Authorisms: Words Wrought by Writers (2 page)

Read Authorisms: Words Wrought by Writers Online

Authors: Paul Dickson

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day: then shall our names.

Familiar in his mouth as household words.

Acorns to Oaks

The question this raises is how do words make it into the realm of the household word at a moment when the language seems to have more than enough words to sustain itself. It is one thing to create a new word or catchphrase and quite another for one of your lexical offspring to find acceptance. As John Moore wrote in his book,

You English Words

, “The odds against a new word surviving must be longer than those against a great oak-tree growing from any given acorn.”

The author of this book has created more than fifty new words and new definitions for old words and all but two of them have thus far failed to germinate and have been relegated to the category of nonce words, a lexical purgatory for words used rarely and in the context of their creator.

My two neologisms appear as entries in the body of this book. One is

word word

for a word that is repeated to distinguish it from a

seemingly

identical word or name (a

book book

to distinguish the prior work in question from an e-book), a term that now shows up in several major reference books. But my bigger success as a neologizer has been the word

demonym

. It was created to fill a void in the language for those common terms that define a person geographically—for example,

Angeleno

for a person from Los Angeles. I have used the term in several articles and books and was pleased to note in 2013 that it had 3,870,000 Google hits. Then in April 2013 the term was used by the American nonfiction master John McPhee in the

New Yorker

. It seems that he collects books on American place-names and demonym has become part of his natural vocabulary.

6

Coined or Collected—Mind or Mined

A dilemma posed by the author of this book is the issue of words actually coined by a writer versus those the writer acquired from someone or someplace else but that they have been credited with.

In 1900, a writer named Leon Mead actually wrote to Mark Twain to ask him if he had coined any words. Twain replied that he knew of no words he had coined that had become part of the language, but that he had given currency to some that were already in use, particularly words and phrases he had extracted from the Western mines.

Mead responded, “I think it is safe to say that Mark Twain has not only popularized words and phrases which might have died but for his tonic treatment of them, but has coined others which have become familiar, at least in our vernacular.” He added that the same may be said of Bret Harte (1836–1902), the American author and poet best remembered for his accounts of pioneering life in California who was getting his new words from those around him in locales like Poker Flat and Red Gulch.

7

Twain’s point about the mines was important and he would expand on it, elsewhere insisting that many of the words and phrases attributed to him were actually things he had heard on the Mississippi River and points west. To Twain the language created in the wake of the Gold Rush was the richest. He once wrote: “The slang of Nevada is the richest and most infinitely varied and copious that has ever existed anywhere in the world, perhaps, except in the mines of California in the early days. It was hard to preach a sermon without it and be understood.”

Examples from Twain that came out of the mines and mining camp included

struck it rich

, which quickly applied to any human success;

up the flume

, signifying failure;

hard pan

, meaning a solid paying basis;

petered out

, which suggests a gradual decline and final suspension of resources;

grubstake

, the assistance given a new business enterprise on condition of a share in prospective or possible profits;

bonanza

, meaning sudden wealth or good fortune; and

squeal

, meaning to confess and betray companions. Twain is also credited by the

OED

with the first use in print of

blow up

(to lose self-control) in 1871, of

slop

(effusive sentimentality) in 1866, and of

sweat out

(to endure or wait through the course of) in 1876.

The issue of new words that are coined by the author vs. recording the words that are heard on the streets—or the mines and mining camps of the wild west or the inns and taverns of Stratford-on-Avon—applies to any writer who draws from the real life around him or her. As Leon Mead also pointed out, “The main secret of Dickens’ popularity was that he knew his types; their counterparts were in real life. They talked the argot of the London slums, the bombast of the Old Bailey, the sycophantic phrases of the counting-room, the cockney jargon of the slap-up swells.”

8

So the caveat issued with this book is that some of the coinages were second strikes.

A MAN GOT TO DO WHAT HE GOT TO DO.

Phrase that appears in American novelist

John Steinbeck

’s (1902–1968)

The Grapes of Wrath

in chapter 18 when Casy says, “I know this—a man got to do what he got to do.” This phrase is often attributed to John Wayne and to the lead character in the movie

Shane,

who utters lines similar to but not exactly this one.

1

A MODEST PROPOSAL.

Name for an outrageous proposal. The phrase is used commonly to describe heavy-handed satire. It comes from the name of such a satire with the full title

A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland, from Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick

, written by Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer, poet, and cleric

Jonathan Swift

(1667–1745), in which he suggests that the Irish eat their own children or sell them as food. Swift was Irish and deeply resented British policies toward the Irish and his insane proposal was an attack. In a letter to Alexander Pope in 1729 he wrote, “Imagine a nation the two-thirds of whose revenues are spent out of it, and who are not permitted to trade with the other third, and where the pride of the women will not suffer [allow] them to wear their own manufactures even where they excel what come from abroad: This is the true state of Ireland in a very few words.”

2

ABRICOTINE.

Apricot-colored. A nonce word created by poet

Edith Sitwell

(1887–1964) and employed in one of her poems. Nonce words are words made up for a specific, usually one-time use in literary pursuits. Counting her book of poetry, the

OED

in which

abricotine

is listed, and its appearance here, it would seem among the rarest of words. However, the 2013 online edition of the

OED

contains no less than 4,419 nonce words of which this word is the first in alphabetical order. The last is

yogified,

a nonce word

meaning to be treated in a yogic manner. It was created by

E. M. Forster

( 1879-1970).

3

ACCORDING TO HOYLE.

According to the highest authority; done with strict adherence to the rules.

Coined in this sense in 1906

by

O. Henry

(1862–1910), which was the pen name for William Sydney Porter, an allusion to the books of card and game rules written by Edmond Hoyle.

4

AFGHANISTANISM.

A term coined by

Jenkin Lloyd Jones

(1843–1919), a former member of the National Conference of Editorial Writers as well as columnist and editor of the

Tulsa Tribune,

to

describe the journalistic practice of concentrating on problems in distant parts of the world while ignoring controversial local issues. He explained, “It takes guts to dig up the dirt on the sheriff, or to expose a utility racket, or to tangle with the governor. They all bite back and you had better know your stuff. But you can pontificate about the situation in Afghanistan in perfect safety. You have no fanatic Afghans among your readers. Nobody knows more about the subject than you do, and nobody gives a damn.”

5

AGEISM.

Prejudice or discrimination based on one’s age. A term coined by physician and author

Dr.

Robert N. Butler

(1927–2010), who believed that as a society we should think about individual function, not age. Butler is known for his 1975 book

Why Survive? Being Old in America

, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1976. He believed that society should confront ageism and work on constructive solutions to ameliorate it.

6

AGNOSTIC.

A term coined by English biologist and author (and grandfather of Aldous and Julian Huxley)

Thomas Henry Huxley

(1825–1895) in 1869 to indicate “the mental attitude of those who withhold their assent to whatever is incapable of proof, such as an unseen world, a First Cause, etc. Agnostics neither dogmatically accept nor reject such matters, but simply say agnostic—I do not know—they are not capable of proof.” Huxley was apparently tired of being called an atheist when he created this distinction.

7

AHA MOMENT.

A sudden realization, inspiration, insight, recognition, or comprehension. When this word was added to the 2012 edition of

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary,

much was made of the fact that television personality

Oprah Winfrey

had popularized the phrase in interviews with guests when moments of sudden insight occurred. The term actually made its debut in 1939 in the textbook

General Psychology,

written by

Lawrence Edwin Cole

, (1899-1974) in which he uses it to describe the moment of insight. The

OED

notes that Chaucer used “a ha” in this context in about 1386 in

The Nun’s Priest’s Tale

: “They cried, out! A ha the fox! and after him thay ran.”

8

ALL HELL BROKE LOOSE.

This phrase originated in

Paradise Lost

by

John Milton

(1608–1674). At the end of book 4, the angel Gabriel asks Satan why he came alone and “Came not all Hell broke loose?” Milton created several other well-known demonic phrases:

better to reign in hell, than serve in heav’n

is his as is

pandemonium

.

9

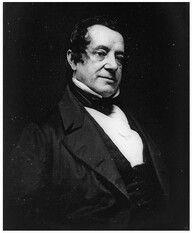

ALMIGHTY DOLLAR.

American money as a tool of power, a term coined by American author and diplomat

Washington Irving

(1783–1859). It appears first in a story of his called “The Creole Village” in 1836. “‘The almighty dollar,’ that great object of universal devotion throughout our land, seems to have no genuine devotees in these peculiar villages.” Irving was the first American author to make a living from writing novels.

10