before supper. Not much meat, maybe once a week on Sunday. Breakfast was

brose

—a scooping of oatmeal with salt and milk. Salt herrings were good, though. It was mainly our own stuff—tatties, turnips, oatmeal—same as now.”

He nodded toward a pan boiling on the stove. It was full of potatoes. In the sink were more unpeeled potatoes and on the table, salt, pepper, and margarine. I saw no meat or eggs, and no refrigerator. On the wall above the table was a faded color print in a frame of a stern-faced man.

“William Edward Gladstone,” Dougie told me. “My dad called him ‘the crofter’s hero.’ Didn’t make much difference, though, in the end. Most of them had to do what I did—work for somebody else. You couldn’t do much else.”

His surly attitude reminded me of an incident that had occurred a few days previously. I’d been wandering through the Lochinver Peninsula, a wild area of Scotland forty or so miles to the east across The Minch, which separates the mainland from Lewis and Harris. I had paused for a dram of Skye malt whisky at Lochinver’s Culag bar, and someone was talking about recent discoveries in the Allt nan Vamh caves where eight-thousand-year-old human bones had been discovered. Apparently the remains of lemmings were also found, which led to the remark by a thickly bearded student, accompanied by his dog, that lemmings and crofters “had much in common.”

It had been a boisterous evening with Gaelic songs by the locals and free-flowing beer. The spirit of the Highlands was an almost tangible presence. But abruptly the mood was broken and an ominous silence spread over the room. The barman paused in the middle of pulling a pint. Someone coughed nervously. The barmaid went pale.

“I wonder,” began one of the singers, a burly man in a navy blue fisherman’s sweater, “I wonder if you’d care to repeat what you just said now.”

No one moved. The student took the bait, apparently oblivious of the mood, and began to explain his thesis that Highland crofters brought about their own destruction by refusing to cooperate with the landowners in modernizing the marginal economy of the region.

“They were stubborn—bloody minded,” he said. “They wanted their own patch of land and that was all. They didn’t consider changing, most of them. They wouldn’t listen, even when it was proved they’d never last another generation—they’d all starve. They just went ahead and destroyed themselves.”

A moment’s silence was followed by a thunderous uproar as a dozen men bellowed out rebuttals, and the student began to realize what was happening. The barmaid had vanished. Even the dog began to look uncertainly at his master. People began moving for the door, and an old man passed me chuckling. He paused and whispered, “I’d be getting back a bit, laddie, if I were you. You’re a wee touch too close sitting there.”

He was right, and much as I would have liked to record the ensuing discussion, I decided I had a lot more traveling to do, and discretion, in this instance, was certainly the better part of valor.

“He’s opened up a real wound wi’ that one,” the old man remarked as we strolled alongside the fishing pier. He was still chuckling. “M’be there’s something in what he says. We’re sticklers for tradition in these parts, and I’m not sure that it’s got us very far really. There’s a few that carries on, but the old places are pretty much dead nowadays—it’s all holiday cottages and outsiders trying to preserve everything like it was theirs. S’not bad here yet, but south of Torridon it’s hard to find anyone who’s lived there for more’n a few years. Some only come for a few weeks a year. Rest of the time their houses are empty. Applecross is the same. They opened a road but it was too late. Most of them had gone. Now the houses are falling in or they’ve been snapped up by outsiders. Captain Wills (of the Wills tobacco family) is tryin’ some new ideas, so I’ve heard, but he’ll have a job on. Even ’round here”—he gestured at the village of Lochinver straggled along the bay in the moonlight and the fishing boats nestling against the harbor wall—“the trawlermen aren’t local, most of them come by bus from the east coast every week. They say property’s too expensive. City folk have been buying it all.”

The picture he painted sounded very bleak. I asked him how he thought it might all end and he chuckled again.

“Maybe with a few more cheeky bastards like that one,” he nodded over at the bar where the hubbub still continued. “At least it makes ’em think a bit.” His face tightened. “They’ve all got families that’ve lived ’round here for God knows how long—forever, more’n likely. If they want to stay they’ll stay. Some go off for a while and come back. Some you’ll never see again. But it goes on y’know—and they’re still around to argue about it.”

We stood on the edge of the quay. A chilly breeze blew in off the loch and wavelets clicked against the seawall. “You staying long?” he asked. I said I had no plans.

“Best way,” he murmured. “Best way.” And then, “If you’re around tomorrow I’ll show you a few places, if you’d like.” So I stayed and delayed my next journey.

It’s the only way to travel.

The Outer Hebrides left many more memories: the Sunday silences on Lewis when no buses run and everyone is “at the stones” (at church); the colors of Calum Macaulay’s tweeds produced in his weaving shed—all the tones of the lochans and the rocks and the moors captured in his sturdy cloth; Catherine Macdonald knitting her woolen cardigans and jumpers from hand-dyed island wool; the stooping winkle pickers of Leverburgh whose sacks of tiny shellfish leave the island by ferry for the tables of famous Paris restaurants; that first taste of freshboiled island crayfish; ninty-three-year-old Donald Macleod carving sheep horns into elegant handles for shepherds’ crooks; the sight of a single palm tree against the enormous lunar wilderness of Harris (the offshore Gulf Stream keeps the climate mild here).

Then I remember Derek Murray at Macleod’s tweed mill in Shawbost eyeing with pride the tweeds collected from the homes of his crofter-weavers; the strange conversations in “Ganglish”—an odd mix of Gaelic and English; the lovely lilting names of tiny islets in the Sound of Harris—Shillay, Boreray, Coppay, Berneray, Tahay, Ensay, Pabbay; the huge Blackface rams on the machair land with their triple-curl horns; the gritty and occasionally grim Calvinist protestantism of Lewis compared with the Catholic-Celtic levity of the Uist and Barra islanders in the southern part of the chain.

Finally I remember that Hebridean light—sparkling off the turquoise bays, crisping the edges of the ancient standing stones of Callanish on a lonely plateau overlooking Loch Roag, making all the colors vibrant with its intensity and luminosity, making the place just the way I knew it would be….

Magic.

SCOTLAND—TORRIDON

A peat fire glowed in the hearth and my cup of tea steamed. “He’ll be back in a while.” Mrs. MacNally adjusted the crochet cover on the little afternoon tea table and eyed the plate of shortcake. “Now go on, help yourself to another. He won’t be long at all.”

It was warm and cozy in the study of the old farmhouse. There were books everywhere, piled on the chairs by the door, on the desk, spilling out of Heinz Beans cartons in the corner by the potted plants.

“He loves his books,” she whispered.

Outside the wind howled through the pines, a broody huddle of trees in this treeless place. Clouds were moving fast; the surface of the Loch Torridon was leaden gray most of the way across to the crofts of Annat. Sudden shafts of sunlight struck the water and burst into silver shards, shimmering for a moment, then disappearing. Seagulls were silhouetted black and moving inland.

“It’ll be a storm tonight. Look at the sheep.”

Across the salt marshes I could see them snuggled together in the hollows of old grass-covered dunes.

“They always know. Much better than barometers.”

A mahogany clock ticked on the mantelpiece. My wet boots steamed along with the tea in the reassuring warmth of the peats. I felt utterly comfortable in the small room surrounded by all these books and framed photographs of eagles, foxes, and badgers. I reached for another piece of shortcake.

“He’s coming.”

There was just the sound of the wind. I followed Mrs. MacNally through the hall and outside to the gravelly track that linked the farm to the valley road. Way in the distance I saw the Land-Rover, splashing through puddles and banging over the ruts with the single-mindedness of a tank.

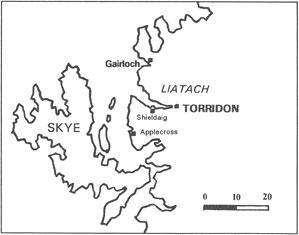

Suddenly I felt tiny. The tight human scale of the house where I’d arrived after hours of boggy hiking was gone, and I was staring once again into one of the wildest landscapes of Scotland—the high “empty lands” of Torridon. Straight ahead the seven summits of Liathach rose almost vertically from the cleft of Glen Torridon to shiny quartzite domes that gave them the appearance of perpetual ice cover. Behind Liathach was the gray bulk of Beinn Eighe, the razor ridge of Creag Dhubh and, far beyond, the solitary giant of Slioch towering over Loch Maree.

Few outsiders come to this part of the country. It’s far too remote and difficult a region for the casual traveler. The weather is notoriously fickle; the great peaks often vanish for days on end in sluggardly sea frets; infrequent “blue days” quickly turn black in sudden mountain storms. Walkers have vanished forever in the peat bogs behind the mountains, out beyond the Pass of the Winds.

Here are some of the world’s oldest rocks displayed in clear Grand Canyon sequence from the six-hundred-million-year-old quartzite caps through the pink sandstone strata to the more than two-billion-year-old-Lewisian gneiss bedrock. One wonders at the original height and bulk of these monoliths, but millions of years of earth movements, erosion, and glaciation have failed to erase their impact as you emerge from the lower peaks of Glen Shieldaig Forest, turn east at Shieldaig village, and come face to face with them across Loch Torridon. You feel you’ve entered some secret world here. As a child I remember catching a glimpse of their white summits on a ferryboat from Skye. They appeared briefly through sea mists, flashed in the sun, and vanished again. No one else on the boat saw them, and I later wondered if I’d imagined the moment. But now finally I’d come back and found that they were just as real and magnificent as I’d hoped.

“He’s here.” The mud-splattered Land-Rover came to a halt near the windbreak of pines, and Mrs. MacNally grinned like a young girl. “Late as usual.”

It’s hard to think of Lea MacNally doing anything “usual.”

I first heard his name by chance as I chatted with Donald MacDonald at the general store in Fasag village on the north side of Loch Torridon.

“Lea’s a real man of the land. He’s the National Trust warden here and knows every nook and crevice and every bit of bog around Beinn Eighe. He’s a very canny man, keeps to himself—a pretty wild one too in his younger days. They say he’d outfox any keeper they put out there. He knows all the tricks of the red deer. He thinks like a deer—knows where to find them and what they’ll do next. If you’re walking up around here, talk to Lea first. And listen to what he tells you. If it wasn’t for Lea there’d be no more reds left in Torridon now. He’s the one that keeps them alive—an old poacher fighting off the poachers! He’s the Deerman. That’s what we call him.”

So now there were two cups of tea and two pairs of steaming feet in front of the peat fire. Lea gazed quietly at the glow. He’d been out on the moors for more than twelve hours, and his small wiry frame was almost lost in the cushions and folds of the big armchair.

“Y’see,” he began slowly, “the one thing you’ve got to understand is that these creatures—all the mountain animals—everything’s against them. It’s not just your poachers and suchlike. It’s the little things you don’t even think about—wire fences, plastic bottles, broken glass, even a backpack thrown away. Deer comes up, gets the straps tangled round its antlers and mouth—starves to death. Sometimes the things I see—the way they’ve died—it makes you want to weep.”

He paused. “Come and look at this.”

We left the cozy room and walked down the hall to the old dairy. “I’m making this into a museum of sorts. It’ll not be finished yet awhile.”

Lea turned on the light and I gasped. The place was a charnel house of skulls, bones, and antlers, scores of them, all carefully labeled.

“Most of these creatures died because of someone’s carelessness.” Stark photographs told the stories: a huge stag choked to death on an iron tent peg; another tangled in barbed wire; two “knobbers” (young deer) torn apart by an unleashed dog, another whose jaw had been smashed by a weekend-hunter’s bullet, leaving it unable to eat or drink….

“These hills teach—or at least they should teach—respect. First of all respect for yourself because this is some of the toughest walking-climbing country in Britain. But respect too for the creatures who live here—the deer, foxes, badgers, eagles, wildcats. This is one of the last places you’ll find them. Most other habitats have been wiped out long ago. By the time everyone starts to get all upset it’s too late—they’ve gone. And they’ll never come back. All we’ve got left are photographs and cranks like me prattling on about preservation and suchlike….”

Our conversation carried on well into the night and over the long slow days that followed as I roamed the high hills here and began to see life in a new, quieter way. I put aside plans for my great hike across the Torridon wilderness for a while and instead sat quietly among the great golden surges of gorse and broom, watching and listening.

“A deer can smell you half a mile away even on a calm day,” Lea had told me. “But we’ve got senses we never use. We can smell animals too. Its hard at first but if you give yourself time…”

I saw rare ptarmigan in the lower rubbly hills, among the glacial boulders, suddenly rise up like a snow squall. I watched a fox “mousing” on tiptoes with its back arched like a cat, trailing a rabbit. I saw skeins of geese and whooper swans heading south in great fall migrations across the tundra landscapes of Mulcach. One warm evening I watched a young buzzard practicing divebomb attacks on clumps of tufted grass. Grasping its “prey” it soared a hundred feet, dropped it, and then caught it again before it hit the ground.

I saw woodcocks and grouse so well camouflaged in the burned browns of autumn bracken that you could almost step on them without noticing. I watched the cruel ways of the hoodiebird, a pernicious scavenger and attacker of weak creatures, always going for the eyes of its victim first and then slaughtering slowly with cool dispassion.

I heard but never saw the lonely wildcat. She was out one night hunting near my tent; something alarmed her and the dark was cracked open by her terrifying scream and hiss. The following morning I saw paw marks leading to a narrow gap in a scree pile and the remains of the two tiny voles outside her den.

It was the height of the red deer rutting season, but they were far too cunning and elusive for me. They stayed well back in the wilderness, beyond the waterfalls of Allt a Bhealaich; occasionally I would spot a small herd moving like wispy shadows across the umber grasses of the bogs. In the evenings the clack of horns in the ritual male duels and the bellows of the stags would echo down the high valley of Coire Dubh Mor.

Eagles were always around. At first they were wary of me, but after a while they ignored my flailings among the heather. One actually saved my life. It was a misty day high on the quartz flanks of Laithach. The morning had been clear and bright and I set off climbing the steep sides of the mountain with every intent of being back in Annat for afternoon tea at the Earl of Lovelace’s Torridon House Hotel. But I’d forgotten the fickleness of the Scottish climate. With no warning at all, a sea fret moved in off Loch Torridon, wrapping the mountains in a clammy gray fog.

I decided to sit it out, but after half an hour or so I was wet and impatient. So I began the descent as best I could, trying to memorize my route around the eastern flank of the mountain. The fog became thicker and colder. My inner voice warned me to find a hollow and wait till it passed, but stupidly I kept on going. Then out of nowhere came a shriek, a cracking of twigs, and a flurry of brown wings. Ahead of me a huge golden eagle reared up from its eyrie, its hard eyes staring right at me, its crooked beak open and tallons outstretched. I slipped and fell hard on the quartzite; the eagle shrieked again and soared off into the fog. I could feel the rush of air from its wings.

My legs were useless, they’d gone to putty. I felt nauseous and pulled myself into a crack in the rock as far from the nest as I could. I stayed there for what seemed like hours until the fog finally lifted. Then I could see the eyrie quite plainly, a three-foot-high pile of twigs and bark perched among rocks on the edge of a vertical drop that ended four hundred feet below in a splay of dark scree. If the nest hadn’t been occupied, if the eagle hadn’t shrieked, I’d have walked right off the edge into foggy oblivion.

After that little escapade Lea joined me on some of my rambles. “You’re not really ready yet,” he told me when I described my planned hike across Torridon. “Wait a few days. Watch the creatures with me.” And how he loved the creatures of Beinn Eighe—

his

territory,

his

creatures,

his

lifework to protect them as best he could and yet to respect their wild, spontaneous spirits.

We wandered over the low rubbly hills littered with glacial boulders. “Can you imagine the ice,” he said, pointing to the ancient gouged valleys, “hundreds—thousands—of feet thick, great white ice cliffs high as Beinn Eighe?”

He told me hard, cruel tales of the old days when the hills were the home of wild rustlers. “Way back of Liathach there’s the Pass of the Dividing—a cold place, that—they once killed one of their women there. She stole an ox liver before they divided the meat, tried to hide it under her shawl. That’s one of the best bits of an ox. They chased her, stripped her, sliced her head off, and struck it on a pole in the pass. They say it was there for a good quarter century or so—screaming in the nights. Gory stuff. Hills are full of these tales. Amazing anyone goes out after dark!”

Lea is responsible for organizing the annual culls of deer to keep the herds from becoming overpopulated and underfed in the long winter months. “I do it because I know they’d starve if I didn’t. Twelve stags and thirty-five hinds—sixteen percent of the herds. But I don’t enjoy it. And I don’t always like the people we get on the culls either.” He described the art of “still-stalking,” where you have to crawl on your belly sometimes for miles through marsh and nettles and spiky gorse. He used a polite phrase: “On a cull you’re very much at the mercy of the capabilities of the guests.”

“Which means?” I said.

“Well—some are not as fit as you’d like them to be.”