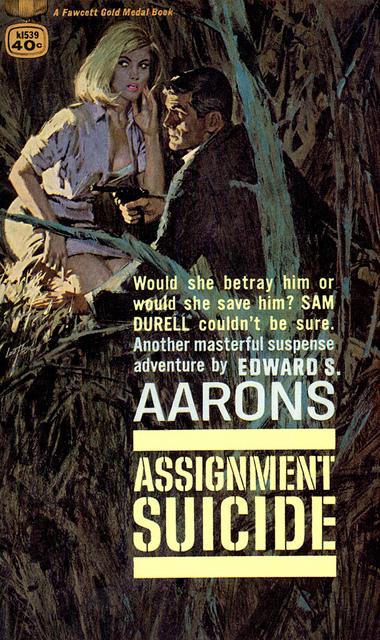

Assignment - Suicide

Read Assignment - Suicide Online

Authors: Edward S. Aarons

Chapter One

IT WAS COLD in the plane, and Durell could see nothing.

Land, sea and sky were all the same, bleak and empty, and the night was darker

than the dark anxiety inside him. The DC-3 quartered crabwise into the stiff wind,

laboring like the sturdy old workhorse that she was. There were no stars and no

moon, and as he sat beside the pilot in the dim glow of reflected light

from the instrument panel, Durell had the feeling he was isolated from all the

rest of the world. The pilot’s compartment was like an island suspended in dark

space, a fragmentary bubble illusively balanced in the cold emptiness and

liable to burst at any moment and plunge into the void all around him.

He sat quietly in the bucket seat beside the pilot and Watched

the chronometer. The pilot was young and capable, and Durell, knowing his

business, was content to let this part of it remain in the pilot's hands

without interference. Not that you could stop any of it now, any more than you

could stop time by smashing the clock in front of you. The machinery would go

on with its maze of men and plans and ambitions, whether you were here or not,

even if time stopped for you personally. Somebody else would take your place,

that was all.

“They haven't started shooting yet," Durell said.

The pilot was a Texas youngster with straw hair and a ready

grin to hide his nervousness. “We’re a good ten minutes ahead of the regularly

scheduled SAS plane. Operations gave me a plot of their course.” The pilot

grinned quickly, but his blue eyes were pale stones in the bubble of light

around them. He wore battered cowboy boots with his flying gear. The

plane bucked, bounced and settled. “Same flight pattern as the Swedes.

The radar will figure the Stockholm people are a smitch ahead of time, is

all. We hope.

I

hope. My kids and

Susie hopes. But you can’t ever tell. Give ’em credit; they’ve got the coast

tied up so a mosquito couldn’t get through without their knowing it. Are you

about ready,

tovarich

?

”

“Yes. I’m ready,” Durell said.

"You count sixty, then bounce out."

“Say hello to Susie for me. Kiss the kids.” He liked the

Texan. He hoped the pilot made it on his expected transfer back home, two weeks

from now. “When do I start counting?”

“I’ll tell you.”

The pilot had a picture of his wife taped up over the

instrument panel, and the pilot’s eyes turned as soft as a summer lake as he

looked up at the pleasant, happily smiling face of the girl he had married.

‘Start now," the pilot said. “Happy landing. And I

don’t envy you.”

“Keep a candle in the window,” Durell said.

The numbers began to tick off in his mind as he left the

bucket seat and worked back through the stripped fuselage lot the DC-3. The

parachute pack bumped and kicked at the backs of his thighs. The muscles of his

legs felt tight and knotted.

had come a

long way in a hurry: from Washington, Paris, and the airfield in West

Germany. R.S.F.S.R., here we come. The trip can end faster than it began.

Through the port, he saw a glow of light on the far horizon ahead. His German

Watch read 8:32. The Baltic Sea, the Gulf of Finland were behind them.

Leningrad was just over the edge of the arctic world. Even in April, the

weather would be bitter. But it was only the first stop—it there were any

others to follow his landing. He didn’t push that thought too far. You go one

step at a time, like an animal prowling a jungle, and that was how you hoped to

stay alive—with care and patience and luck. You always needed luck.

His counting ended.

Durell pushed his right shoulder against the escape hatch,

felt the thrust of an icy slip stream, and tumbled into space. Rain struck his

cheek in a shower of piercing, silvery splinters. Sky and land and black night

engulfed him, and he fell like a

mote

in the frozen

emptiness. Patches of snow, dark hummocks, B glint of light swung and slid and

revolved under him. He counted again, pulled the cord, felt the snap of the

pilot chute, felt the chest and groin-jarring jolt as the black nylon canopy

opened overhead.

Briefly, there was peaceful, swaying silence except

for the wind in the parachute rigging. Two thousand feet of empty night dangled

under his feet. He twisted, looked for the plane, saw the exhaust spitting

orange from the twin engines, heard the throaty bellowing of it as it banked

now in a long sweep for the safety of international waters and home. Radar

blips on green screens below would be registering the unexpected maneuver of

what had been thought to be the regularly scheduled commercial SAS plane.

Perhaps he, too, was a blip on the screens down there, hidden in the dark void,

a dot of green light on scopes where inimical eyes watched his descent.

He checked everything again as he watched the plane and

remembered the picture of the pilot’s Susie. The DC-3 banked and fled for

the safety of the sea. Check and check again. His cheap gray topcoat, his suit

of stiffly cut blue serge, tailored Russian-style, just shabby enough; his

slightly frayed white shirt; his rather flashy silk tie; the black,

square-toed shoes. McFee had made him shave off his mustache, back at 20

Annapolis Street, in Washington. Washington, where the cherry blossoms bloomed.

McFee had handed him papers and credentials, the cards stamped and sealed and

oily-fingered for age, all of which made him into Igor Vanlivov,

lieutenant, MVD, military section. What better camouflage when entering

the bears den than to appear as one of the bear’s cubs? So McFee reasoned, and

McFee was usually right. Language was no barrier. Durell spoke Russian with a

Muscovite accent. He had been here before, but not more recently than three

years ago, when he was pulled out of the field and given the desk job at

the anonymous headquarters of CIA at 20 Annapolis Street. And for three years

you chafed at the mountains of correlations, deductions, charts, graphs, reports,

analyses and syntheses of other men’s work. You ask again and again for field

assignments, and then a man is suddenly hit by a car in front of your apartment

house and he’s found dying on your doorstep, asking for you. And you get it.

And away you go, as the comedian says.

A long way from home—home being the hot, dark bayous below

New Orleans, and old Grandpa Jonathan, and a Cajun boyhood. Home was Deirdre,

with her tears as bright as the April Iain, telling you she loved you and

couldn’t help loving you always; but damn it, how could she marry a. man and

not have a honeymoon at all? Home was the last kiss, and the agreement to disagree.

Deirdre did not know where he was now, and Durell hoped she no longer cared.

It had been a warm day in Washington. Durell had been in the

hospital room since two o‘clock in the morning, and it was now nine. The man

was dead. Outside, a robin hopped back and forth on the budding branches of a

dogwood tree that grew on the lawn of the hospital, near the window. The hiss

and murmur of traffic on the avenue nearby was muted. Durell had been listening

to the rasp and rattle of Arkady Sukinin’s breathing, and now that it stopped,

he became aware of other sounds around him.

Fred Shannon came in and looked at the dead man on the bed

and looked at Durell and shrugged. “Gone, Sam?”

“A minute ago.”

“Nothing else out of him?”

“No,” Durell said. “Did you send the recordings over?"

“Sure,” Shannon said. “It‘s a kick in the ribs.”

“Where is General McFee?" Durell asked.

“Yelling for you, Sam. You look beat, pal. McFee’s been over

to the Pentagon to the Joint Chiefs and he’s been to the White House and he had

to talk to Senator Hugo, too. Red, white and blue tape. The boss leaves it all

up to the little guy. And the little guy leaves it to you.”

“Something’s got to be done,” Durell said.

“Crazy accident drops a hot bomb in your lap, hey?”

“This Sukinin didn‘t think it was an accident,” Durell said.

His eyes felt gritty from lack of sleep, and he was aware of a weariness that

went into his bones. His frustration didn't help. “Keep Jones and Isaacs on it,

Fred. And let McLarnin sit on his duff here in the corridor. Not that anybody

would be interested in what we've got left here now.”

“Roger,” Shannon said. “Maybe McFee will keep you on it.”

“Fat chance,” Durell said.

He left the hospital room, nodded to McLarnin lounging near

the floor nurse’s cubicle, and rode the elevator down to the ground floor.

He kept hearing the dead man’s strangled, pink-frothed words whispering in the

back of his mind as he reached the street. He wanted to shower and shave and

have breakfast with Deirdre, and then he remembered that Deirdre was gone and

he wouldn‘t see her again, and that was for the best, even though he already

missed her with an ache that would take a long time going away. The hell with

it. You ought to go home to Grandpa Jonathan, he told himself. Do some fishing

and play poker in the Blue Belle in the French Quarter for a few weeks.

He went to 20 Annapolis Street. . . .

Durell was a tall man, well over six feet, with heavy

shoulders and a lean waist and the delicate, long-fingered hands of a

born gambler. His hair was thick and dark, and his eyes were a deep blue that

sometimes looked black when he was angry or contemplating something dangerous.

He had a small, neatly trimmed, thin mustache. His Cajun blood made him

hot-tempered and gave him a tendency toward independent action that McFee often

deplored. There was an air of competence and alertness and self-sufficiency in

the way he moved and walked. He knew all about the strength of organized

effort, but he also knew that in his business, a spy died fast if he waited for

and depended on others. It made the difference between the quick and the dead.

No. 20 Annapolis Street was a gray stone building with a

facade indicating a routine business enterprise, and behind the cover

activities in the steno pool offices on the ground floor the real business was

conducted, behind steel doors and soundproofed corridors. Durell nodded to

Alex, on the elevator that took him up to Dickinson McFee’s little room.

General McFee was in charge of this branch of the CIA. He

was a small man with thick gray hair and impersonal eyes and a brain like an

electronic computer. His office was unadorned, and he told Durell to sit down

without ceremony and pushed a manila envelope across his big desk. “That’s

yours. Passport, papers, plane tickets to Paris. Youngman will carry you on

from there. You’ll get your clothes in Germany.”

“Am I going somewhere?" Durell asked.

“Luke Marshall asked for you, didn’t he?”

“If Sukinin was telling the truth.”

“We can’t afford to ignore it, truth or lie. You wanted to

get out of your office, didn‘t you?"

“Sure,” Durell said. “Did you get the tapes I sent over from

the hospital?"

“I heard it all. So did the boss, and Senator Hugo and an

assortment of generals and admirals. The consensus is that it‘s all hogwash.

Nobody has an ICBM ready yet.”

“Sukinin said they have it.”

McFee’s mouth was like a small trap, and he laughed without

mirth. “The Pentagon brass is running around like decapitated chickens. Their

pride is injured. They've squabbled between themselves so long, with each

branch jealously fighting for appropriations to carry on their private

researches, that they can’t face the fact that a centralized organization

working on the one project without competition might have beaten us to it.”

“Are the Russians ahead of us, then?”

“Nobody is admitting that.”

“What do you think, General?”

“I don’t know. Too much bluster and bellow here to tell. All

I got was a lecture on the complexity of defense against an ICBM. All about

dealing with a weapon going at a speed and altitude probably above mach

twenty—that‘s twelve thousand to fifteen thousand miles per hour—and

above five hundred miles in height. And the time for defense is measured

in seconds.” McFee shook his head. “Maybe we’ve got it, too. Maybe not. But

it’s for sure we’re not pushing any buttons. And Sukinin says

they

will, while they’ve got the chance

and think they're ahead."

Durell lit a cigarette and waited. McFee snapped on a switch

that started the air conditioner. He hated smoking, but he did not verbally

object to Durell’s.

“Brief me on Sukinin,“ McFee said. “I know I heard it on the

tapes. Let‘s have it filtered through that Cajun mind of yours, Sam."

Durell blew smoke toward the humming ventilator. The dead

man’s whispering went around and around in the back of his mind. “It boils down

to a simple thing. Luke Marshall, our man over there, made contact with an underground—that’s

what Sukinin said. Hell, we’ve never had an inkling of organized opposition in

Moscow’s home territory before. But Sukinin says it’s so. And Luke has their

missile bases down on a plot map. And Luke is either sick or wounded or dying.

Immobile anyway, trapped in Leningrad. Watched, fettered, and can’t move.”

Durell stood up, walked to the door, walked back again. He

felt lumpy. “Sukinin is an MVD man, but he’s also one of the underground. He

says the organization has been opposed to someone in the Politburo who wants to

punch a button, Just one, on May Day—and an intercontinental ballistic missile

takes off with an H-bomb Warhead and lands somewhere on this side of the world.

Not enough to knock us out; they know that. But enough to start us retaliating.

Then they send the rest of the ICBMS over. It’s one man’s idea, Sukinin said. A

neo-Stalinist gimmick to do away with their ‘collective leadership’ and put one

man in the saddle again. A man Sukinin identified only as ‘Z’. Nothing

more and nothing less."

“We’ve gone through their known hierarchy. We didn't find

anybody with that initial,” McFee said.

“I know that, too."

“Joint Chiefs doesn't believe they have the missile yet.“