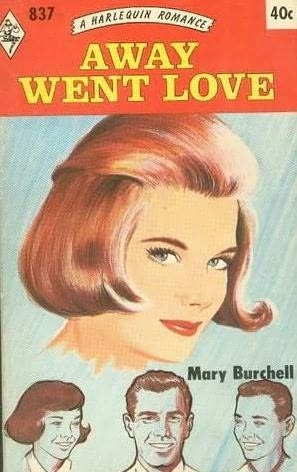

Away Went Love

AWAY WENT LOVE

Mary Burchell

The last thing Hope had ever expected was to receive a proposal from Doctor Errol Tamberly, whom she had always disliked and who made no secret of the fact that he disapproved of her.

Nevertheless, when Hope found herself forced to ask him for a loan to get her fiancé out of serious trouble, that was the only condition on which Errol would agree to help.

She had no choice but to accept, but—how would it all work out? And what possible reason could Errol have for wanting to marry her?

CHAPTER ONE

ENID FELDON looked across the tea-table at her friend and tried to think of something comforting to say. At the same time she wondered if it would seem very insensitive to take a third cake, considering that this was, after all, a visit of condolence. Still, it really was a very attractive tea—

“Do have another cake, Enid.”

Hope Arning, who had not known Enid all these years for nothing, pushed the plate invitingly nearer.

“Oh, really, I don’t know—”

Enid’s murmur lacked conviction, however, and Hope’s serious expression gave way into a momentary smile.

“Well, I do know. No one expects you to lose your appetite because someone else has just—just lost her parents.”

“But I don’t want to seem

heartless

!” Enid cried, with a fervor which sat with amusing incongruousness upon her plump charm.

“You don’t,” Hope assured her. “You just seem natural. And you don’t know, Enid, how badly I need someone or something to seem natural and familiar just now.”

Well, it was very sweet and sensible of Hope to put it that way, of course, and the cakes

were

rather special—

Enid took another one, but, as though to compensate for this faintly gross gesture, bit it with as much indifference as she could assume, considering that it had obviously been made with real butter. Then she fixed her large blue eyes on Hope with an air of sympathetic attention and spoke in that tone of synthetic brightness which we all reserve for assuring friends that circumstances which we personally consider frightful are not really as bad as they seem.

“Well, there’s one thing at least to be thankful for, Hope dear. You won’t have any financial worries.”

“Financial worries?” Hope raised her rather strongly marked eyebrows in slight surprise. “No. Of course not.”

“It’s quite a consideration, believe me,” Enid insisted, warming to her subject. “Especially with the twins to look after. Most girls of your age, left with a young brother and sister, would be at their wits’ end for money, in addition to everything else.”

“Y-yes, I know. And I’m not ungrateful for that. But I suppose it’s always a bit difficult to believe one is lucky because something

hasn’t

happened. I mean, it’s much easier to say, ‘How unlucky I am to be so hard up’ than ‘How lucky I am

not

to be hard up.’ ”

“That’s because you never have been hard up,” Enid declared with feeling. “But I know what you mean. If you’ve been lucky all your life it comes all the harder when your luck fails.”

The moment the words were out of her mouth she wondered uneasily if there were not better ways of describing the loss of both one’s parents in an aeroplane accident than as a failure of one’s luck. But fortunately Hope was very sensible and understanding and would know what she meant.

As a matter of fact, Hope was not even thinking about that part of the remark. ‘If you’ve been lucky all your life’ was the part that had arrested her attention.

Yes, she supposed, she

had

been lucky all her life until now. She had lived in a secure, happy, self-contained world which nothing had ever really shaken to its foundations.

At twenty Hope had, in addition to good looks, good health and good temper, that charming, slightly careless confidence which belongs only to those people who have never had to wonder anxiously what tomorrow will bring. Her father had not only been one of the country’s leading experimental chemists. He had also been a man with a handsome private income, which provided him with every opportunity for pursuing his own work, and his family with every opportunity for gratifying all reasonable (and even a few unreasonable) wishes.

The laboratory where Hope had worked very happily for the last two years bore her father’s name and had been largely provided out of her father’s private means. It was an open secret that, had he lived, his name would have figured in the next Honors List. And few distinguished chemists visiting the country would have considered their tour complete without a visit to the Basil Arning Laboratory.

He had been pleased when his daughter followed in his footsteps, and when Hope had wanted to go straight from school to work as a junior assistant in her father’s laboratory, the matter had been perfectly simple. She merely stepped from one sphere of pleasant security to another.

No wonder it had seemed as though the world would always go more or less as she wanted. There had been the question of Richard, of course, but even that would have solved itself when her parents came home.

And then they had not come home. They had been killed instead.

“You know, darling,” Enid interrupted her thoughts at this point. “I don’t

really

know just how it all happened—except what the newspapers said, of course, and then the newspapers never tell you what you really want to know, do they?”

Hope didn’t reply to this stricture on the press, but, oddly enough, she felt almost glad to have to tell Enid about it all. She felt too numb with shock to experience more than a dull pain in speaking about it, and in explaining to a wide-eyed Enid she might perhaps get a better grip on the situation herself.

“Why, you see”—she absently picked up her tea-cup and then set it down again without having drunk anything—“at the beginning of last month Daddy was asked to go to the States in connection with the radio branch of his work. There was a question of a big conference and, at the same time, so far as the practical side of the work—”

“You needn’t explain that bit of it, darling. I shouldn’t understand, in any case,” Enid said with great truth and accuracy. “He had to go to America because of his work. That’s quite sufficient.”

Hope smiled faintly.

“Very well, then. And this time Mother decided to go with him. He’s been—I mean he

had

been—several times during the war, of course, but in those earlier days there was no question of anyone unconnected with the work accompanying him. This was the first time Mother could go, and she was terribly excited and happy and—Well, anyway, she went.”

Enid heard the sudden flat note in Hope’s voice, and hastily thrust in a bright question to distract her thoughts.

“Just the two of them? Or was there anyone else with them?”

“Doctor Tamberly—Errol Tamberly went too.”

“Let me see, isn’t he the man you don’t like at the Laboratory?”

Hope hesitated a moment.

“I don’t like him very much,” she said in what Enid privately called her “keep off the grass” tone.

“And was he?—I mean, did anything happen to him?”

“Oh, no. He was not even with them in the ‘plane. You see, it wasn’t on the journey out or back. It was on quite a short trip across country. They were going to see some old friends in North Carolina before coming home. Doctor Tamberly stayed on in New York. It was through him and his mother that I’ve had most of the news.”

“Is he back in this country?”

“Not yet. He’s expected back at the week-end, and I’m to go down with the twins to stay there with his mother and see him as soon as he arrives. It’s not a question of his having any more news for us. We—we’ve had all there is, I suppose. But there are business arrangements. He knew a lot about Daddy’s affairs and what he wanted done.”

Enid nodded sympathetically. The despised newspapers had at least imparted the information that Basil Arning had lived two or three days after the accident. No doubt this Dr. Tamberly knew all about his final wishes in connection with his children.

“Your father did like Doctor Tamberly, didn’t he?” she asked, more for something to say than for any other reason.

“Oh, yes. He’d worked with him ever since he came as a student twelve or thirteen years ago. Daddy thought him marvellously brilliant—which he is, of course,” Hope added with an air of cool but scrupulous fairness.

“And the mother?—what’s she like?”

“I hardly know her. Good-looking, with a lot of surface charm. I suppose you’d call her worldly. I don’t think anything goes very deep with her.”

“Hm. It doesn’t sound as though it’s going to be much of a week-end for you, poor poppet,” said Enid, who could use a ridiculous expression to convey real feeling.

“I thought that too,” Hope confessed with a rueful smile. “But I shall have Tony and Bridget with me They help a lot. Besides, if you have someone to feel responsible for you can’t notice or mind other things so much.”

“No. Of course not. How old are they now? Ten?”

“No, no. Twelve, and very much aware of it.”

Hope’s smile as she spoke of her young brother and sister was neither rueful nor wistful. The very thought of them evidently gave her intense pleasure, and Enid thought: ‘How pretty she is when her face lights up like that.’

So far as Enid was concerned, “pretty” covered all types of feminine good looks, but it was not really at all the word to describe Hope. Enid herself perhaps—but not Hope, with her large and remarkably well-spaced grey eyes, her smooth creamy skin and her beautifully burnished copper-colored hair. And there had always been what Enid called “that something” about her, even when they were girls at school together. Now, with the added gravity and air of responsibility which circumstances had put on her, she was something very near beautiful.

“Well, my dear, I’m afraid I must be going now.” Enid slipped her arms into the sleeves of her fur jacket and applied a very large pink powder puff to her small, upturned nose. “I promised Brian I’d meet him at six, and you know what the very best of fiancés are if you keep them waiting more than ten minutes. They may be yours till death and all that, but give them a draughty corner and a quarter of an hour’s wait and where is all the devotion, I’d like to know?”

Hope laughed as she too got up.

“It’s frozen to death, I should think, and quite right too. I wouldn’t love anyone who kept me waiting in the cold.”

“You, my pet?” Enid looked at her with sudden amused shrewdness. “You certainly would. You’re the kind that’s usually much too good to its menfolk.”

Hope flushed unexpectedly.

“I don’t know why you say that. I’ve never—”

“No, darling, because you’ve never been in love yet. But you have a passion for looking after and protecting the people you do love. So when you do fall in love, remember it’s the man’s business to do all the protecting and looking after and putting up with unpleasantness. The Almighty made them that way, and I, for one, am quite satisfied with the arrangement. Don’t try to reverse a law of nature. Funny things happen if you do.”

“You’re quite absurd,” Hope declared with a laugh, as she kissed her good-bye.

“All right,” Enid said equably. “But remember what I’ve said, when you do fall in love.”

When you do fall in love!

When Hope came back into the room after seeing Enid off, she didn’t sit down again, but walked softly up and down, her hands clasped together in front of her, and her eyes shining with an excitement which would have astonished Enid beyond measure.

Why hadn’t she said anything to her old friend about Richard? Enid was discreet enough, in spite of her apparent fluffiness and inconsequential air. Enid would have wished her so well—been delighted to know of her friend’s happiness.

Or would she?

Would she have made what she would have called “practical objections,” and tried to point out one or two aspects of the case—quite unimportant ones—which did not exactly square with what she would consider a good match?

Anyway, it didn’t matter. She had

not

told Enid—not for the moment. After all, Enid had come to talk about her parent’s death...

Hope paused in her restless walking, and stood looking down into the fire.

How was it possible to be so stunned and miserable and yet so excited and happy? Was it wrong to be able to feel such joy in the thought of Richard, when her parents

—

whom she had loved dearly—had been dead less than a fortnight? Ought one feeling to wipe out the other? Or was it possible for them to exist side by side, neither detracting in any way from the other?

“I’m not any less horrified about Mother and Daddy because I love Richard,” she said slowly and aloud, because that made it more convincing than if she just thought it. “But I can’t be less happy about Richard because of this awful thing that’s happened. The two are

different

.”

If only her mother and father could have known Richard first—got to like him—approved of him, to use the funny Victorian phrase which conveyed so much more than all the other expressions which had superseded it.

As Hope began to clear away the tea-things she unwillingly turned the phrase over in her mind.

Approved of him. No—it was no good pretending about it. Her parents would

not

have “approved of” Richard. At least, not at first and not as a prospective son-in-law. That was why she felt vaguely and miserably guilty when she knew the thought of Richard made her happy in spite of the tragedy of her parents’ death.

If she could have thought, “They would have been so happy to know that Richard would console me,’ it would have been quite a different feeling. But they wouldn’t have thought that at all. Not until they had really got to know him, at any rate.

Later on, of course, she would have been able to convince them that it didn’t much matter about his having no money and not much of a position. They would have seen for themselves that anyone so brilliant and so hard-working was bound to be a success—or as much of a success as was necessary. But there had been no later on. She had to take her stand on her own convictions and judgment.