Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (25 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

Then came Henry VIII’s younger sister, Mary. She had married King Louis XII of France, who had died before they had any children. Mary later married Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. Brandon had been brought up as a favourite at the court of King Henry VII, as his father was Henry’s standard-bearer who had been killed by King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth.

Mary had died in 1533, and her sons had died childless. So next came Mary’s older daughter, Frances. She had married Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset (the great-grandson of Elizabeth Woodville and her first husband, Sir John Grey). They had three daughters: Jane, Catherine and Mary. Therefore, accepting the illegitimacy or unsuitability of Princess Mary, Princess Elizabeth, Mary Queen of Scots, and Margaret Douglas and her son, it was Frances Brandon who was entitled to the crown. She waived her rights in favour of her oldest daughter, Jane, whom she had sent away at the age of nine to be brought up by Catherine Parr. Most importantly for Northumberland, Jane was Protestant and single; it meant that she was available to marry Northumberland’s son, who would become king. Jane married Lord Guilford Dudley on 21st May 1553.

18 Unwilling on principle to accept the divorce granted by the Pope, but wishing to free Margaret from the faithless Angus, Henry relied on Margaret’s earlier desperate claim that James IV (whose body was not found after Flodden) may have been alive when she married Angus.

In truth, Jane was seventh in line, and almost everyone knew that Princess Mary was the rightful heir; her illegitimacy was not genuine.

Conscious of the widespread support for Mary, Northumberland suppressed the news of the King’s death while he tried to capture her. However, Mary was warned of his plans, and she escaped to Framlingham Castle in Norfolk, the stronghold of the Catholic Howard family. With Mary out of the way, Northumberland had his 16-year-old daughter-inlaw proclaimed queen.

Now everything went wrong for Northumberland. First he told Jane to declare his son, Guilford Dudley, the king; but Jane refused, regarding Guilford as an arrogant bully. Next, Mary advanced on London with her forces, and Northumberland raced to confront her. Northumberland was hugely outnumbered, and in his absence the Council, accepting the inevitable, declared Mary the queen.

Northumberland surrendered. He was imprisoned, tried, convicted of treason and executed. After a reign of just nine days, Jane and her husband were sent to the Tower, never to meet again. They were convicted of treason, but Queen Mary would not consent to their execution.

Some months later, plans were being made for Mary to marry Philip, the only son of King Charles V of Spain. There was widespread opposition to the marriage, and this led to a rebellion that was only narrowly defeated. The rebellion had not been in Jane’s name and she took no part in it, but one of its leaders was Jane’s father, the Duke of Suffolk. Hundreds of the rebels were executed, Suffolk included.

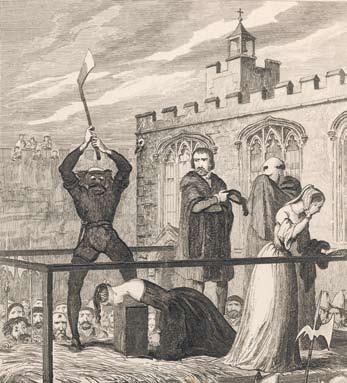

Now all prominent Protestants were in danger. When she refused to accede to Mary’s demand to convert to Catholicism, Jane’s fate was sealed. Mary ordered Jane’s execution. On 12th February 1554, Jane watched from a window as her husband was led away. A few hours later, Jane was standing at the same window as the horse-drawn cart returned with her husband’s body, the attendants carrying away the headless corpse and the head wrapped in cloth.

Jane had already been told that she was to be executed that day. She had dressed for the occasion, and had prepared herself. The guards called at her door, and Jane was led to the scaffold that had been erected on the green by the White Tower. She walked calmly to her place of execution, all the time reading from a book of prayers. Having climbed to the scaffold platform, she stepped forward to address the few people who had been allowed to attend.

“Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same,” she announced in a firm but nervous voice. “The fact, indeed, against the Queen’s highness was unlawful,” she continued, “and the consenting thereunto by me. But touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency…”

She knelt down and read Psalm 51, starting with the words, “Have mercy on me God … forget that I did not obey You.” When she had finished, she rose to her feet and gave her gloves and handkerchief to her lady-in-waiting, and her prayer-book to a soldier. It was the executioner’s job to blindfold Jane, but she stopped him and took the piece of white cloth in her hands. The executioner knelt before Jane and asked for her forgiveness, which she gave.

Then he told her to step forward, and she turned white as she saw the block. Jane said to the executioner, “I pray you to despatch me quickly.” She covered her eyes with the blindfold and tied a knot at the back of her head. Jane had prepared for this moment, determined to reach her end with dignity. But as Jane was about to kneel down and place her head on the block, panic took over as she became disorientated. She cried out, “What shall I do? Where is it?”

One of the attendants took hold of Jane’s arm and guided her; then he told her to kneel. As she rested her head on the wooden block, she stretched her arms forward and said quietly, “Lord, into Thy hands I commend my spirit.”

The axe was raised, and immediately came down. Nine days a queen, her death at the age of sixteen was the only memorable result. Killed by order of Queen Mary; but responsibility for Jane’s death lay firmly with her father-in-law and her father – they as good as murdered her.

The execution of Jane Grey

The execution of Jane Grey

MARY I

19 July 1553 – 17 November 1558

Mary came to the throne with the support of the vast majority of the population. Even Protestants, with some exceptions, supported her as the rightful heir almost as a matter of principle

– they would come to regret it.

Queen Mary’s maternal grandparents were Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, who united their kingdoms to become King and Queen of Spain. They were enthusiastic supporters of the Inquisition, the persecutors and murderers of thousands of Muslims and Jews. In England there were no Muslims or Jews; Mary’s victims would be the Protestants.

Her hatred of Protestants began early in life, as she grew up to believe that anyone who did not share her strict Catholic faith must be killed, preferably burned alive. When Henry VIII attacked the authority of the Pope, the Protestants sided with him. Nevertheless, Henry continued to burn Protestants as heretics, also burning Catholics who would not deny the supremacy of the Pope.

For Mary it was different, as she was not motivated by anger. In her case it was pure hatred, and that hatred was enflamed by the annulment of her mother’s marriage and the declaration of her own illegitimacy.

After Henry’s decision to seek the annulment, Mary was separated from her mother, and later forbidden even to write to her. Then Mary was forced to give her jewellery to Anne Boleyn, and ordered to give precedence to Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth, whom she was required to serve as ladyin-waiting. Everything conspired to turn Mary into an even more vengeful and nasty person.

Her first brush with death came in 1535. Henry and Parliament required everyone to swear the Oath of Succession recognising Anne Boleyn’s children as the heirs to the Crown, and implicitly that Mary was illegitimate. In addition, all those taking public or church office had to swear the Oath of Supremacy acknowledging that Henry was the supreme head of the Church, and implicitly that the Pope had no authority in England. Refusal to swear the oaths was treason, and that meant death.

Catherine of Aragon and Mary had agreed that they would not swear any such oath, and they fully expected to be executed. However, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was the son of Catherine’s sister and therefore Mary’s cousin. He was also King of Spain and Naples, Archduke of Austria and Duke of Burgundy. Charles was England’s natural ally against the French, and being Duke of Burgundy he ruled the Netherlands, which was the chief market for English wool. As a result, neither Catherine nor Mary was asked to take any oath.

Mary’s situation improved with the death of her mother and the execution of Anne Boleyn. Cranmer had annulled Anne’s marriage to Henry, so Elizabeth was now illegitimate and it was no longer necessary to protect her from Mary’s claims.

At Mary’s request, the Spanish ambassador sought an audience with Thomas Cromwell, the man with the greatest influence over the King. The ambassador asked Cromwell to speak to Henry, explaining that Mary wanted to be a faithful daughter and wished to return to court. Henry eventually agreed, but only on condition that Mary first signed a document repudiating the Pope’s supremacy and admitting that her mother’s marriage had been unlawful. Mary had fallen into a trap. Would she betray her mother?

A group of councillors travelled to see Mary with the document. She refused to sign it. The councillors were taken aback. They argued with Mary, they threatened her; but still she would not sign. As the councillors returned to court, they must have feared the effect of the King’s temper on messengers bringing unwelcome news. They were right about the temper, Henry flew into a rage. This time the messengers were spared; Henry’s anger was directed at Mary.

Treason, disloyalty, refusal to obey the King; any of them would have been enough. Henry knew only one way to deal with such behaviour – he sent Mary to the Tower. That was almost as good as a sentence of death, it only needed one more explosion of the royal temper.

The members of the Council were horrified; they feared war with the Emperor. Naturally, they did not dare to argue with Henry. Cranmer had more courage than the others, and he agreed to speak to the King. Diplomatically, Cranmer did not question Henry’s decision or pass on the Council’s views, he merely asked the King if Mary could be given a second chance to sign, and the exasperated Henry agreed.

Henry was furious with Cromwell for having suggested the reconciliation, and Cromwell wrote to Mary begging her to sign, otherwise both of them would be executed. The Spanish ambassador also urged Mary to sign, even if she was insincere. In the end Mary signed, at the same time writing to the Emperor asking him to obtain a dispensation for her from the Pope, allowing her to break her word. Six months later, Mary was back at court. Yet she would hardly have been nearer to death if the axe had been raised above her neck.

When her half-brother, Edward, succeeded to the throne, Mary retired to the countryside to avoid compliance with the new Protestant practices and prohibition of the Mass (the central act of Catholic worship). Mary’s insistence on continuing to celebrate Mass led to imprisonment for her servants, but Mary herself was not touched.

In later years, Mary would not reciprocate such merciful conduct to Protestants. She regarded her privilege not as a favour, but as a message from God that she was right and therefore all the more reason to burn the heretic Protestants.

After Edward VI’s death, the support of the people enabled Mary to overcome the Duke of Northumberland and his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey. Mary took the throne thirteen days after Edward’s death, Jane Grey’s father proclaiming Mary as queen to the joy of all Londoners.

Now that she was queen, an early consideration for Mary was the succession, and that meant marriage. As a princess, there had been several possibilities, but none had proceeded because of her father’s refusal to provide a large dowry, Mary’s reluctance and the fact that she had been declared illegitimate. Soon to be formally legitimised, and now a wealthy woman, she was, however, 37 years old and no great beauty. Fortunately, Emperor Charles’s son Prince Philip of Spain was available, as his wife (and cousin on both sides) had died shortly after giving birth to a deformed son (inbreeding meant that Philip had only six great-great-grandparents instead of the usual sixteen). Mary had no interest in a man eleven years younger than her, nor indeed in any man as she found the idea of sex abhorrent. But despite her feelings, she was prepared to do her duty, and she was eager to provide an alternative successor to her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth.