B000U5KFIC EBOK (8 page)

Authors: Janet Lowe

Though the Munger children were sheltered from such things, there

was a resurgence of racism in America, and in 1925 the Ku Klux Klan

staged a 40,000-man parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington,

DC. Shortly before Charlie was born, there had been a mob lynching in

Omaha. The labor movement was on the rise and attempts to unionize or

picket a workplace sometimes turned brutal.' Those harsh events did not

touch the Munger children.

"In that clay and age, there was no crime at all," said Carol Estabrook.

"No drugs. We'd play outside in the evenings, games like capture the flag,

kick the can. Our neighbors put an ice-skating rink in their yard. We went

to the movies on Saturday."

By the 1930s, Omaha's exquisite Orpheum Theater had changed

from a vaudeville house to a talking-movie theater. "You had to pay as

much as a quarter to see a first-run movie there," said Charlie. "I loved all

the adventure movies, the Kipling movies, the horror movies, Frankenstein and Dracula. The first movie I remember really well was the original

King Kong. I went to it all by myself. I couldn't have been more than

eight. I think everyone in my generation who could afford it went to the

movies. I loved comedies, loved to laugh. John Anderson, my friend, had a

big, booming laugh. Once, in the Orpheum we laughed so hard that the

rest of the people in the theater started laughing just because we were."

In 1977, Berkshire Hathaway moved its annual meeting to the

Aksarben (Nebraska spelled backwards) fair grounds-familiar territory

for Munger. "I used to come here as a boy for the circus. Now we have a

circus of our own."

CHARLIE, MARY,AND CAROL MANGER all attended Dundee Elementary School

and later moved up to Central High School, which is housed in the stately

former territorial capital building. Central High was considered one of

the 25 top college preparatory schools in the country. Susan Buffett and

the Buffett children went through the same schools, though Warren did not. When his father became a congressman, Buffett finished elementary

school and attended high school in the Washington, DC area.

Buffett says he still gets letters from people who went to school with

Charlie. "Miss Kiewit was one of his elementary school teachers." She

was the sister of the well-known Omaha contractor Peter Kiewit, who

later became the first citizen of Nebraska. Miss Kiewit played the organ at

the First Presbyterian Church and was a member of Eastern Star. She had

taught for 42 years when she retired from the Omaha school system in

1970. "They had great teachers because, for other jobs, there was prejudice against women then," said Buffett. Such talented women later passed

over teaching for jobs in other professions.

The teachers of Omaha, and especially Miss Kiewit, emphasized

"thought" problems at which Munger always excelled. They also required the children to serve as crossing guards and do other chores. "Teachers

were very well-behaved people," said Munger, "good moral exemplars in the

old-fashioned sense. There was discipline. The moral teaching was good."

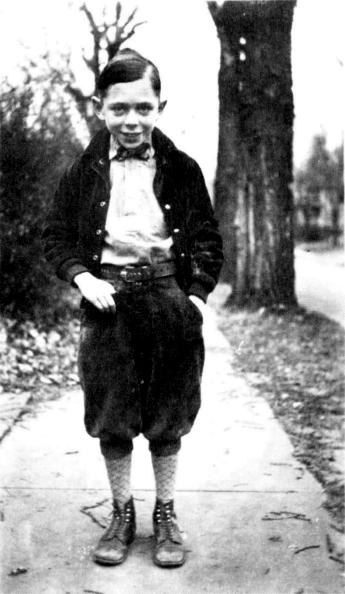

Young Charlie in knickers in Omaha.

Charlie was a star student, but he also was one of the most challenging to deal with.

"Charlie was so lively that you could hardly miss him," said

Estabrook. "He was up to something all the time. Occasionally he got in a

scrape with his teachers. He was too independent minded to bow down

to meet certain teachers' expectations. Our children are the same way.

We think it's the way to be."

Charlie also liked to tease and play tricks.

"Mother used to say, 'Charlie is both smart and smartie,' " said Willa

Davis Seemann. Mrs. Davis did her best to improve young Munger. When

he was visiting the Davis' and misbehaved, Charlie got his legs switched

right along with the Davis children.

The classroom, said Munger, was only one part of his early education. "I met the towering intellectuals in books, not in the classroom,

which is natural. I can't remember when I first read Ben Franklin. I had

Thomas Jefferson over my bed at seven or eight. My family was into all

that stuff, getting ahead through discipline, knowledge, and self-control."

Charlie, Mary, and Carol received several books each year as Christmas gifts. "We had them read by Christmas night." said Carol. "We were

very bookish people. Dad loved mysteries, Dickens and Shakespeare, biographies. Mother belonged to a book club which read everything that

was current. I remember staying at the Davies and reading medical books.

That's what the Davises had and what you read."

Despite the family's love of reading, Charlie had trouble learning to

read until his mother took it upon herself to teach him phonics. Whatever

held him back quickly disappeared, and he was soon skipped ahead in

school.

"My parents used to say, 'there were no dumb Mongers,'" recalled

Willa Seemann.

Small and slight of build all through high school, Munger grew to his

full stature of nearly 6 feet late. He was not particularly athletic, but

spent this time with books, hobbies, friends, and people he liked.

"He was always gregarious, friendly, social. He was interested in science, almost anything-he had a curious mind. Both parents had a big influence, but in different ways," explained Estabrook. "I think he related

to Dad in the business and law sense. Mother was sociable. Of course, the

Davis family was part of everybody's lives. They lived two or three blocks

away. "

The Munger and Davis families spent a lot of time together. Charlie

was between the ages of the Davis boys, Eddie and Neil. Charlie's sister

Mary was Willa's closest girlfriend.

"Anytime anything went wrong at the Munger house, they called

mother," said Willa. "Once Toody fell through the French doors. Back

then they didn't have stretchers, so they took down a door and carried her

out. Mother was a nervous eater, so she went to the kitchen and got a

sausage and an apple and ate them going to the hospital."

Like his parents, Charlie was fond of all the Davises. "Dr. Ed Davis

was my father's best friend, and I did something unusual for a person as

young as I was-five, eight, twelve, fourteen-I became a friend of my

father's friend. I got along very well with Ed Davis. We understood one

another.""

Charlie became so interested in Ed Davis and his work that "I

watched movies of his main operations and familiarized myself with surgical outcome statistics in his field."

THE PROSPERITY ENJOYED BY SO MANY AMERICANS in the 1920s came to an

abrupt end in the 1930s. By the time Charlie was six years old, the world

was in a Great Depression that lasted until after he graduated from high

school. The frightening era erupted on Black Friday, October 29, 1929.

Between October and mid-November of that year, stocks lost more than

40 percent of their total valuation, a drop of $30 billion on paper at least.

The effect was devastating to the more than 1.5 million Americans who

dabbled in the stock market, often on borrowed money. One investor,

presented with a margin account bill from her broker wailed, "How can I

loose $100,000. I never had $100,000."'

After Black Friday, the market rallied a few times, but finally floundered. Matters were made worse when a series of natural disasters deluged the United States-floods, droughts, plagues, and dust storms. More

than 40 million Americans descended into dire poverty.10

Though Munger was unaware of it, something else happened in

Omaha in 1929 that would influence his life. Warren Buffett tells the

story this way:

I'm quite fond of 1929, since that's when it all began for me. My dad was a

stock salesman at the time, and after the Crash came, in the fall, he was

afraid to call anyone-all those people who'd been burned. So he just

stayed home in the afternoons. And there wasn't television then. Soooo

... I was conceived on or about November 30, 1929, and I've forever had a

kind of warm feeling about the Crash."

Warren was born nine months later on August 30, 1930.

Tinges were so bad that every day hobos knocked on the back doors

in Omaha's better neighborhoods, offering to sweep the driveway or do

some other chore for a sandwich. "It was amazing how poor people were

in the 1930s," said Munger. "One summer it took family pull to get me a

summertime job at 40 cents per hour. And all through the depression you

could get all you could eat at Henshaw's Cafeteria, including meat and

dessert, for 25 cents."

But, said Munger, he learned some of his most important life lessons

during that time: "I had the example in early life of family members who

behaved well under stress. It must have been very hard for Grandfather

Munger to cure family financial distress that wouldn't have happened if

the suffering family members had been more like the judge. But he came

through anyway."

Both sets of grandparents did what they could to help their children

through the lean years.

"When the 1930s came Grandfather Russell, was down to very modest circumstances, his wholesale dry goods business having foundered,"

Charlie said. "uncle Ed was in real estate, and was stone cold broke and

owed money. Grampa Russell cut his house in half and moved in his

daughter and Ed-even as their oldest child died slowly of meningitis

leaving medical and hospital bills that took years to pay."

On the Munger side of the family, one of Charlie's uncles owned a

small bank in Stromsburg, Nebraska. Farmers defaulted on loans, and the

hank wasn't sound enough to reopen after Roosevelt's bank holiday in

1933. "Uncle Tom needed about $35,000 worth of good assets to replace

$35,000 of crap. Grampa Munger had $35,000 in good mortgages and put

them into his son-in-law's bank in exchange for the crap. It was a big risk.

It represented about half of his assets and there were no pensions for

judge's widows at that time. At the end of the bank holiday, Uncle Tom's

bank re-opened, and, eventually, over many years, much of the judge's investment was recovered as bad assets became merely mediocre assets."

. One of Munger's aunts had married a musician over the judge's objection. Judge Munger gave him money to go to pharmacy school, then

lent him money to buy a well-located, but bankrupt pharmacy that prospered. Both the Mungers and the Russells stuck together and pulled

through. Despite the problems the rest of the family had, Al Munger was

relatively secure.

"My father was never again so rich in real income as he was in 1936.

It was his peak of lawyering. We didn't live in a big house and have a

chauffeur, but we were very comfortable-by the standards of the day."

Al Munger's prosperity in the mid-1930s was partly clue to a law case

Al handled on behalf of a tiny soap company. Al argued that one of the

New Deal's tax laws was unconstitutional, and the case somehow got accepted for review by the U.S. Supreme Court. On the outcome swung a

huge sum of money for Colgate Palmolive Peet and a small sum for Al's

client. Colgate paid Al generously for allowing Colgate's famous New

York lawyer to argue the case, which the New York lawyer then lost. "I

could have lost it just as well for less," said Al.

Despite his family's relative prosperity in the 1930s, Charlie took

jobs when he could: "I first encountered the Buffetts when I worked at

the family grocery store. The hours were long, the pay low, opinions cast

in iron, and foolishness zero."''

Buffett & Son was started in 1869 by Warren's great-grandfather,

Sidney Buffett. When Charlie worked there, it was owned by Warren's

grandfather Ernest. The Buffett sense of humor apparently is hereditary.

Ernest's brother was named Frank.

Originally located on 13th Street, the store later moved to the western edge of Omaha, 5015 Underwood Avenue, six or seven blocks from

Munger's home.

"It was a credit and delivery store," explained Buffett. "It had a mezzanine where my grandfather would sit. Basically he was the boss. He'd

give orders. Uncle Fred, Ernest's son, did all the work."

The store had squeaky wooden floors, rotating fans, and floor-toceiling wooden shelves. When a customer wanted a can from a higher

shelf, a young clerk moved a sliding ladder to the right place and retrieved the item. Grocery boys unpacked and shelved cases of food,

cleaned out the produce bins, carried grocery bags to the homes of

Omaha matrons, and swept floors. Charlie -slaved" in the store on Saturdays. You were just goddam busy from the first hour of morning until

night," he explained.13

If Warren's older cousin, Bill Buffett, arrived late, he was greeted by

the portly, white-haired Grampa Ernest, standing above on the mezzanine

with watch in hand, "Billy, what time is it?"

Ernest Buffett was a strict employer and he held strong political

views. "He paid $2 for 12 hours of uninterrupted work. Social Security

had just been enacted, and he used to require each boy to bring two pennies to the store to pay his contribution to the system," said Charlie.''

At the end of the day, Charlie handed Ernest his two pennies and in

return received two dollar bills, plus a lecture on the evils of socialism.