Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

B0041VYHGW EBOK (157 page)

Cels and drawings are photographed, but an animator can work without a camera as well. He or she can draw directly on the film, scratch on it, and attach flat objects to it. Stan Brakhage taped moths’ wings to film stock in order to create

Mothlight.

The innovative animator Norman McLaren made

Blinkety Blank

by engraving the images frame by frame, using knives, needles, and razor blades

(

10.93

).

10.93 A nearly abstract but recognizable bird etched directly into the black emulsion in

Blinkety Blank.

Another type of animation that works with two-dimensional images involves

cut-outs.

Sometimes filmmakers make flat puppets with movable joints. Lotte Reiniger specialized in lighting her cut-outs in silhouette to create delicate, intricate fairy tales, as in

10.94

. Animators can also manipulate cut-out images frame by frame to create moving collages; Frank Mouris’s exuberant

Frank Film

presents a flickering dance of popular-culture imagery

(

10.95

).

A very simple form of cutout animation involves combining flat shapes of paper or other materials to create pictures or patterns. The rudimentary shapes and unshaded colors of

South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut

(as well as the television series from which it derives) flaunt deliberately crude cut-out animation.

10.94

The Adventures of Prince Achmed

(1926), the first feature-length animated film.

10.95 Household objects perform comic dances in

Frank Film.

Three-dimensional objects can also be shifted and twisted frame by frame to create apparent movement. Animation of objects falls into three closely related categories: clay, model, and pixillation.

Clay animation,

often termed

claymation,

sometimes actually does involve modeling clay. But more often, Plasticine is used, since it is less messy and is available in a wider range of colors. Sculptors create objects and characters of Plasticine, and the animator then presses the flexible material to change it slightly between exposures.

“You don’t very often see model animation which is well lit, do you? For me, that’s part of the comedy of it; I love the idea that you’re making a thriller and it all looks authentic, but the lead character is in fact a Plasticine penguin.”

— Nick Park, animator,

The Wrong Trousers

Although clay animation has been used occasionally since the early years of the 20th century, it has grown enormously in popularity since the mid-1970s. Nick Park’s

Creature Comforts

parodies the talking-heads documentary by creating droll interviews with the inhabitants of a zoo. His “Wallace and Gromit” series (

A Grand Day Out, The Wrong Trousers, A Close Shave, Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,

and

A Matter of Loaf and Death

) and

Chicken Run

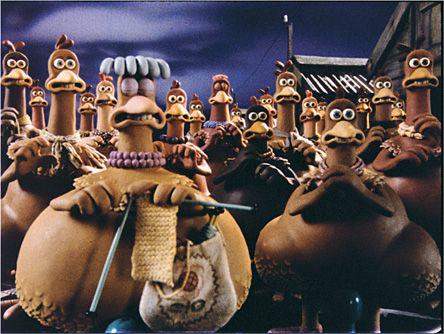

(co-directed with Peter Lord;

10.96

) contain extraordinarily complex lighting and camera movement.

10.96 A flock of Plasticine hens in

Chicken Run

receive Hollywood-style lighting.

Model

or

puppet animation

is often very similar to clay animation. As the name implies, it involves the use of figures that can be moved, using bendable wires or joints. Historically, the master of this form of animation was Ladislav Starevich, who as early as 1910 baffled Russian audiences with realistic insect models acting out human dramas and comedies. Starevich’s puppets display intricate movements and detailed facial expressions (4.85). Some of the main characters in his films had up to 150 separate interchangeable faces to render different expressions. Perhaps the most famous animated puppet was the star of the original 1933 version of

King Kong,

a small, bendable gorilla doll. If you watch

King Kong

closely, you can see the gorilla’s fur rippling—the traces of the animator’s fingers touching it as he shifted the puppet between exposures. One of the most famous feature-length puppet films of recent years is Tim Burton’s

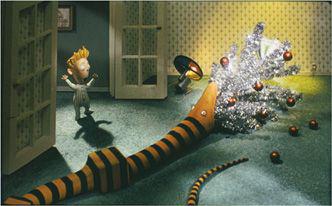

The Nightmare Before Christmas

(

10.97

).

10.97 In

The Nightmare Before Christmas,

an attempt to combine Halloween and Christmas ends disastrously.

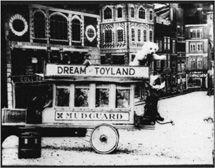

Pixillation

is a term applied to frame-by-frame movement of people and ordinary objects. For example, in 1908, Arthur Melbourne-Cooper animated toys in a miniature set to create dense layers of movement in

Dreams of Toyland

(

10.98

).

Although actors ordinarily move freely and are filmed in real time, occasionally an animator pixillates them. That is, the actor freezes in a pose for the exposure of one frame, then moves slightly and freezes again for another frame, and so on. The result is a jerky, unnatural motion quite different from ordinary acting. The innovative animator Norman McLaren uses this approach to tell the story of a feud in

Neighbors

and to show a man struggling to tame a rebellious piece of furniture in

A Chairy Tale.

Dave Borthwick’s

The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb

animates a tiny Plasticine figure of Tom as well as eerie giants played by real actors. (The humans are pixillated even in scenes without Tom.)

10.98 Animated toys in

Dreams of Toyland.

Computer imaging

has revolutionized animation. On a mundane level, the computer can perform the repetitive task of making the many slightly altered images needed to give a sense of movement. On a creative level, software can be devised that enables filmmakers to create images of things that could not be filmed in the real world.

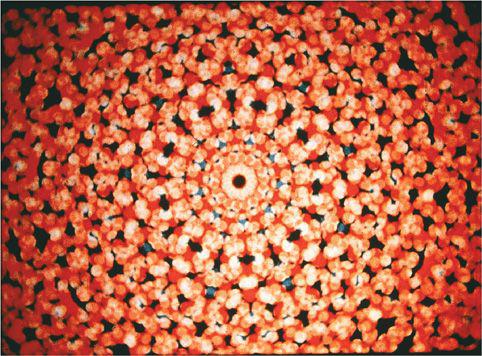

The earliest computer animation depended on intensive hand labor and could not create convincing three-dimensional compositions. James Whitney used ananalog computer to generate the elaborate and precise abstract patterns for his

Lapis

(1963–1966), but he still had to hand-prick cards to create the myriad dots of light for each frame

(

10.99

).

10.99 An elaborate pattern generated by a computer for

Lapis.

It was not until the 1980s that computer technology advanced far enough to be used extensively in feature production. Graphic manipulation of frame-by-frame images requires enormous amounts of computer memory, and the first feature film to include computer animation, Disney’s

TRON

(1982), contained only 15 minutes of partially computer-generated imagery out of its running length of 96 minutes. In the 1990s, George Lucas’s Industrial Light & Magic, Steve Jobs’s Pixar Animation, and other firms developed banks of powerful computers and complex programs for creating animated imagery. Images generated on computers are transferred to film either by filming directly off a high-resolution monitor or by using a laser to imprint individual pixels of the images onto each frame. In 1995, Pixar’s

Toy Story,

the first animated feature created entirely via computer, was released through Disney. It presented an illusion of a three-dimensional world peopled by figures that somewhat resembled Plasticine models

(

10.100

).

By 2000, Pixar’s programs had improved computer animation’s ability to render surface textures like fur, as demonstrated in

Monsters, Inc.