Back of Beyond (11 page)

At last—Cap Haitien. An active and colorful port city of narrow streets lined with Spanish-style stucco buildings, all couched in a bowl of jungly hills. A large white cathedral with a prominent dome sat at one side of a shady plaza.

Here I played the hedonistic tourist for a while, splashing in my hotel pool set on a steep bluff overlooking the town and harbor, eating elegant five-course dinners while a Haitian band played out-of-tune folksongs.

King Henri Christophe, one of the first rulers of Haiti after its fiery independence in 1804, chose this area for his regal headquarters and had an enormous Versailles-style palace built at Milot, about twenty miles east of Cap Haitien, where he entertained his court and foreign admirers with all the elegance and extravagance of French royalty.

He had great dreams for his new nation and formed a fitting model for Eugene O’Neill’s

Emperor Jones

. “Haiti and the Haitians were born to glory,” he reputedly stated, “to greatness, to life, to immortality.” He forgot to emphasize though that such glory would only be won by keeping the poor Haitians working as virtual slaves in the old colonial plantations and sacrificing the lives of twenty thousand of his countrymen in building one of the largest fortresses in the world—Citadelle La Ferrière—on a mountain peak, high above his palace, as a bastion against any neocolonial invasions by Napoleon or others.

His suicide in 1820, at a time of peasant rebellions, began Haiti’s long tradition of errant leaders, most of whom have been violently disposed of by a populace still seeking its own “glory and immortality.”

Standing among the crumbling rooms and terraces of Christophe’s palace ruins and looking down on the tiny shanties and patchwork of gardens and sugarcane fields far below, I let the contrasting images of this strange little country flash by: a nation of artists in love with vibrant color and form; a nation of enormous inequities between the peasant farmers and the “mountain monarchs” in their mansions and walled compounds high above Port-au-Prince; the explosions of flamboyants, bougainvillea, and hibiscus against deforested and eroding hills; the power and energy of country voodoo ceremonies against the slovenliness and sloth of city “bidonville” slums; the fiery souls of peasants, haunted for generations by the “specter of the master,” hidden under a surface patina of smiles, laughter, and laissez-faire lethargy.

“Deye mon, gen mon”—“Behind the mountains, there are mountains”—goes the saying. And it’s true. The enigmas endure. Haiti is still mystery, complexity—and pure adventure.

COSTA RICA

Iceland—ah, Iceland!

A vast, treeless terrain filled with all the teeming folklore figments of the wild Viking imagination—a place of boyhood fantasies—a place to roam across wind-scoured wastes, scaling glaciers, wandering the great ice dome of Vatnajökull.

“Sorry, sir. Iceland is closed.”

Two days before departure and the nice lady from the national tourist office calls to tell me that there’s been a general strike. All flights are canceled.

So here I am with a free week between Major Commitments and nowhere to go.

I trust my travel agent implicitly. He and I have worked our way through many sticky schedules, and when he suggested Costa Rica I thought, what the heck, it’ll be fun to go somewhere I know nothing about.

“Central America? You gotta be out of your mind. That whole place is nothing but bananas, guerilla wars, and loony drug-dealing dictators!” Friends can be like that—very bigoted in a protective kind of way.

My travel agent held fast. “Costa Rica is different from anywhere you’ve ever been—it’s one of the most peaceful and lovely places on earth. Trust me.”

Florida flashed by from thirty-six thousand feet—miles of empty sunburned scrub with occasional rococo swirlings of subdivisions scratched in the dry earth and no houses on them (I bet the fancy brochures make them look like bits of paradise). Mexico was much the same color without the subdivisions; occasional wrigglings of mountain ranges gave the martini-mellowed passengers some startling landscapes to look at. Guatemala was on fire. Thousands of tiny slash-and-burn

milpas

were clearing virgin jungle for peasant farmers (deforestation chomping through the mountains like King Kong at a wedding breakfast).

Honduras came as a surrealist pause in the middle of endless plains of banana trees; a ramshackle airport littered with sinister, slouching police; snoozing staff who forgot to fuel the plane, and one terrified native who tried to make a dash for somewhere across the runway and was dragged off by soldiers in green fatigues bristling with grenades and automatic weapons. Nicaragua was invisible—not an acre of that war-torn place could be seen through the gray haze.

Then came Costa Rica, sparkling-clear with vistas of open-mouthed volcanoes along the cordilleras and a marshmallow-soft landing at San José in the middle of the cool central valley. I felt like a kid with a Christmas stocking full of unopened presents.

The presents came brightly wrapped, intense little moments on my first day in the capital of a million or so inhabitants. Comfortably settled in the delightfully old-fashioned Gran Hotel (with casino!), in a room overlooking the main square, I flung back the tall windows and found a miniature version of the Paris Opera House facing me, the Teatro Nacional. A Verdi opera was advertised for that night to be followed in a couple of days by a group of Central American folksingers notorious for their left-wing views on everything from bananas to bombs. It was my first introduction to the democratic verve of this tiny nation of 2.5 million people.

Directly below me, street vendors sold replicas of black-clay Indian whistles, flowers, string hammocks, and mini-mountains of fresh fruit to couples strolling by hand-in-hand. Cicadas buzzed furiously in the shade trees. There were lovers everywhere—smooching, hugging, whispering and swooning into each other’s eyes. (“Making love is the number one pastime in Costa Rica,” I had read somewhere.)

It was the evening rush hour. Traffic snarled and honked all the way down Avenida Central; elegantly coiffured ladies jay-walked, jiggling slim hips in tight skirts, a neon temperature sign flashed 75° (it’s always 75° in San José); inelegant tower blocks rose into the brilliant blue sky behind a jumble of smaller stucco buildings adorned with shutters and pantile roofs. And beyond all this were the soaring cones of the great volcanoes, Irazú, Poas, and Barva, whose occasional irritable shrugs and burps are a reminder to the Costa Ricans, better known as “Ticos,” of the tenacity of life in their capital.

“Our volcanoes give one a distinctly existential perspective.” Ticos can be very eloquent, at least around San José, and in Guillermo Santamaria I had obviously met one of the more loquacious examples at the hotel café on the square. “When Irazú blew in 1963 she covered most of the city and our valley with

ceniza

[ash] day after day for months. It was terrible. Thick fog all the time.”

Guillermo drank his tiny cup of black coffee with three fingers extended like porcupine quills. When he first introduced himself I expected some sell-job of a touristy nature. Now it was obvious he merely wanted to talk.

He continued. “And poor Cartago [a colonial city ten miles east of San José], almost completely destroyed in 1841, then again in 1910, then half-buried in ceniza in 1963.” He sighed a long Latin sigh. “So sad. It was such a beautiful city.”

A policeman walked by with dark glasses and a big revolver, high on his hip. I made some inane remark about Central American dictators and their impressive armies.

“Army!” Guillermo spluttered over his coffee, sprinkling a little on his crisp white shirt. “We have no army in Costa Rica. You, my friend, are ensconced in an oasis of peace here. Truly. Our colleagues to the north and south have their problems, many problems—El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Panama—but we’ve had peace here since 1948. That’s forty years with no revolutions, no dictators, and no army, thanks to “Don Pepe” Figueres Ferrer. He brought us democracy, free elections, and free education and medicine. He helped peasants to own their own land, he even established a ‘University of Peace,’ which is still here today. And you know about Oscar Arias Sanchez…” He couldn’t resist a little jab, “You have heard of our president, Arias? Well, he is now

trying

to bring peace to all of Central America. He is a good man, a brilliant man, but—such a task! Our country is surrounded by…” He thought better of explicit epithets. “Momentico.”

He raised his three spiny fingers again and a waiter appeared immediately.

“Dos quaros.”

The drinks arrived in tiny glasses. We toasted Arias with the harsh clear liquor, distilled from sugarcane. Two more arrived.

“I welcome you to Costa Rica,” he said slowly, “and I trust you will discover and enjoy our very special and very real peace.”

After a third round of quaros, peace was taking on a very tangible quality on my first evening in Tico-land.

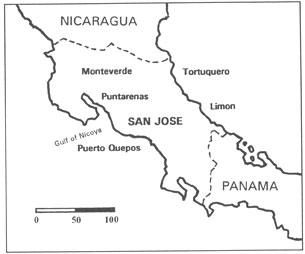

Costa Rica really is a tiny country, about half the size of Virginia, but that in no way detracts from the amazing diversity of topography and nature. From the “land of eternal spring” at four thousand feet in the high central valley, the topography falls steeply on both sides, fifty miles to the humid Pacific Coast and sixty miles to the even more moist Caribbean. Toward the northern border with Nicaragua, beyond Lake Arenal, is the arid Guanacaste, a mysterious empty region with ancient ties to the Maya and Olmec cultures; in the south, toward the Panama border, are the still-unexplored ranges of the Cordillera de Talamanca and the torrid tropics of Golfo Dulce and the Peninsula de Osa.

There are over eight hundred species of birds here (more than all of the United States and Canada combined); eight thousand plant species (with over twelve hundred different types of orchids); twenty national parks and reserves covering almost ten percent of the nation; the world’s finest “high-acid” coffee and sweetest bananas; three symphony orchestras; twice as many teachers as policemen.

Columbus was right when he sailed along the Caribbean side of the country in 1502 and named it Costa Rica, “the rich coast.” Typically, of course, his idea of riches referred more to the possibilities inherent in the gold ornaments worn by the coastal Indians than the natural fecundity of the country. King Ferdinand’s early Spanish colonizers were sadly disappointed by the lack of significant gold sources and the aggressiveness of the natives. Settlement was sparse and half-hearted even after the establishment of Cartago as the capital in 1563. The Spanish felt abandoned and adopted native lifeways (while still managing to decimate the native population); Costa Rica was too poor and too far from the center of Spain’s Central American empire in Guatemala to be of lasting interest.

Following independence in 1821, the undeveloped country was ripe for domination by avaricious visionaries. On my second night in San José I attended a powerfully satirical production in one of the city’s many underground theaters. The young cast presented a musical synopsis of the nation’s history, highlighted by the theme song “Quien Soy?” (“Who Am I?”). The tight-packed audience constantly broke into spasms of laughter, tears, and jeers (how the Ticos

love

their theater!) as the troupe of eight acted out the arrogance of the nineteenth-century coffee barons, the empire-building antics of the American pirate, William Walker, and the machinations of Boston’s Minor Keith who supervised the construction of the incredible 104-mile-long San José-to-Limón coffee railroad in the 1880s (a most unusual jungle ride experience for adventurous travelers).

Keith went on to found the notorious United Fruit Company (La Yunai) on 800,000 acres of free banana land in the eastern coastal plain. Even the gradual emergence of democracy here, following the demise of those larger-than-life intruders, was marred by occasional oppressive dictatorships, and it was only (as Guillermo had proudly told me) the unifying gift of Pepe Figueres that ultimately brought social reform and peace to this battered land. When the final chorus of “Quien Soy?” came, the audience rose as one and surged to the stage, embracing the players, some openly weeping, shouting slogans of pride for the peace and democracy of their little nation. That night they knew exactly who they were.

After two days of museums and remarkably active nightlife in San José, I was ready for sun, sand, and the simple life. So I rented a car and drove the winding road down from the high central valley, through mile after mile of coffee plantations, to the languorous seaside town of Puntarenas on the Pacific Ocean.

Doe-eyed Brahma cattle lolled about in the moist green fields of the coastal plain, attended by their retinues of white egrets. Most of the peasant homes were simple, colorful clapboard structures with tin roofs, hidden in profusions of palms and banana trees.

At Puntarenas I left the land behind and sailed off on a small launch across the Gulf of Nicoya, into a hazy blue-on-blue limbo. Pelicans perched on quano-coated islets, occasionally dive-bombing the waves for snacks. Cormorants skimmed like shadows, low over the swell.

The mainland was soon lost in warm mists and we eased among islands, dozens of them, into hideaway-heaven. Most of them had a few fishermen’s homes on them, simple driftwood shacks shaded by coconut palms, looking out over strips of pure white sand. The boats were often nothing more than hollowed-out tree trunks; nut-colored children splashed in the surf, waving. Behind the beaches the jungle rose up in a tangle of vines, covering high rocky hills.

A few islands were free of inhabitants, lovely lonely places where you could live out beachcomber fantasies among the butterflies and orchids, eating the always-abundant wild fruits, fishing whenever the mood was right, and generally bidding farewell to the fripperies of the high-tech life for as long as it took to touch and know again the things that really matter.

You lose track of time out here. The haze, the moist heat, and the gentle rolling of the boat move you into a different reality; the endless yammer of the mind ceases as you drift from one island to the next and the next, watching the greens move back into the blues, and on through shimmering silver to a gold so soft and translucent you feel you’re disappearing into a Turner landscape of pure light….

The next day I drove south from Puntarenas down the Pacific coast, through the hot and funky little town of Puerto Quepos, deep into the jungle wonderland of the Manuel Antonio National Park.

I stayed in a small cabin high on a hillside overlooking arcs of white beach and turquoise ocean. While the park was not as remote as the Nicoya islands, I still managed to find my own stretch of pristine sand here, snorkeling the day away, climbing up through the dense clammy jungle on Cathedral Point for even more spectacular vistas of cliffs and ocean. I shared the walk with hundreds of scarlet-and-black land crabs who live in little burrows among the roots and have a frustrating disdain for photographers.

Closer to the beach, I was joined by statuesque iguanas who exhibited just the opposite reaction and spent most of their time posturing their prehistoric profiles like movie star has-beens. One rather large three-foot-long male became incensed when I took portraits of his female companions but ignored him. So he followed me fifty yards along the beach until I finally succumbed to his persistence, then swaggered back to his harem, brandishing his sharp spines pompously.

Around eight o’clock the following morning I knew something had gone decidedly wrong. My mouth was dry and then full of saliva, then dry again. My body sweated like a bilge pump, streams of it, and the day’s heat hadn’t really hit yet. My simple cabin was still cool.

I had to get to the bathroom—fast. And then again. And again. By midday I’d spent most of my time there and, so far as I could tell, I had nothing more in my body to expunge. But still I sat. Waves of nausea flowed over me, sending hot and cold ripples up my spine. The mirror on the wall showed a deathly face edged in a moldy-green sheen and eyes so tired and egglike that I began to wonder if survival was in the cards at all.

Hour after hour passed. Time twisted in cobra coils; my brain wandered around its confines like an inebriated slug. Crazy thoughts kept popping up—utter free association. I was definitely in the throes of some emerging fever. All energy had long since been dissipated.

I moved to the bed and twisted and turmoiled. Occasional shards of sound came from outside: the surf, gulls, someone passing my cabin. The sounds became a series of symphonic variations, sometimes so distorted that I couldn’t recollect what the original sound was as my brain now became a freewheeling bagatelle. The voices of passing children reverberated like Buddhist bells and gongs—booming, peeling, cymbaling into switchbacking roller coasters of sound.