B0041VYHGW EBOK (150 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Of course, all films contain these qualities. We have seen how the lyrical beauty of the river and lake shots in

The River

functions to create parallels, and the rhythm of its musical score enhances our emotional involvement in the argument being made. But in

The River,

an abstract pattern becomes a means to an end, always subordinate to the rhetorical purposes of the film. It is not organized around abstract qualities but rather emphasizes such qualities only occasionally. In

abstract form

, the

whole

film’s system will be determined by such qualities.

“Thematic interpretation comes from literature: it’s been carried over to conventional narrative films, but it shouldn’t be grafted onto experimental films, which are often a reaction against such conventions.”

— J. J. Murphy, experimental filmmaker

Abstract films are often organized in a way that we might call

theme and variations.

This term usually applies to music, where a melody or other type of motif is introduced, and then a series of different versions of that same melody follows—often with such extreme differences of key and rhythm that the original melody becomes difficult to recognize. An abstract film’s form may work in a similar fashion. An introductory section will typically show us the kinds of relationships the film will use as its basic material. Then other segments will go on to present similar kinds of relationships but with changes. The changes may be slight, depending on our noticing that the similarities are still greater than the differences. But abstract films also usually depend on building up greater and greater differences from the introductory material. Thus we may find considerable contrast coming into the film, and sudden differences can help us to sense when a new segment has started. If the film’s formal organization has been created with care, the similarities and differences will not be random. There will be some underlying principle that runs through the film.

The theme-and-variations principle is clearly evident in J. J. Murphy’s

Print Generation.

Murphy selected 60 shots from home movies, then rephotographed them over and over on a contact printer. Each succeeding duplication lost photographic quality, until the final images became unrecognizable.

Print Generation

repeats the footage 25 times, starting with the most abstract images and moving to the most recognizable ones. Then the process is reversed, and the images gradually move back toward abstraction

(

10.53

,

10.54

).

On the sound track, the progression is exactly the opposite. Murphy rerecorded the sound 25 times, but the film begins with the most clearly audible version. As the image clarifies, the sound deteriorates; as the image slips back into abstraction, the sound clarifies. Part of the fascination of this experimental film derives from seeing blobs and sparkles of abstract color become slowly defined as people and landscapes before passing back into abstraction. The film also teases us to discover its overall formal pattern.

10.53 Theme and variations in

Print Generation

: in earlier portions of the film, each one-second shot is more or less identifiable.

10.54 After many generations of reprinting, the same image becomes abstract, with hot highlights remaining. The color is biased toward red because that is the last layer of the emulsion to fade in rephotography.

As

Railroad Turnbridge

and

Print Generation

indicate, by calling a film’s form abstract, we do not mean that the film has no recognizable objects in it. It is true that many abstract films use pure shapes and colors, created by the filmmaker by drawing, cutting out pieces of colored paper, animating clay shapes, and the like. An alternative approach involves using real objects and isolating them from their everyday context in such a way that their abstract qualities come forward. After all, shapes, colors, rhythmic movements, and every abstract quality that the filmmaker uses exist both in nature and in human-made objects. Markings on animals, bird songs, cloud formations, and other such natural phenomena often attract us because they seem beautiful or striking—qualities similar to those that we look for in artworks. Moreover, even those objects that we create for very practical and mundane uses may have pleasing contours or textures. Chairs are made to sit on, but we will usually try to furnish our home with chairs that also look attractive to us.

Because abstract qualities are common, experimental filmmakers often start by photographing real objects. But, since the filmmakers then juxtapose the images to create relations of shape, color, and so on, the film is still using abstract organization in spite of the fact that we can recognize the object as a bird, a face, or a spoon. And, because the abstract qualities in films are shared with real objects, such films call on skills we use in everyday life. Normally, we use our ability to recognize shapes and colors in practical ways, as when we drive and have to interpret traffic signs and lights quickly. But, in watching an abstract film, we don’t need to use the shapes, colors, or repetitions that we see and hear for practical purposes. Consequently, we can notice them more fully and see relationships that we would seldom bother to look for during the practical activities of everyday life. In a film, these abstract qualities become interesting for their own sake.

This impractical interest has led some critics and viewers to think of abstract films as frivolous. Critics may call them “art for art’s sake,” since all they seem to do is present us with a series of interesting patterns. Yet in doing so, such films often make us more aware of such patterns, and we may be better able to notice them in the everyday world as well. No one who has watched

Railroad Turnbridge

can see bridges in quite the same way afterward. In talking about abstract films, we might amend the phrase to “art for life’s sake”—for such films enhance our lives as much as do the films of other formal types.

Ballet mécanique

Ballet mécanique

(“Mechanical Ballet”), one of the earliest abstract films, was also one of the most influential. It remains a highly enjoyable avant-garde film and a classic example of how mundane objects can be transformed when their abstract qualities are used as the basis for a film’s form.

Two filmmakers collaborated on

Ballet mécanique

during 1923–1924. They were Dudley Murphy, a young American journalist and aspiring film producer, and Fernand Léger, a major French painter. Léger had developed his own distinctive version of Cubism in his paintings, often using stylized machine parts. His interest in machines transferred well into the cinema, and it contributed to the central formal principles of

Ballet mécanique.

This title suggests the paradox the filmmakers employ in creating their film’s thematic material and variations. We expect a ballet to be flowing, with human dancers performing it. A classical ballet seems the opposite of a machine’s movements, yet the film creates a mechanical dance. Relatively few of the many objects we see in the film are actually machines; it mostly uses hats, faces, bottles, kitchen utensils, and the like. But through juxtaposition with machines and through visual and temporal rhythms, we are cued to see even a woman’s moving eyes and mouth as being like machine parts.

Film style plays a crucial role in most films using abstract form. In keeping with its overall formal design,

Ballet mécanique

uses film techniques to stress the geometric qualities of ordinary things. Close framing, masks, unusual camera angles, and neutral backgrounds isolate objects and emphasize their shapes and textures

(

10.55

).

The film reverses our normal expectations about the nature of movement, making objects dance and turning human action into mechanical gestures.

10.55 A horse collar in

Ballet mécanique.

We cannot segment

Ballet mécanique

by tracing its arguments or dividing it into scenes of narrative action. Rather, we must look for changes in abstract qualities being used at different points in the film. Going by this principle, we can find nine segments in

Ballet mécanique:

C. A credits sequence with a stylized, animated figure of Charlie Chaplin (“Charlot” in France) introducing the film’s title

- The introduction of the film’s rhythmic elements

- A treatment of objects viewed through prisms

- Rhythmic movements

- A comparison of people and machines

- Rhythmic movements of intertitles and pictures

- More rhythmic movements, mostly of circular objects

- Quick dances of objects

- A return to Charlot and the opening elements

Ballet mécanique

uses the theme-and-variations approach in a complex way, introducing many individual motifs in rapid succession, then bringing them back at inter vals and in different combinations. Each new segment picks up on a limited number of the abstract qualities from the previous one and plays with these for a while. The final segments use precise elements from early in the film once again, and the ending strongly echoes the opening. The film throws a great deal of material at us in a short time, and we must actively seek to make connections among motifs.

As suggested previously, the introductory portion of an abstract film usually gives us strong cues as to what we can expect to see developed later.

Ballet mécanique

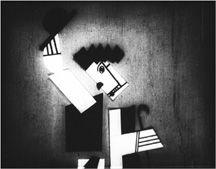

’s animated Chaplin begins this process

(

10.56

).

Already the human figure is also an object.

10.56 In

Ballet mécanique,

the figure of Chaplin is highly abstract—recognizably human but also made up of simple shapes that move in a jerky fashion.