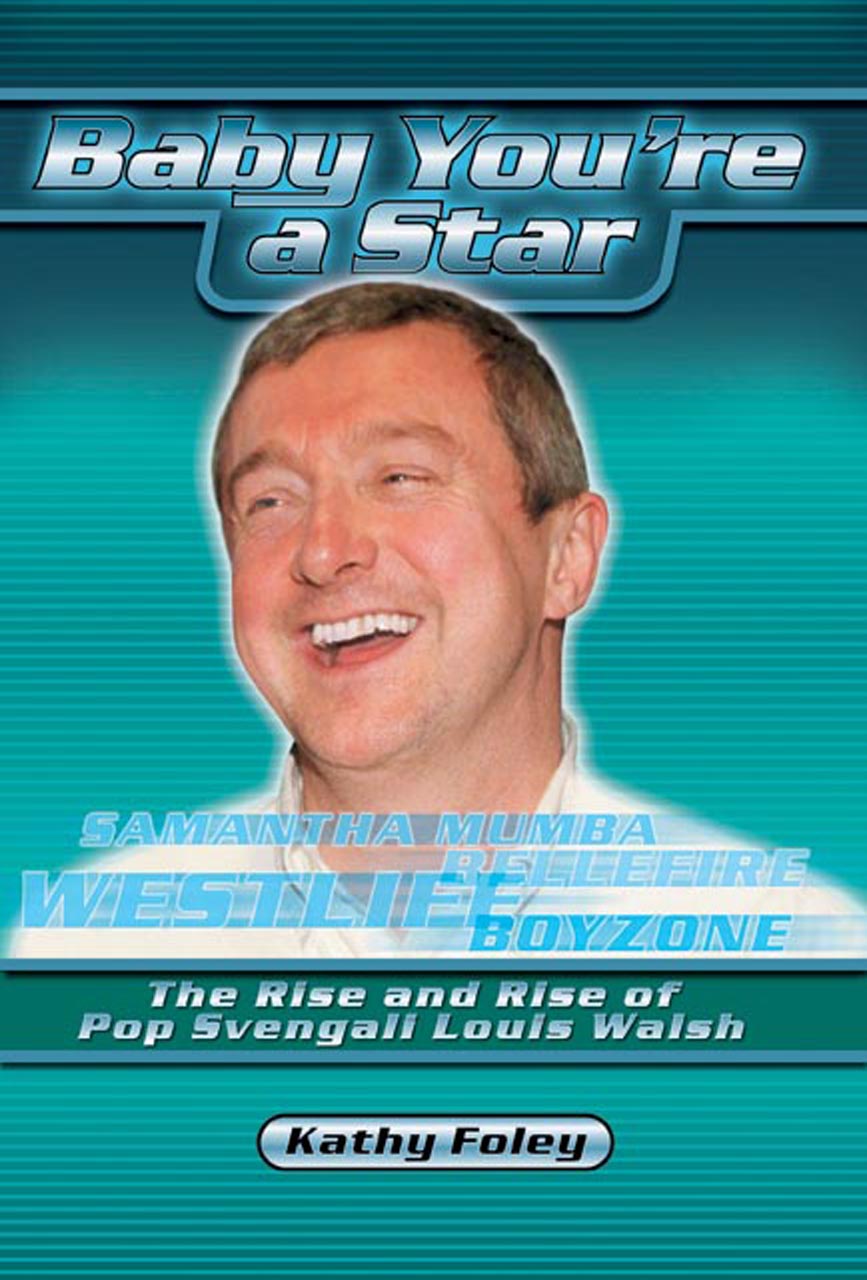

Baby You're a Star

Read Baby You're a Star Online

Authors: Kathy Foley

Baby You’re a Star

The Rise and Rise of Pop Svengali, Louis Walsh

by Kathy Foley

-PROLOGUE-

POP SVENGALI

Pop: ‘music of general appeal’

Svengali: ‘one who exerts a malign persuasiveness on another’

For any young wannabe pop star in Ireland, Louis Walsh is the way, the truth, and the light. He is Mr. Pop, the Pop King, the venerated god of Irish pop. He has guided his selected protégés to 22 No. 1 singles and six No. 1 albums in the UK, and many more No. 1s across Europe and Asia. He steered Samantha Mumba to No. 1 in the US, something few Irish or British pop managers have succeeded in doing. In short, he is Ireland's one and only pop svengali.

Svengali is a word often used to describe music managers at the pinnacle of their powers. Svengalis are the manager-gurus, the best of the best, those who are remembered along with the acts they managed. There was Brian Epstein and the Beatles, Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin, and Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols. Modern-day svengalis include Paul McGuinness, the manager of U2; Simon Fuller, the manager of the Spice Girls; Lou Pearlman, the former manager of the Backstreet Boys and 'N Sync; and of course, Louis Walsh, the manager of almost every successful pop act to emerge from Ireland.

The original Svengali was a character in George du Maurier's successful novel

Trilby

, published in 1894. Svengali was a Hungarian hypnotist and singing master, who transformed a young French girl named Trilby into Europe's leading soprano, and lived in luxury on the proceeds of her concerts. The word “svengali” slipped into everyday use to mean a person who moulds others into musical sensations. The word in its original form was negative. Svengali's character was cruel and evil; he used his influence to mould his young protégée into a captivating singer, and ex-ploited her for his own gain. Thus the dictionary definition of svengali as "one who exerts a malign persuasiveness on another".

With the passing of time, the word has altered in con-notation and interpretation. Modern-day svengalis no longer exercise a malign influence on their protégés; they act as their guardians, guiding them through turbulence and difficulty. They still need to be per-suasive and influential, however.

Pop svengalis like Louis Walsh are rare commodities. As with any profession, there are music managers who are mediocre, vast numbers who get the job done, and a select few who excel.

James Fisher, general secretary of the artist managers industry body, the Music Managers Forum (MMF), has a theory on this. To really succeed, he says, managers like Louis Walsh must be "single-minded and bloody-minded".

"Successful managers are fairly bloodsome [sic]," according to Fisher. "They're fairly difficult, because they've got to fight all the time. They've got to be very sure of their ground. You can't be woolly as an artist-manager. Even if you make the wrong decision, which you'll do, you've got to make decisions."

Band managers are not like managers in other industries. They don't sit in enormous leather swivel chairs smoking cigars and deciding which golf course they'll play on next. Band managers must stay close and involved with their artists, constantly advising and guiding them. Although there might be hundreds of people working with a successful band, from producers to stylists to merchandisers, the manager is the one person responsible for ensuring the entire structure doesn't collapse around his protégés. Louis Walsh has a natural born ability in this regard.

"When you think about it, the manager is the one person in the music industry that has to know everything; everything that his artist needs to do to be a success," says Fisher. "Every area in the industry involves the artist, from publishing to copyright law to record shops. The manager has to know about contract law to do with contracts for his artists. They always have lawyers and business advisers, of course, but he has to wade through that and represent his artist in those negotiations. He has got to know about the charts and how they work. He's got to understand about insurance because every time the artist goes on tour with equipment or every time it rains in the middle of a gig, he's got to be able to understand all that and know how it goes. He's got to understand about merchandising. It really is endless."

So endless, in fact, that the list of Louis Walsh's responsibilities doesn't stop there. "He needs to be an amateur psychiatrist, he really does. Artists are not always straightforward people and somebody has to talk them through their problems and troubles, so he has to understand personalities . . . and personality disorders, come to that."

While Fisher's list of a manager's responsibilities might seem exhaustive, it isn't. According to

The MMF Guide to Professional Band Management

, the official bible of music management, pop managers also have to be capable of dealing with agents, accountants, backing musicians, producers, promoters, publicists, publishers, record company executives, songwriters, sound engineers, tour managers, video directors, and any number of assistants trailing around after each of those people.

Niall Stokes, founder and editor of

Hot Press,

Ireland's leading music magazine, believes Louis always had the necessary qualities to be a successful music manager. "What he brought to the party was an obsessive love of music, an ability to inveigle people into doing things or taking a chance, a certain kind of canniness, which was an important factor for people involved in the showband scene, and an instinct for what would travel, would sell. And obviously that's a fairly substantial set of assets to set out with."

Simon Napier-Bell, former manager of Wham, Japan, and the Yardbirds among others, and author of several books on the music industry,

You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

(1982) and

Black Vinyl, White Powder

(2001), says Louis has reached the prime position in the music industry by simply finding "successful artists". He repeats the words without elaboration. He doesn't attribute the success of Louis’ career as a pop svengali to anything else.

Well-known record producer Pete Waterman believes his Irish friend and business associate is driven by his love of pop music. "That sounds an obvious qualification but it is sadly lacking in most of the managers. Many of the managers today don't care about the music. They only care about the business and doing a great deal. There're a lot of guys love the deal, but don't love the music. To them, they might as well be selling carrots or bars of soap. They don't care who they're dealing with, and don't get too close to their artists or their problems."

While music critics often frown at the mention of Waterman's name and dismiss the sort of music he produces as itself no more exciting than carrots or bars of soap, his pedigree as a pop svengali can't be ignored. He has been a DJ, a record producer, a promoter, a song-writer, and a manager. He has worked with most forms of popular music from reggae to disco, and dealt with a staggering range of acts. He has also been, and still is, involved with many of Louis Walsh's acts. Waterman is a huge fan of Louis Walsh and his style of management. He attributes Louis’ meteoric rise in the music industry to old-fashioned values.

"Louis Walsh is a typical example of an old-fashioned manager," opines Waterman. "I use that in a complimentary way, not in a derisory way; he's old-fashioned. He still allows his heart to rule his head and he's still more interested in the hit than making a bob. He'll make a bob but it's more important for Louis to have the hit. He'll sacrifice a lot for that hit, which is what a good manager should always do. It's old-fashioned in this day and age. Some don't give a shit about anything but how much money they can plausibly get out of it, which is why, of course, managers don't last five minutes. The minute their act isn't successful, they're gone, they're doing something else."

The fact that most pop band managers "don't last five minutes" is not just because they're obsessed with money. It's because they think they can follow the pop band formula, but they don't have the golden touch, the nous to make it happen, that special svengali quality. Louis Walsh has such a straight-forward style that many believe it is easy to emulate but there is no simple formula for pop success. To a large extent, he is misunderstood by both his critics and those who desperately want to become his protégés.

To be a pop svengali, you have to be hard-working and determined, dedicated and committed. You have to be charming and good at dealing with people. You have to be single-minded and capable of making tough decisions. You have to be able to cope with unending abuse and condescension from the critics, and an unerring talent for self-publicity certainly won't go astray. Somewhere deep inside, you have to have a hunger for power and wealth and fame. Above all else, you need a genuine love of music and a desire to make hits.

"Nobody that makes hits is admired anywhere. We've all got leprosy because we're populists," says Waterman. "We entertain the masses. Certainly for the last 20 years, it has been unacceptable socially to be populist. Everybody tries to be trendy. Well, Louis Walsh and people like him, will never be trendy ever, because unless the audience is applauding, we don't play. Critics being nice about you is smashing but we'd rather take the applause in the auditorium. Record sales are a nice bonus but the money is not what we do it for; it's the applause."

1

FROM KILTIMAGH TO DUBLIN

Louis Walsh has always considered his life outside work a private affair and the business of no one but his immediate family and those he loves. He has always done his utmost to keep his personal life to himself, apart from providing slight details about his youth during interviews. To date, there have been dozens of articles and profiles written about his life and career, but these have rarely separated the truth from the myth. He is a man shrouded in celebrity, yet he manages to evade any media intrusion.

The true story of Louis Walsh begins in the west of Ireland. Michael Louis Vincent Walsh was born on 9 August 1952 in Kiltimagh, a village situated in the heart of Mayo, a poverty-stricken county decimated by emigration since the Irish Famine of the 1840s. He was named after his father, Michael Francis, a solid man known to his friends as Frank. Louis inherited his enduring work ethic from his father, a man who worked hard and provided well for his family. From his mother Mary Catherine, known to everyone as Maureen, Louis received his unerring determination and self-belief.

The Walsh family lived on Chapel Street, the continuation of Kiltimagh’s Main Street. When Louis was born, his parents already had a young daughter called Evelyn. The family was to grow considerably in the following years, with the addition of another daughter, Sarah, and six more sons: Paul, Frankie, Eamonn, Padraig, Joseph and Noel.

These days, Kiltimagh is a pretty and pleasant place to visit. The houses are gaily painted in bright pinks, greens, yellows, reds, and blues. There is a sculpture park, a museum, and retreats where artists can work.

In 1952 life was different. The village was located in part of Mayo’s notorious Black Triangle, a remote hinterland where good agricultural land was scarce, and industry non-existent. East Mayo did not even get electricity until the late 1950s.

Times were hard, but Frank and Maureen Walsh did everything possible to give their children a good upbringing. Louis says his parents were “just honest hard-working people that got on very well and looked after all the kids, and that’s all they ever wanted.” When Louis was a child, Frank Walsh worked as a hackney driver and ran a small farm adjoining the town. Louis often had to help out on the farm but he never enjoyed it. The work was gruelling and as the family had no farm machinery, everything had to be done by hand.

His father was a quiet but authoritative figure, who never drank and held traditional values. It was an era when people worked hard to make ends meet, and raised their children to be well-mannered, polite to their neighbours, and respectful to the Catholic Church.

Louis’ mother was a sociable woman who loved music and learning, and adored her children. She was particularly fond of her eldest son, who took after her in every way. “Louis was more like my mother than my father,” says his brother, Frank Walsh. “She was probably the dominant person in the family.”

Maureen Walsh acknowledges that Louis resembles her physically, but modesty prevents her from taking credit for his seemingly unending determination.

Both Louis’ parents came from East Mayo, so the children had dozens of relations living nearby. “The front door,” says Frank Walsh, “was always open. It was never locked at all. There were always loads of people in and out of the house. Of course, my father was a hackney driver as well, and there would always be people coming in and out looking for lifts here and lifts there,” he said.

When Louis was a young child, his father’s mother also lived in the house. “She adored the ground he walked on and he loved her too. They called her Muddy, and she was a lovely lady. She adored him and he was so fond of her. He was so upset the night she died. He must have been about 12,” remembers Maureen Walsh.

Although Louis’ parents provided him with proper guidance and discipline, they did not have the means to indulge their children extravagantly. The Walsh family was working class. As in most farming families of the time, the children made do with what they had and never realised the family was not materially well off. “We didn’t know”, says Louis and smiles. “I thought we were having a fantastic time.”

As the family home was a small end-of-terrace house, the children had to share both bedrooms and beds.

“There used to be three of us in the bed, and I used to have to be in the middle,” recalls Frank Walsh. “I always remember on a hot night, you could be trying to toss and turn, and someone would give you a kick.”

In spite of their straitened circumstances, the Walsh children were happy and content, although Louis, in particular, could be mischievous at times.

One of his brother Frank’s earliest memories is of Louis showing him how to earn money. “He used to have myself and my brother out hunting for old glass Cidona bottles, the big flagons, and the Lucozade bottles. We would gather them from the highways and byways and you could get money back on them in the shop,” he recalls.

Louis’ business acumen was already blossoming and he instructed his younger brothers to do the hard work, cutting their fingers on briars and bushes fishing bottles out of ditches and fields, while he took charge of the enterprise. “He would take the lion’s share,” remembers Frank Walsh. Louis already enjoyed the thrill of earning his own money.

With so many children in the Walsh house, it was always a loud and lively place. It is difficult to imagine the influences that shaped Louis’ life and encouraged him on a career path into the music industry. His parent’s example was certainly a major contributing factor. “We were a very musical house. His father was very musical and was a very good singer,” says his mother.

“I haven’t a note in my head at all, but I come from a musical family. My father was very into music. The love of music was on both sides of the family. When he was a child, he was very quiet but very into music from a very young age. It was all he wanted to do, was listen to music, even when he was very small,” she says.

Maureen Walsh’s favourite singer was Nashville star Jim Reeves, but his father preferred musicals. Louis constantly listened to his parent’s musical collection on a record player given by his aunt to his father.

“I can still see it. My Aunt Anne bought it for my father when he was very sick and there were like 12 albums,

My Fair Lady, Carousel, Mario Lanza,

that type of music. It was great to have a record player then, and we used to buy 45’s in Castlebar,” Louis says.

Music became his drug. Music drove Louis to distraction, and he would do whatever was necessary to start collecting his own records. “I used to go into Castlebar and buy one or two. I would nick them now and again as well,” he admits.

As a child who loved music so avidly, he was also glued to the radio whenever possible. He would tune it to 208 medium-wave, or as the resident DJs called it, “Radio Luxembourg – Your Station of the Stars”.

Sunday nights were a particular favourite, when Jimmy Saville and Barry Aldiss played the week’s top 20 hits. He was an avid reader of

Spotlight

, the top Irish pop music magazine of the day, and pored over articles about all his favourite stars. When there was no music playing at home, Louis would go across the street to a neighbour’s house and sit in on the rehearsals of a local band.

Around this time, Ireland was undergoing a seismic social and cultural change. In comparison to the drab and dour 1950s, the 1960s were a whirlwind of music, dancing, and romance. As a young child, Louis was captivated by what became known as the showband era. He was young, impressionable and like all young boys, craved heroes and a sense of individuality. Louis’ heroes were singers and musicians.

“One of the first records I bought was definitely

The Hucklebuck

,” he says. “Evelyn and myself; we used to dance to that in our house at home. I bought the Rolling Stones. I remember buying

Here Comes The Night

and

Let’s Get Together

by Hayley Mills. And there was a Beach Boys song called

Do It Again

.

“We used to swap records down the town with different people. 45’s were the big thing. They were 7/6d then or something, which was a lot of money for a poor family in Mayo.”

Louis attended Kiltimagh Boys National School. He was a bright child who displayed an irreverence for authority and who always had something to say. His brother Frank remembers him making a wise crack at a bishop’s expense; something his parents and con-temporaries wouldn’t dream of even considering.

“When the Bishop was coming around to check out the schools for Confirmation, there happened to be some-body in the class, who said they didn’t believe in God. Louis puts his hand up and said, ‘Don’t be daft’.” The story sounds implausible but is absolutely true.

When he completed his primary education, he was sent to St. Nathy’s boarding school in Ballaghaderreen, Co. Roscommon to begin his secondary education. He was 11 years old.

St. Nathy’s was an imposing institution that had originally been a British military barracks. The school itself had produced large numbers of priests and several bishops, which is partly why Maureen Walsh decided to send him there. She privately harboured ambitions that Louis might devote himself to the Catholic Church. He had already served as an altar boy in the local church for some years, and the family had an amicable relationship with the local clerics in the Kiltimagh parish.

If Maureen Walsh hoped her son would join the priesthood, she was mistaken. Louis hated the school. He had no intention of devoting his life to religion. He couldn’t fathom why his mother expected him to enter the priesthood and take a vow of celibacy.

“My mother thought, at one stage, I might be a priest. I have no idea why. I hated the place,” says Louis. “I didn’t like arithmetic and geography and Latin and all that. I liked science and I liked English. It was absolutely dreadful.”

Academia was lost on Louis. He was not the studious type. He resented the formality of boarding school, and did not enjoy obeying orders or bowing to ultimatums. It was a joyless time for him. Louis didn’t complain about the school but accepted his predicament. But his experiences there left him depressed. His parents didn’t realise how much he hated the school until he failed his first set of exams. He could find no way of fitting in, no matter how much he tried.

“I didn’t realise for about a year. We always thought, ‘Oh, he’ll settle. He’ll get used to it’ but he didn’t really,” says his mother. In truth, Louis’ mother had no other option but to send him to St. Nathy’s. The reason was simple and obvious, as she explains: “You couldn’t do your Leaving Certificate in Kiltimagh at that time.”

But he used his time at St. Nathys to learn hard lessons about life. Reminiscing on this period, he says: “Going to boarding school . . . the food was horrible. If I had kids, I don’t think I would send them to boarding school. It’s like being on religious retreat all the time. I wasn’t lonely, but there was no music, there was no television – the things I like. There was no good food, there was nothing. It was either Gaelic football or studying, and I had no interest in either; none at all. But I think it was good for me in one sense because it prepared me for the big bad world.”

Although he was probably far brighter and more astute than he realised, he did not succeed academ-ically. He failed to pass his Intermediate Certificate, the compulsory national exam for 15 year-olds. After that experience, his mother decided not to send any of her children to St. Nathy’s. Louis eventually completed his education at St. Patrick’s College in Swinford, nine miles from his home in Kiltimagh.

Of St. Nathy’s, he says, “I left the school because I failed almost everything in my Inter Cert. They advised my mother not to send me back. I wasn’t expelled. So I went to day school in Swinford. That was great fun, because I used to go down on the bus every day, having a great laugh, great fun and I got my Leaving Cert.”

Louis Walsh was different from his school contem-poraries in many respects. Along with having no interest in his studies, he was also uninterested in many of the passions shared by his school friends. He disliked Gaelic football, the bedrock of local life. Louis, though, had a passion of his own – pop music. He possessed an uncanny ability to remember tunes and lyrics of songs, countless songs. There was scarcely a style of popular music with which he wasn’t familiar.

“All I ever wanted to do was work somehow in music. To be a DJ, or work in a radio station, or an advertising agency, or a magazine. I just wanted to work in entertainment,” he says. For a youngster growing up in rural Ireland, the bright lights of show business were nothing but a far off dream. But Louis possessed both a sincere love of music and great determination, and few traits could have served him better in his ambitions to succeed in the music industry.

Pop music mesmerised Louis. He thrived on it. Music afforded him the opportunity to escape the frustration of small-town life in rural Ireland. More than anything, he wanted to be part of the music scene. At the age of 15, he got his first break.

“When I started going to St. Patrick’s, I had lots of free time. I was going home every day and I wasn’t studying. So I started booking this local band, a local three-piece. They were like Status Quo. They were called Time Machine.”

Louis’ career in the music business had begun. Soon he set about persuading more prominent band managers to give Time Machine supporting roles at concerts. As there was no telephone in the Walsh household on Chapel Street, Louis organised his fledgling business using the local phone box. He would wait anxiously outside the public telephone in Kiltimagh village until he heard it ring. He was dogged in his pursuit of securing support slots for his act.

“I used to use the local public phone box to get through to promoters like Oliver Barry, Jim Hand or Jim Aiken. They were based in Dublin. They used to give Time Machine support slots to the big showbands.”

The promoters rarely met their schoolboy business associate. Instead they knew Louis by name only and were impressed by his conscientious and professional approach to his small business. Few realised how young he was because he spoke authoritatively. From Louis’ perspective, this was the essence of his success. He had unlimited energy and a clever wit, which allowed him to pass himself off as someone more experienced.