Atlantis Beneath the Ice (30 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

Beginning with Cuvier back in the eighteenth century, a succession of daring intellectual explorers have been braving the disapproval—sometimes the opprobrium and derision—of their academic colleagues, trying to account scientifically for these anomalies and to write the true scenario of the shattering events responsible for all those myths and legends.

The situation is like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle with most of the pieces originally missing. Early attempts to assemble the puzzle ended up with more holes than pictures and were relatively easy to ignore or dismiss. But as modern science develops, new pieces to the puzzle keep turning up. Successive attempts to put the whole picture together grow increasingly cogent.

The Flem-Aths are perhaps the most persuasive and daring of the contemporary “Atlantologists.” Underpinned by the absolutely irrefutable fact of mass mammal extinctions around 10,000 BCE and the precise, detailed, and no less irrefutable testimony of the Piri Reis’s and other maps of the pre-catastrophe world, the picture becomes increasingly coherent. A spectrum of relevant disciplines—geology, paleoclimatolgy, cartography, astronomy, comparative religion—all contribute to the puzzle, and Hapgood’s earth crust displacement theory seems to provide the

modus operandi

that accounts for the whole, huge, worldwide scenario in a single stroke.

Will the Flem-Aths’ contemporary portrait finally take root and prevail? It is a big question. All of our human distant past hangs in the balance, along with the true story of the evolution of human civilization on earth.

APPENDIX

A GLOBAL

CLIMATIC MODEL

for the Origins of Agriculture and the Sequence of Pristine Civilizations

This is the original text submitted in the spring of 1981 to

The Anthropological Journal of Canada

and accepted for publication. It contains

more

information than the edited and published text (see Flem-Ath, “Global Modal”) and appears here in full for the

first

time.

ABSTRACT

A climatic model orders archaeological evidence on the

origins of agriculture and the sequence of independent

civilizations on a global scale.

Why did agriculture become the preferred means of subsistence following the termination of the Pleistocene? Why did the civilizations of the New World take so much longer to evolve despite the fact that their early agricultural experiments are contemporary with those of the Old World? This paper will attempt to shed light on these problems with the aid of the little-known climatic model of Hapgood

1

in conjunction with the stress model of Harris.

2

Cohen

3

has argued, quite rightly, that it is no longer adequate to explain the “where” and the “when” of agricultural origins but to address ourselves to the more important question of “why?” Why did mankind, in both the Old and New Worlds, almost simultaneously shift from their highly successful and traditional subsistence of hunting and gathering to agriculture? Why were certain areas of the world more suitable to this adaptation than others? Any theory, which attempts a global approach to this problem, must confront the question of “why” in such a manner as to illuminate the data concerning the “where” and “when” of the origins of agriculture.

Global theories, which have addressed this problem, have fallen into three categories: the diffusion models; the population/ecological models; and what I term the “traditional” climatic models. Why have these models failed to account for major significant archaeological evidence?

The fact that “. . . all agricultural origins fall about 10,000 ± 2000 years ago,”

4

well before the first civilizations, coupled with the evidence demonstrating more than one center of early agricultural experimentation

5

has seriously undermined the concept of diffusion as an important model for the origins of agriculture. Until a theory is developed which can overcome these two problems the theory of diffusion will remain untenable as a global model.

a

Cohen attempted to apply a population/ecological model on a global scale. Following Boserup

6

who first put forward the idea of population density as a causal feature of technological change, thus reversing the traditional Malthusian model, Cohen argued that population growth worldwide reached a saturation level, which in turn created a stress condition, forcing the adoption of agriculture as a new strategy of food supply. This thesis suffers from three very serious drawbacks: first, it flies in the face of anthropological data, which, as shown, indicate

that hunter-gatherers

normally

maintain equilibrium with their environments;

7

second, given that the population of density of the Old World was significantly greater than the New World, Cohen’s theory fails to explain why the ecological thresholds were reached

at the same time;

and finally it does not address itself to the evidence of Vavilov,

8

which shows a direct correlation between high altitudes and the centers of agriculture. In short, although Cohen has addressed the problem of “why,” his model does not shed light on the “when” and “where” aspects of the problem.

The diffusion and population/ecological global models have difficulties in explaining archaeological data and so we now turn to the “traditional” climatic models. These theories, such as Childe

9

and Binford

10

have suffered as Cohen correctly pointed out,

11

from two problems: they are regional in scope and thus cannot account for the data on a broader perspective; and they are repetitive processes, which fail to explain why the particular changes of the post-Pleistocene period resulted in agriculture, when similar events in the past had not done so. Any new climatic theory must address these two problems.

Before we proceed to the primary thesis of this paper it may be helpful to describe the type of theory that is required. We need a theory that can explain “why” the process of agriculture began in the New and Old Worlds at approximately the same time yet led to much different rates of cultural evolution. The model must not only address this “when” evidence and especially the long-neglected correlation between altitude and centers, but the theory, if it is a climatic one, must address itself to the traditional limitations of repetitive and regional effects outlined by Cohen. Finally the theory should address the data on a global scale.

A climatic model based on the geological theory of Hapgood in conjunction with the stress model of Harris can meet all the requirements stated above. The sad state of affairs is that Hapgood’s geological work has simply been ignored despite the fact that the original volume was prefaced by the late Albert Einstein. Einstein’s preface is an excellent

summary of the basic theory and since the book is now out-of-print, I have taken the liberty of quoting him:

I frequently receive communications from people who wish to consult me concerning their unpublished ideas. It goes without saying that these ideas are very seldom possessed of scientific validity. The very first communication, however, that I received from Mr. Hapgood electrified me. His idea is original, of great simplicity, and—if it continues to prove itself—of great importance to everything that is related to the earth’s surface.

A great many empirical data indicate that at each point of the earth’s surface that has been carefully studied, many climatic changes have taken place, apparently quite suddenly. This, according to Hapgood, is explicable if the virtually rigid outer crust of the earth undergoes, from time to time, extensive displacement over the viscous, plastic, possibly fluid inner layers. Such displacements may take place as the consequences of comparatively slight forces exerted on the crust, derived from the earth’s momentum of rotation, which in turn will tend to alter the axis of rotation of the earth’s crust.

12

It should be noted that the process of earth crust displacement (ECD) refers only to a movement of the earth’s crust and

not

to the mantle, core, or pole of rotation. Put simply, ECD is a process, which results in various parts of the earth’s crust being shifted, at different times, over the earth’s axis (the North and South Poles).

Working on the assumption that the earth’s magnetic fields are usually located in close proximity to the pole of rotation, Hapgood collected geo-magnetic rock samples from different parts of the globe indicating those areas of the crust, which were at the poles from the last three ECDs. Hapgood found evidence that the most recent ECD occurred between 17,000–12,000 BCE, at which time the crust displaced resulting in the North Pole’s relocation to its current place in the “Arctic” Ocean after having been located previously in the Hudson Bay region

of northern Canada. More recent climatic data from different sources have been brought together

13

indicating at dramatic climatic change at 12,000 BCE, which coincides with Pleistocene extinctions, rising ocean levels, the close of the ice age, and the origins of agriculture.

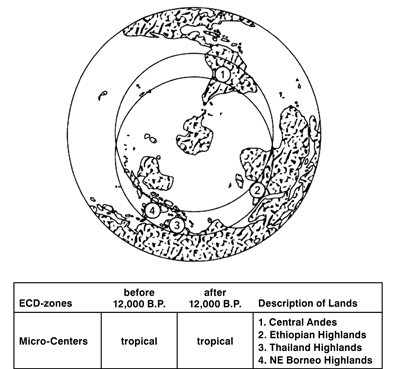

A displacement of the earth’s crust causes dramatic climatic changes, but it should be noted that these variations are not all equal in their impact. There were areas of the globe following the ECD of 12,000 BCE that were tropical before

and

after the event. Taken in conjunction with the data of Vavilov

14

I have labeled these areas as “Micro-Centers” because the further one travels from the midpoint between the current and previous equators, the less likely that one will be able to survive the harsh ecological changes (see

figure A.1

).

Figure A.1.

Tropical agricultural origins.

Vavilov found a direct correlation between agricultural origins and land over 1,500 meters above ocean level. This long-neglected data is explicable in terms of ECD because the displacement of the crust results in immense tidal waves. Survivors of the event have a strong motive for staying in high mountains. The Micro-Centers listed in

figure A.1

are over 1,500 meters above ocean level.

Important archaeological discoveries in three of the four Micro-Centers date agricultural developments to approximately 12,000 BCE. MacNeish

15

reviews the archaeological evidence in Peru dating to this time range, while Pickersgill and Heiser

16

delineated the number of important crops, which were domesticated in the Lake Titicaca region of Bolivia/Peru. The same sort of data comes from the antipode of Lake Titicaca in the highlands of Thailand. Early agricultural experiments at Spirit Cave, Thailand, are reviewed by Solheim

17

and Gorman.

18

Similar evidence near the Ethiopian highlands is found in Wendorf.

19

The model suggested here indicates that more excavations might be profitably undertaken in the highlands of northeastern Borneo.

ECD creates a situation where mobility is limited and important plants and animals for man become extinct.

20

This is exactly the condition that Harris argues leads to the process of agriculture. According to his model, an immobile population creates population pressures, which intensify wild-food procurement with eventual improved seasonal scheduling. A resource specialization coupled with improved technological innovations and a cultural selection of specific plants or animals may develop into a genuine food-producing system. If mobility is restored this last phase may not take place and a reversion to huntinggathering can take place.