Away From Her

Acclaim for Alice Munro

“No one working today can write more convincingly about ‘the progress of love’ than Alice Munro.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“Alice Munro is the living writer most likely to be read in a hundred years. … Her genius, like Chekhov’s, is quiet and particularly hard to describe, because it has the simplicity of the best naturalism, in that it seems not translated from life, but, rather, like life itself.”

—Mona Simpson, The New Republic

“Munro’s stories are composed with a clarity and economy that make novel-writing look downright superfluous and self-indulgent.”

—A. O. Scott, The New York Times Book Review

“[Munro’s] writing never loses its juice, never goes brittle; it also never equivocates or blinks, but simply lets observations speak for themselves.”

—Lorrie Moore, The Atlantic Monthly

“Alice Munro spins tales that show us, again and again, and with wondrous grace, how much can be done in a simple short story.”

—Pico Iyer, Time

“It has been remarked that there is almost always something open-ended, unexplained, or incomplete in Munro’s work. But this deliberate refusal to weave in all the loose threads makes her stories seem more authentic, since this is what real life is like.”

—Alison Lurie, The New York Review of Books

“Munro is the illusionist whose trick can never be exposed. And that is because there is no smoke, there are no mirrors. Munro really does know magic: how to summon the spirits and the emotions that animate our lives.”

—The Washington Post

“In Munro’s hands, a short story is more than big enough to hold the world—and to astonish us, again and again, with the choices forced upon the human heart.”

—

Chicago Tribune

“Nothing in a Munro story ever feels contrived. … [She] sings, and her women are heroic. They endure the lives produced by their choices and the fates, and they endure in the mind of the reader.”

—

The Boston Globe

“From a markedly finite number of essential components, Munro rather miraculously spins out countless permuta tions of desire and despair, attenuated hopes and cloud bursts of epiphany.”

—

The Village Voice

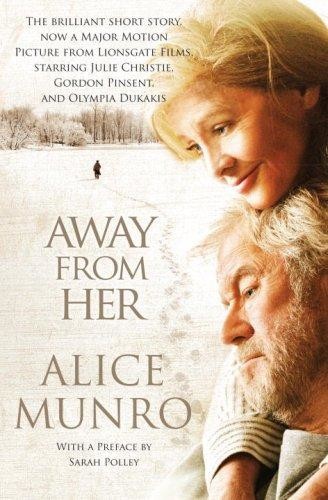

Away from Her

Alice Munro grew up in Wingham, Ontario, and attended the University of Western Ontario. She has published more than ten collections of stories as well as a novel,

Lives of Girls and Women.

During her distinguished career she has been the recipient of many awards and prizes, including three of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Awards and its Giller Prize, the Rea Award for the Short Story, the Lannan Literary Award, the W. H. Smith Literary Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her stories have appeared in

The New Yorker

,

The Atlantic Monthly

,

The Paris Review

, and other publications, and her collections have been translated into thirteen languages. Alice Munro and her husband divide their time between Clinton, Ontario, near Lake Huron, and Comox, British Columbia.

ALSO BY ALICE MUNRO

The View From Castle Rock

Runaway

Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage

The Love of a Good Woman

Selected Stories

Open Secrets

Friend of My Youth

The Progress of Love

The Moons of Jupiter

The Beggar Maid

Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You

Lives of Girls and Women

Dance of the Happy Shades

Preface

Every now and then, a piece of writing enters your life and collects seemingly unrelated threads, tangling some of them together, straightening out a few, until an articulate pattern is embroidered. One you could have never made yourself.

“The Bear Came Over the Mountain” entered my life when I was twenty-one years old. It crept right into me, had its way with me, and shifted my direction in ways I didn’t understand until years later. I am not an academic, nor a writer (I don’t consider the adaptation of other people’s stories serious writing), so I feel ill equipped to complete the task ofwriting this preface other than from a purely personal point of view. I believe I can say, without danger of overstatement, that I have had a relationship with this story that has been as powerful and as transformative as any I have had with another human being.

I first read the story on a plane on my way home from Iceland, where I had just finished acting in a film with Julie Christie. My grandmother was gradually losing her grip on her independence and on her memory. My romantic life was in tatters. (These details are only relevant to one another in the context of my own reading of the story. As the details of someone else’s life are only relevant to their reading of it. That’s one of the strangest things about the adaptation of fiction into film. You can never claim that it’s faithful to anything but the story that you read, at that moment, in those particular circumstances. The person next to me, who may also have been reading that week’s

New Yorker

on the plane from Reykjavik to London, could have easily read another story entirely.) The film that I made,

Away from Her,

may seem blasphemously untrue to what another reader may see in it, though I painstakingly honored the story that I loved.

I’ve always admired Alice Munro’s writing, but this story punctured something. I read it, stunned,and let it sit there. It seemed to enter like a bullet. So concise and unsentimental, nothing to cushion the blow of its impact. When I was finished, I couldn’t stop weeping.

I returned to it many times in the following months, trying to make sense of the hold it had over me. First, there was Julie Christie. I had met her on the set of Hal Hartley’s film

No Such Thing

. It had been a magical time, being exposed to someone so essentially curious and alive, and as Alice Munro writes about Fiona, “not quite concealing a private amusement.” It was compounded by meeting her in such a stunning and strange place. And it was a wonder to discover it with her. It was immediately impossible to not imagine Julie’s face when Fiona was described in the story. (And the coincidence of Fiona’s Icelandic background was odd, to say the least.)

Meeting Julie was a kind of salvation for me and distracted me from the exhilarating mess I had been making of my life. In retrospect, I wonder if it isn’t part of the job description of being in your early twenties to make a mess of things. If it is, then I was excelling at my work. I had one unstable, destructive relationship after another, and I didn’t want it any other way. I was a love glutton, addicted to melodrama, and convinced that happiness was the stuff boredom was made of. In the middle of thisheartwrenching, hugely stimulating time, I met a film editor named David.

He was a respected editor in Canada, and he agreed to guide me through making my first short film. I immediately liked him, his dry humor, his achingly empathetic eyes, his introspection, the compassionate way he listened when others told stories, his lack of need to take over a room. I loved sitting next to him in the dark in front of the Avid editing system as we talked about images, sound, and the emotional narrative of two other, fictional people. After the film was complete, I stalked him until he dated me, and when, after three weeks, he hadn’t fallen in love with me, I was hurt, and possibly furious. I confronted him. Looking back, I am in awe of the gall it takes to “confront” someone over not falling in love with you.

He was patient with me. He explained that he didn’t believe that love was the name for the butterflies he had in his stomach after three weeks. The butterflies were there, but he didn’t think they were … important. I believed that initial obsession was the main signal, the chief aim of coming into contact with someone you were in love with, and didn’t understand his apparent disregard for irrational passion. If he felt these things as he was claiming to, why wouldn’t he call it love?

He talked about his parents, how they had been together for forty-five years, and how sometimes, as his mother washed the dishes, her husband would approach her as she worked, slip his arms around her waist and lightly kiss the back of her neck. He thought that this

endurance

was the definition of love, not that initial insanity. If something remained, some inexplicable, intangible thread managed to stay unbroken, after the betrayals, the hurt, and the disappointment that any marriage must surely endure, then that was what he was willing to concede must be love.