Atlantic (33 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

But their long sojourns in the Atlantic gave American sailors a confidence and a profound knowledge of the deep sea that was shared by few others. Whalers ranged to the farther ends of the ocean and discovered as many of its secrets as did the navigators and surveyors sent out by the maritime states: their legacy—and especially the legacy of New England whalers in the Atlantic—is profound.

4. THE PASSAGE OF GOODS

So it is scarcely surprising that when regular cargo crossings of the ocean emerged as a new means of performing transatlantic business, the Americans, long-distance specialists in this particular sea, rose to the occasion and pioneered a form of shipping that has dominated the Atlantic ever since. The development occurred in the first cold days of January 1818—and it involved the sailing, eastbound from New York, of what came to be known as a

packet ship

.

The Atlantic was thick with cargo ships already—carrying toward Europe immense tonnages of New World cargoes, most especially sugar from the various plantations of the Americas, Brazil, and the Caribbean islands, and carrying back toward the Americas the trade goods and construction supplies and items of up-to-date technology and fashion that the merchants of the colonies demanded. But these ships generally sailed only when their holds were filled up with cargoes—there was nothing regular or reliable about departures or arrivals, nor any certainty about the routes a vessel might ply: a last-minute arrival of freight bound for a hitherto unspecified port, once accepted by the supercargo, meant the ship had to divert to ensure making the delivery.

The one oceanic shipping service that did attempt to have a schedule, and even tried to keep to it, had been organized by the fledgling British Post Office almost ever since Charles II first established a mail service in 1660. It was recognized very early on that important foreign mails—official letters to embassies and colonial governors, as well as dispatches to the leading citizens of faraway places—needed to be accommodated as well as those bound for domestic destinations. Accordingly a number of postal packet ports were created in the early 1680s—at Harwich and Dover for ships carrying mails to northern Europe, at Holyhead on the Isle of Anglesey for the Irish mails, and, after its formal selection in 1688, at the remote seaside town of Falmouth in southern Cornwall.

Fast and regular sailing ships were dispatched from Falmouth to all corners of the Western world—at first with a service every two weeks to Corunna in Spain (using small vessels known as advice boats, the first of which were called the

Postboy

and the

Messenger

), and which then went through the Strait of Gibraltar for onward transmission to the rest of south and central Europe and Asia.

63

Then at the turn of the century, the navy’s surveyor general, Edmund Dummer, proposed to the Post Office its first transatlantic service, and by 1702 he was running, as an early kind of franchise, a quartet of oceangoing sloops and brigs between Falmouth and the British-run sugar islands of Barbados, Antigua, Montserrat, Nevis, and Jamaica. From the Caribbean it was but a short step to running a service to the American mainland, and in particular New York City—this service was inaugurated in 1755, with initially two vessels, the HMP

Earl of Halifax

and the HMP

General Wall

. Once this route was in full swing, with supposedly one boat a month (though there were only four voyages in the first two years), still more vessels were commissioned into service, eventually with British routes running from Falmouth to such southern ports as Pensacola, St. Augustine, Savannah, Charleston, and, most important of all in the early years, the major northeastern American garrison city (and spermaceti-candle-making city) of Halifax.

A sporadic service, run mainly for the carriage of military mails, had already been operating between Falmouth and Halifax since 1754. Not surprisingly it had run into logistical difficulties during the War of Independence. But once that dust had settled and America had her freedom, a formal and regular service was put into operation, in 1788—with both Halifax and New York receiving mails from Falmouth—and in the case of the latter, all organized under the supervision of the presiding genius of Benjamin Franklin, colonial America’s deputy postmaster general, and after independence, the new nation’s postmaster general in chief.

64

All of sophisticated London became swiftly familiar with the routines: on the first Wednesday of every month, mails would be made up at the General Post Office in central London for New York, Halifax, and Quebec City. A letter for Manhattan cost

four pennyweight of silver

. The leather

packets

of collected mails—from which packet boats got their name—were then put on the mail coach on the post road to Falmouth, and arrived on Saturday evening, as regular as clockwork, and were transferred to the waiting boat, which promptly made her way out of the Falmouth roads and into the swells of the Atlantic. It took on average fifty days to beat across the ocean,

uphill

,

65

especially if the Post Office added stops at Bermuda and Nova Scotia en route. A Londoner who posted a letter on the first of January could expect it to be read in New York City during the third week of February.

And it was not only the mails, of course: the comptroller of the Post Office, a Mr. Potts, let it be known that newspapers and magazines could be sent across the Atlantic as well. Any one of the London daily papers, such as the

General Advertiser

, the

Courant

, or the

Daily Advertiser

, set the reader back five pence a copy. The

Spectator

—still in print today—cost nine pence, and the official

London Gazette

—the most venerable of London papers, and still going strong, offering up the government’s official pronouncements—was available in New York at nine pence a sheet, “to be delivered by the commanders of the several packet boats, free of all other charges.”

It seems more than a little strange that it took as long as 130 years, from 1688 until 1818, for the notion of sending regularly scheduled packets of mail to be extended to the shipping of general cargoes. And in a sign, perhaps, of things to come, it was not a British institution that first came up with the notion of doing so, despite all the experience the British had accumulated. The invention of regular transatlantic cargo shipping came from a company headquartered in America.

In fact, both of the brains behind what turned out to be a truly game-changing venture were Britons, living in America. Both were Yorkshiremen, both from Leeds, and they had each come to seek their fortunes in America at the very end of the eighteenth century. By coincidence they occupied offices next door to each other on Beekman Street in lower Manhattan. By 1812, when the idea of the venture was first born, Jeremiah Thompson was a young cotton broker and owner of a small number of ships in the American coastal trade, and Benjamin Marshall—who, like Thompson, was a Quaker, as were most of the merchants in this small saga—a textile manufacturer and importer.

Both men soon found they had developed parallel interests in buying raw cotton direct from the plantation markets in the southern American states. To be sure, they had different plans for the cotton: Thompson wanted to buy his so he could market it in exchange for the fine woolen goods his father was making back in Leeds and was trying to export to America. Marshall, on the other hand, found that he needed large quantities of cotton to send back to his family’s mills in Lancashire, where they would be made into textiles that he would then ship back to New York and sell on to retailers. The two men, not entirely competitors, then decided to work in concert, and they set up offices in Atlanta, with agents in New Orleans: absent any other internal freight system,

66

they used their small vessels to ship cotton from the southeastern ports up to New York and then, by whatever vessels happened to be available, across the Atlantic to Liverpool.

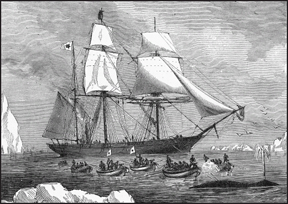

A flotilla of dories

, each carrying the pennant of their mother ship in the event of being lost in heavy seas, bears away to harpoon a pod of right whales basking in an unusual high-latitude calm.

And herein lay both a problem and, from Marshall and Thompson’s point of view, a tremendous business opportunity.

The problem was one that became hugely amplified by the sudden jump in trade that followed the ending of the War of 1812 and the lifting of the Royal Navy’s fitful blockade of American ports. For there were simply not enough ships leaving New York that offered cargo space across the ocean—and, moreover, no one knew when those ships would leave New York, or when they might arrive at the other side of the Atlantic.

For years it had been the custom for merchants to own their own ships: Marshall and Thompson already owned three vessels, the

Pacific

, the

Amity

, and the

Courier

, which they used for their own Atlantic cotton-shipping trade, and so they were personally well set: they did not have the problem afflicting many of their colleagues who could not find holds in which to ship goods. The particular stroke of genius of these two already highly successful businessmen, together with another Quaker shipowner, Isaac Wright—and which would ensure they were long remembered for their canny exploitation of a historically important business opportunity—was their decision to order still more ships, and to offer the space in these ships’ holds to any shipper who needed it. Further, and crucially, they sent those ships out across the ocean on a fixed and regular timetable, something that had never been done before: instead of the so-called tramp ships that had operated hitherto, and which left port when the skipper wished to, this brand-new idea of “square riggers on schedule” was offered instead.

Under this plan, a vessel of what would be called the Black Ball Line would leave New York at 10

A.M.

on the fifth of every month, bound for Liverpool. A westbound ship would leave Liverpool for the uphill leg, on the first of every month. All ships carried freight of any kind, either in the hold or lashed to the decks, for any person who would pay. They also carried passengers—as many as twenty-eight in the early ships—in some fair degree of comfort.

They departed precisely on time, as advertised, whether their holds or their cabins were empty or full: they slipped their moorings in fair weather or foul, with

getting there

, and

getting there fast

, their singular priority. And in deference to the Post Office back in England, they would give to their vessels and their service the same name: they would be packet ships.

The first-ever Liverpool packet left Pier 23, in lower New York, on morning of January 5, 1818. If proof were needed that this new service was not to be dependent on the whim of weather, tide, or the master’s mood, and that it would indeed function in fair winds or foul, the 424-ton, three-masted

James Monroe

cast off her moorings in a howling nor’easter of a snowstorm, and the mobs of fascinated onlookers who cheered her into the gale—church bells rang out, and cannon were fired, too—soon lost sight of her in the froth of spindrift and blowing snow.

As she rounded the seamark of Sandy Hook, with New Jersey to her starboard side, Long Island to port, and with the land dropping away fast as she was carried out to sea, she unfurled her headsail—and in doing so displayed to all the other ships scurrying for shelter her new signature logo, a large black circle woven prominently into the canvas. She had the same symbol on the pennant flying from her mainmast: a brilliant red streamer with a black ball, dead center.

The

James Monroe

was built for speed—this, and her fixed schedule, were the principal bait for customers—and she owed much to refinements in naval architecture that American privateers had incorporated into their cargo ships during the war, to better outrun the British blockade. She was also quite capacious: she had room for 3,500 barrels of cargo—this was the principal measure for a ship’s hold in the early nineteenth century—though on this first voyage she was nowhere near full. There was, as has been noted, room for twenty-eight passengers, but only eight had signed on—at two hundred dollars for a one-way journey. Her manifest shows her holds echoing with space, since she was taking to England short commons indeed: merely a small cargo of apples from Virginia, some tubs of flour from the Midwest, fourteen bales of wool from Vermont, a smattering of cranberries from Maine, and some canisters of turpentine produced on the slave plantations in Florida. There were also ducks, hens, and a cow, allowing the obsequious stewards—mostly black men—to offer meat, fresh eggs, and milk to the understandably nervous clutch of civilian passengers. There were bales of Georgia cotton, too: the shipowners took good advantage of their own vessel to carry back to the textile mills of Yorkshire and Lancashire yet more supplies of the magical fiber from which they had first made their fortunes.