Ash: A Secret History (94 page)

She touched him.

The body flopped over on to its back.

“Godfrey?”

She knelt up, water streaming off her. Blood and filth soaked her clothes. The stench of the sewer dizzied her. The light from above dimmed, the crackling roar diminishing, the fire finding nothing more to burn than stone.

She reached out a hand.

Godfrey Maximillian’s face stared up at the curved, ancient brick. His skin was pink, in the firelight; and where she touched his cheek he felt icy cold. His chestnut beard surrounded lips just parted, as if he smiled.

Saliva and blood gleamed on his teeth. His dark eyes were open and fixed.

Godfrey, still recognisably Godfrey; but not half-drowned.

His face ended at his thick, bushy eyebrows. The top of his head, from ear to nape, was splintered white bone in a mess of grey and red flesh.

“Godfrey…”

His chest did not move, neither rise nor fall. She reached out and touched her fingertip to the ball of his eye. It gave slightly. No contraction moved his eyelid down. A small, cynical smile crossed her lips: amusement at herself, and how human beings hope.

Am I really thinking, with his head caved in like this, that he might still be alive?

I’ve seen and touched dead men often enough to know.

His mouth gaped. A trickle of black water ran out between his lips.

She put her fingers into the unpleasantly warm and jellied mess above his broken forehead. A shard of bone, still covered with hair, gave under her touch.

“Oh, shit.” She moved her hand, cupping it around his cold cheek, closing the sagging, bearded jaw. “You weren’t meant to die.

Not you.

You don’t even carry a sword. Oh, shit, Godfrey…”

Careless of his blood, she touched her fingers to his wound again, tracing the dented bone to where it splintered into mess. The calculating part of her mind put a picture before her inner eye of Godfrey falling, broken rock falling; water, impact; heavy masonry shearing off the top of his skull in a fraction of a heartbeat, dead before he could know it. Everything lost in a moment. The man, Godfrey, gone.

He’s dead, you’re in danger here, go!

You wouldn’t think twice, on the battlefield.

Still she knelt beside Godfrey, her hand against his face. His cold, soft skin chilled her to the heart. The line of his brows and his jutting nose, and the fine hairs of his beard, caught the last light from the flames. Water ran off his robes and pooled on the brickwork: he stank, of sewerage.

“It isn’t

right.

” She stroked his cheek. “You deserve better.”

The utter stillness of all dead bodies possessed him. She made an automatic check with her eye – does he have weapons? Shoes? Money? – as she would have done on a stricken field, and suddenly realised what she was doing, and closed her eyes in pain and breathed in, sharply.

“Sweet Christ…!”

She rose up on to her haunches, crouching on her toes, staring around in the water-rushing darkness. She could just make out the white glimmer of his flesh.

I would leave any dead man upon the field, if there was still fighting going on; would – I know – abandon Robert Anselm, or Angelotti, or Euen Huw; any of them, because I would have to.

She knows this because she has, in the past, abandoned men she loved as well as she loves them. War has no pity. Time for sorrow and burial afterwards.

Ash suddenly knelt again, thrusting her face close to Godfrey Maximillian, trying to fix every line of his face in her mind: the wood-brown colour of his eyes, the old white scar below his lip, the weathered skin of his cheeks. Useless. His expression, his spirit, gone, it might have been any dead man lying there.

Black clots of blood rested in the splintered bone of his forehead.

“That’s enough, Godfrey. Joke’s over. Come on, sweetheart, greatheart; come on.”

She knew, as she spoke, the reality of his death.

“Godfrey; Godfrey. Let’s go home…”

Sudden pain constricted her chest. Hot tears rimmed her eyes.

“I can’t even bury you. Oh, sweet Jesus,

I can’t even bury you.

”

She tugged at his sleeve. His body did not move. Dead weight is dead weight; she would not be able to lift him, here, never mind carry him with her. And into what?

The water rushed and things rustled in the darkness around her. The rift above was a pale, rosy gap. No noise came down from the ruined halls above, now.

Under her feet, the earthquake shuddered again.

“You killed him!”

She was on her feet before she knew it, shrieking up into the darkness, spittle spraying from her mouth in fury:

“You killed him, you killed Godfrey,

you killed him!

”

She had time to think,

When they spoke to me before, there was an earthquake.

And time to think, ‘

They’ didn’t kill him. I did. No one is responsible for his death except me. Ah, Godfrey, Godfrey!

The old brickwork shook under her feet.

I’ve been a soldier for five or six summers, I must be responsible for the deaths of at least fifty men, why is this different? It’s

Godfrey

—

Voices spoke, so loud in her mind that she clamped her hands over her ears:

‘

WHAT ARE YOU

?’

‘

ARE YOU ENEMY

?’

‘

ARE YOU BURGUNDY

?’

Nothing physical could block it. Her lip bled where she bit it. She felt a great vibration, the ancient bricks grinding together beneath her feet, mortar leaking out in dust and powder.

“Not my voice!” she gasped, lungs hurting. “You’re not my voice!”

Not

a

voice, but

voices.

As if something else spoke through the same place in her – not the Stone Golem, not that enemy: but an enemy somehow behind the Visigoth enemy, something huge, multiple, demonic, vast.

‘

IF YOU ARE BURGUNDY

,

YOU WILL DIE

—’

‘—

AS IF YOU HAD NEVER BEEN

—’

‘—

SOON

,

SOON DIE

—’

“Fuck off!” Ash roared.

She dropped to her knees. She wrapped her fists in the soaking wet cloth of Godfrey’s robes, pulling his body to her. Her face turned up sightless to the dark, she bellowed, “What the fuck do you know about it? What does it matter? He’s dead, I can’t even have a mass said for him, if I ever had a father it was Godfrey, don’t you

understand?

”

As if she could justify herself to unknown, invisible voices, she shouted:

“Don’t you understand that

I have to leave him here?

”

She leapt up and ran. One outstretched hand thumped the curved wall of the tunnel, grazing her palm.

She ran, the touch of the wall guiding her, through the darkness and the stone, through after-shocks of earthquake; into the vast and stinking network of sewers under the city, Godfrey Maximillian left behind her, tears blinding her, grief blinding her mind, no voice sounding in her ears or her head; running into darkness and broken ground, until at last she stumbled and came down on her knees, and the world was cold and quiet around her.

“I need to know!” She shouts aloud, in the darkness. “Why is it that Burgundy

matters

so much?”

Neither voice nor voices reply.

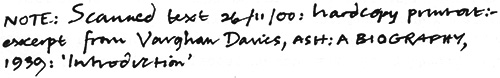

Message: #177 (Anna Longman)

Message: #177 (Anna Longman)

Subject: Ash

Date: 26/11/00 at 11.20 a.m.

From: Ngrant@

Anna –

We can’t GET to the offshore site. The Mediterranean is stiff with naval helicopters over the area, as well as surface ships. Isobel is off again talking to Minister ██████: I don’t know what, influence she can bring to bear, but she *must* do something!

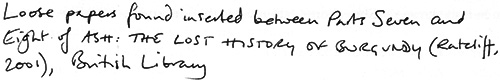

Forgive me, I haven’t even had time to tell you that your scanned-in text of the Vaughan Davies ‘Introduction’ came through as machine-code. Could you possibly try again in a different format? Did you talk to your bookseller friend, Nadia? Does she have any more information about this house clearance in East Anglia? As far as I am aware, Vaughan Davies died during the last war – this is a son or daughter of his, perhaps?

The way I’ve been moving around, it’s no wonder that you couldn’t get the file through to me. I’m back on Isobel’s machine now, working on the transferred FRAXINUS files, on the on-going translation, while we wait. I’ve been slowed down, obviously – you’ve nearly caught up with what I’ve completed.

As far as I can discover, no one has cracked Isobel’s encryption, so I feel free to tell you that the last two days have been absolutely *bloody*.

While Isobel’s team are perfectly amenable people, they’re under considerable stress; we spend our time sitting around in the tents – with them running analysis on what data they have been able to collect, and playing around with image-enhancers for the underwater details – Roman shipwrecks, mostly.

Anna, this isn’t the MARY ROSE, there may be a whole new level of mediaeval technology down there on the seabed, that we haven’t previously suspected the existence of!

Sorry: when I come to splitting infinitives, I know I’m distressed.

But there may be ANYTHING down there. Even – dare I say it – even, perhaps, a fifteenth-century GOLEM-POWERED ship?

Is there anything *you* can do, Anna? Have you any media contacts which could put pressure on the government? We are losing a priceless archaeological opportunity here!

– Pierce

Message: #118 (Pierce Ratcliff)

Message: #118 (Pierce Ratcliff)

Subject: Ash, media

Date: 26/11/00 at 05.24 p.m.

From: Longman@

Pierce –

I think I got the text file through to you this time. Please confirm.

I can’t promise anything, but I’m going to a social do tonight, at which will be an old boyfriend who now works for BBC current affairs. I’ll do what I can to suggest more notice should be taken of this affair.

This interference is INTOLERABLE. Surely it’s got to become a cause celebre?

Hang in there!

– Anna