B004YENES8 EBOK (39 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

Mace’s lawsuit did come to fruition. To defend me I hired my friend and the previous year’s California Trial Lawyer of the Year recipient, Marshal Morgan. He readily agreed to handle this case that he deemed a “slam dunk.” There were early storm warnings on this lawsuit, first from my then-new business manager, Jess Morgan (no relation to lawyer Marshal Morgan). We were not, he relayed, getting billings of any size from Marshal’s law firm. I attributed this to my very friendly relationship with Marshal, but Jess was more than skeptical; to him, no billings meant no work was being done.

Then there was the unofficial call from Mr. Neufeld’s attorney asking my pal and sometime lawyer, Sam Perlmutter, if—since Mace was not really “after Barney”— I would be willing to join his client in the law

suit against Orion and kick in $25,000 toward attorney’s fees? Sam thought it interesting enough to pass along; my response was quick and vituperative. “I wouldn’t give that asshole twenty-five cents! Tell him to go fuck himself.”

Barbara took off from work to attend the trial on a daily basis. Mace, of course, was also there, always in the company of his hand-holding spouse, Helen. The idea that it had probably been at least twenty years since either of these two had actually held hands anywhere was noted by this storyteller along with the observation that the normally natty Mr. Neufeld was attending each day of the two full weeks of trial seemingly in the same suit, which looked as if it came off some low-end department store rack. The Neufelds, it seemed from this seat in the bleachers, were in full performance for the jury.

Neufeld’s lawyers finally rested, and the judge had us all break for lunch before hearing from the defense. It was late morning on a Friday; Loeb & Loeb (the Orion lawyers), along with Marshal and me, made a beeline for the nearest coffee shop. The two lawyers were debating whether to even present a defense. They felt that Mace had not made his case and that all they had to do was ask for a summary judgment; Neufeld’s claim would be thrown out, they speculated, and that would be it. By presenting a defense, they maintained, we couldn’t possibly be any better off and just might “step in something.”

I interjected. “Fellas, I know very little about the law, but I know something about audiences, and let me tell you what I believe that jury (our audience) has heard and what they didn’t hear. They didn’t hear that the plaintiff, the guy in the $100 suit, has ‘his’ and ‘her’ Rolls Royces in his Beverly Hills garage, and a two million dollar African art collection in the attached mansion where he lives when he is not flying his private plane.

“They didn’t hear,” I went on, “just how much of his net worth has been ‘earned’ by this selfsame, ongoing sort of litigious behavior against any number of former associates, and I am not so sure they understand that his whole involvement in this project is a legal fiction, or that I only took additional fees when Orion’s business affairs department sold me on their judgment that what was being done was not only perfectly legal but, for all I knew, might have come about as some sort of a tit-for-tat arrangement between Mace and Medavoy to which I wasn’t privy.

“You guys,” I continued, “might be right technically, you might be right legally, but if this testimony isn’t heard and it is up to that jury, we are dead meat.”

Both sets of lawyers were convinced I was wrong. I would not overrule the venerable men of Loeb & Loeb or my own counsel, despite my growing belief during the trial that Marshal was winging this whole thing. The lawyers’ plan was followed; no defense was presented. The motion for summary judgment was carefully listened to by the judge, and, as I watched his body language, I began to be convinced that my team was right after all. Then, just (I believed) on the verge of deciding to rid his courtroom of all of us, to end the thing right there, the old guy in the robes spoke. “I think the jury, which has been here for nine days hearing this case, should have the opportunity to make the decision here.”

Marshal leaned over to me. “No problem,” he said. “We’re in great shape. It’s Friday afternoon, and this jury is gonna want to get out of here in time to beat the traffic. This will be over in an hour.”

He was wrong by two and a half days. The following Tuesday afternoon the jury found for Mace Neufeld against Orion Pictures Corporation and its codefendant, Barney Rosenzweig. My part of the judgment was $1,300,000.

A meeting was held between all the combatants in the judge’s chambers; the defense attorneys pleaded for a lessening of the amount awarded. The judge wasn’t having that. The guy from Loeb & Loeb then surprised me, asking that, at the very least, the judge let Mr. Rosenzweig out of this as, at worst, he was truly an innocent bystander who could have no idea what Orion might or might not be paying Neufeld in the deal that precipitated this lawsuit. The judge wouldn’t allow that either.

I was referred to a top-notch law firm in San Francisco that specialized in appellate work. I learned no new evidence could be put forward in an appeal and no new testimony. The Lawyer’s task would be to find, within the context of what was already on the record (by having been presented in court) where an error had been made and then to show that it would be unjust if that error were not corrected by this appeal process.

The San Francisco lawyers were not so sure they could be effective doing that but would try the case against their better judgment for a whole lot of money. The case they wanted, after reading all the transcripts, was the malpractice suit they said I should file against my friend, attorney Marshal Morgan. I couldn’t bring myself to follow that advice.

I had been paid a lot of money by Orion, a few million in advances against my ownership position. Now Mace had been awarded a large share of that: $1,300,000. One problem was I didn’t have the millions that had been paid on those advances; it hadn’t been spent exactly, it had been expensed out to my

partners

: 10 percent to the William Morris Agency, 5 percent to my business managers, and 50 percent of what remained, as part of the community property settlement, to my ex-wife, Barbara Corday.

I went to each of them for their share of the judgment. The Morris office squealed; Jess didn’t like it at all (he never believed Marshal was doing the work and might have asked for better counsel if he knew he, too, was at risk). Barbara wasn’t at all happy with this request either.

This money was received by me after Mace’s lawsuit had been filed. The aforementioned threesome wanted their share as soon as it came in—even though it should have been clear to all that there was a cloud on the horizon. It had to be acknowledged that they all knew—no matter how remote the chance—that Neufeld might prevail. I did not hold the money back against the trial date or place it in escrow; I paid it out to them. Now that we lost at trial, it was time that all returned that proportionate share of the monies they had received in order to satisfy the judgment.

Each finally came through ($130,000 from the Morris men, $65,000 from Jess Morgan’s company, $455,000 from Corday).

Chapter 44

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

Author-barrister John Mortimer admonishes his readers never to learn to swim. His reasoning for spurning this aquatic skill is that while sailing, should one capsize, there might be the temptation, if one were a swimmer, to strike out for the shore and, invariably, drown. “Better,” he says, “to cling to the wreckage” and await rescue.

That is what I did and, in very short order, came up with the CBS series

The Trials of Rosie O’Neill

, as well as

Christy

, along with four

Cagney & Lacey

reunion movies. This was all made possible by the firing/resignation of Kim LeMasters and the ascension to power at the network of Jeff Sagansky.

Sagansky was my kind of executive. Unlike LeMasters, who I felt had a need to prove he was the smartest man in the room (and, indeed, the only human being I have ever met who actually had read Machiavelli’s

The Prince

), Jeff Sagansky believed in hiring good people and letting them do what it was they were being paid to do. That is not to say he didn’t occasionally get into micromanaging a script, and he was plenty smart and good at it as well; but when he did, it was somehow acceptable (at least to me) because his method was steeped in boyish enthusiasm. He has an infectious charm about him.

Jeff was supportive, not competitive, but for me, as a storyteller, dealing with a buyer who would always be my most important audience, the quintessential difference between Sagansky and LeMasters was that the former understood what the latter seemingly could not—or would not: That the fundamental synergy between the two opposing forces of the storyteller and his audience (in this case the seller and the buyer) is the willingness and ability to suspend disbelief.

There are only lights and shadows on that screen. The audience must bring something to the party; that essential “thing” is the willingness to sit back and be entertained, to be disarmed. My perception was that Kim LeMasters simply would not do that and that he had to prove—at a script meeting or a screening—that he was smarter. To do that he had to keep his faculties very alert, never letting down his guard or allowing himself to be seduced. The gal from

The Arabian Nights

would have been boiled in oil long before Ali Baba met those more than three dozen thieves if LeMasters had been her captor.

I remember a particular note-taking session, following a screening for LeMasters. His comments were precise and, the argument could be made, technically correct. However, to effectuate what he was asking would have—

in my opinion

—damaged the larger issues of the film itself.

“There are twenty-four frames per second

88

that run through a projection machine in order for us to perceive natural human-like movement on the screen,” I began my part of the LeMasters meet. “I have read where a highly intelligent individual can, by concentrating very hard, actually perceive the lines been each and every frame.” The reference to the capability of a highly intelligent individual had, I thought, captured LeMasters’ attention. “It’s possible,” I paused for effect, “but, Kim—why would you want to do that?” I gave him a bit more on the willingness to suspend disbelief and then added, “Y’know, if you are looking for mistakes, there are twenty-four per second.” Sagansky might smile gleefully at this point, but not LeMasters—at least not in my experience. It was Sagansky who wanted to revisit

Cagney & Lacey

via the reunion movie format. I had never wanted to do this in the five-plus years that had passed since those bygone days on the series. By then, Sharon and I were married.

89

Tyne (now post-Broadway and starring for me in the CBS series

Christy

) was very much a close friend of us both. There was never a doubt that I could deliver the two women to the roles they had made famous. I had other reasons for not pitching this as something I wanted to do. First off, I had no desire to make Mace—or Orion—richer. Secondly, I wasn’t at all sure that we should compromise the memories people had of our show. We would revisit this terrain, I reasoned, at our peril, for we would not only be compared with other movies on TV, but with memory—and a memory that had probably received some coloration that would be difficult, or impossible, to live up to with any new incarnation.

I told Sagansky I would think about it, but not all that much. The movie-for television business was an OK business, but not my specialty. My forte was series television, and one could make a whole lot more money in that arena than in the TV movie field. Then it occurred to me that I might be able to eat my cake and have it as well.

I went to Orion with the proposition that I would make these movies (at least two—for that was my minimum guarantee from Sagansky) on the condition that Orion would sell me the

Cagney & Lacey

library: all 125 episodes, plus the original Loretta Swit film.

Len White was now Orion’s president during their period of then-recently announced bankruptcy; he was caretaker over what he hoped would be a takeover (or sale) of the entire company—including their fairly substantial library of films and some TV shows.

My theory was that I could use these yet-to-be-made movies as the locomotive that would pull the train: the collection that was my erstwhile series. White was sympathetic to my emotional attachment to the show, happy to have some action, plus the possibility of an influx of some dollars, which—at least—might justify some of his salary and expenses.

The price he would have me pay for the right to make the movies was an outrageous $250,000 per film, way too high for rights on any movie-for-television of the time. But that figure would, he added, be applicable to my overall purchase of the entire series library, the price of which he set at $6,000,000. It was a lot of money for a series that had already had the sprocket holes run off of it and had been handled badly in the field to boot. There was also the fact that I didn’t have six million dollars. That didn’t matter so much if you subscribed to the Jerry Weintraub philosophy that “If you live long enough, you cannot overpay for a film library.”

Canal Plus, the French TV and film distribution company, was prepared to front the six million on my behalf. Betsy Frank, then of the Saatchi & Saatchi advertising agency in New York and always a big

Cagney & Lacey

fan, indicated there might be millions available from one of her clients, if the women would be available for product identification ads. I was ready to cut Sharon and Tyne in on this new action and was confident I could deliver them for that kind of campaign.

A tiny wrinkle in the deal was that President White did not want it perceived as a sale or as someone cherry-picking the Orion library. This, therefore, had to be presented as a partnership between myself and Orion, with the latter receiving 10 percent of the profits. White needed this, he said, for appearances and told me he never expected there would be any profits. Clearly he had experience with bookkeeping in the film and television business and assumed my guys would keep books the same as his guys.

Unfortunately, “my guys” are scrupulously honest, and the current holders of this copyright regularly receive profit distributions from the movies while there have never been any on the series itself coming to me from the other side. (Whoever said “What goes around, comes around” clearly has never been in my end of show business.)

In order to effectuate the purchase, a phase of “due diligence” was begun. I went on, preparing to make the two

Cagney & Lacey

films back-to-back that late spring and summer in Los Angeles. Steve Brown & Terry Louise Fisher were set to write both scripts. James Frawley would direct the first; Reza Badiyi would helm the second. My youngest daughter, Torrie, was the associate producer; my middle daughter, Allyn, would serve as costumer; my oldest, Erika, as well as niece, Bridget, would both have small acting roles; and my son-in-law David Handman was one of our film editors. It was like old home week.

(The films were individually called

Cagney & Lacey: The Return

and

Cagney & Lacey : Together Again

, but collectively—along with the two other reunion films we would eventually make—were all lovingly known as

Cagney & Lacey: The Menopause Years

.)

I told Steve and Terry we should treat the six intervening years since our series had ended as if our fictional characters had continued to have a life during that time and to establish this early, as we had all those years before, with the Lacey baby quinella. Both Sharon and Tyne had aged and put on some weight in the process, and so we would play that.

90

Lacey would have taken her retirement, and a menopausal Cagney would have been promoted to the district attorney’s office and—since series’ end—gotten married!

Sharon hated this idea and not even the casting of old pal and

Tony

Award – winning actor James Naughton in the role of her husband would change her view. I stuck to my guns, as I hoped the marriage would give us some stuff to work with and show some growth or change in our characters.

The argument over this is barely worth mentioning, but, in fairness to my spouse, I will admit for the record that fan reaction to the marriage was (at best) mixed to negative.

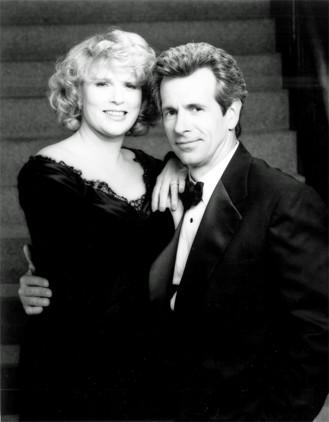

Tony Award– winning actor James Naughton, as the man who would be married to Christine Cagney in the first of our reunion films and then be divorced by her in the second. This portrait was on display at their home for the reunion party scene that took place in the early going of

Cagney & Lacey: The Return

. This twosome had met and costarred at Universal Studios in the early 1970s in

Faraday and Company

along with Dan Dailey and Geraldine Brooks.

© CBS Broadcasting Inc. Cliff Lipson/CBS

A happy reunion of the cast for our first reunion movie,

Cagney & Lacey: The Return

. Terrace is on the set of the fictional Cagney NY Park Avenue manse. Front row, from left: Al Waxman, Ms. Gless and Ms. Daly, John Karlen, and, in the rear, Robert Hegyes, Merry Clayton, Marty Kove, and Paul Mantee. Carl Lumbly was (somewhat reluctantly) in the film and in this sequence but somehow did not get into this shot.

© CBS Broadcasting Inc. Cliff Lipson/CBS