Ash: A Secret History (222 page)

10

– [I find myself in agreement with Vaughan Davies’s supposition in the second edition of the ‘Ash’ texts (published 1939), and can do no better than quote it:

‘The oddities of religion apparently practised among the fifteenth century cohorts of Ash bear no resemblance to contemporary Christian practice. A more robust age – indeed, an age less in imminent need of divine protection than our own – can afford religious satires which we should, perhaps, deem blasphemous. These scurrilous representations (which occur only in the Angelotti manuscript) are Rabelaisian satire. They are no more intended to be read as fact than are descriptions of the Jewish race poisoning wells and abducting children. The whole matter is a satire against a papacy which was, by the 1470s, not at all beyond reproach; and shows the feelings which would, in the next century, explode into the Reformation.’]

11

– [Neither women, nor soldiers who were not officers, were permitted to be present at the Mithraic mysteries.]

12

– [In

AD

1450.]

13

– [Not the fish. In heraldry, a five-pointed star.]

14

– [Murrey: a mulberry or reddish-purple colour.]

15

– [With

rosbif

,

goddam

is a contemporary nickname for the English, at that time popularly supposed to be very foul-mouthed.]

16

– [4 May 1471: Prince Edward, the only son and heir of King Henry VI, is killed in battle with Edward of York (afterwards King Edward IV of England) at Tewkesbury. Henry VI dies soon after, under suspicious circumstances.]

17

– [‘Oxenford’ is one of the contemporary versions of ‘Oxford’.]

18

– [Seven years after the actions narrated in the ‘Ash’ texts, Richard of Gloucester is crowned King of England, as Richard III (1483-1485).]

19

– [Duke Charles of Burgundy, like his forefathers – Philip the Bold, John the Fearless and Philip the Good – was known to his people by a cognomen. Téméraire has been subsequently translated, according to taste, as ‘Charles the Bold’ or ‘Charles the Rash’.]

20

– [‘Dickon’ is the short, affectionate form of ‘Richard’.]

21

– [In point of fact, these events happened exactly as narrated here, but some eight years afterwards, in 1484. During the period covered by these texts, the Earl of Oxford remained a prisoner in Hammes castle. I suspect a chronicler of adding Oxford to the text, probably no later than 1486.]

22

– [Some sources give a figure of 400 men.]

23

– [This is accurate. The English King, Edward, offered pardons to the men, but to Oxford and his brothers, only their lives. Oxford was incarcerated in Hammes shortly afterwards.]

24

– [In 1485, by winning the Battle of Bosworth for the then ‘Welsh milksop’ Henry Tudor, Oxford – put Henry VII of England on the throne (1485-1509). Whether that is ‘a better man’ has long been a subject of debate.]

25

– [Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, and Margaret of Anjou, wife to Henry VI of England; these inveterate noble enemies, having in 1471 spent the past fifteen years on opposite sides of the royal wars, were reconciled to an alliance by John de Vere.]

26

– [Garden.]

Part Five:

1

– [‘Affinity’ – For a feudal magnate, this would include his dependent lords, maintained in his livery; his political allies among other feudal lords; and any commercial interests dependent on him for grace and favour.]

2

– [Born in Dijon in 1433, Duke Charles was in fact 43 at this time.]

3

– [A legendary female knight, notably popularised in Ariosto’s

Orlando Furioso

(1516).]

4

– [Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou had only one son, Edward, killed at the battle of Tewkesbury. Any claim of the Lancastrians to the English throne thus devolved to more tenuously related men (ultimately to Henry Tudor, whose Welsh grandfather had married the widow of King Henry V). The Yorkist Edward IV, meanwhile, held the throne.]

5

– [In fact, Charles had registered his formal claim to the English crown in 1471, five years previous to this, but took no further action over it before his death.]

6

– [The ‘

uqda

was carried by a

nazir

’s troop of eight men.]

7

– [The original text has ‘fortuna imperatrix mundi’.]

8

– [Philippe de Commines or Commynes (1447-1511), historian and politician who first served the Burgundians, then betrayed them for the French. He became advisor to Louis XI four years previously, in

AD

1472.]

9

– [1465.]

10

– [The text gives us ‘iuventus’, referring to young men between, say, sixteen and twenty; in our terms, these are teenagers.]

11

– [St Barbara, a Roman saint previously appealed to for protection against being struck by lightning, was adopted as the patron saint of gunners, presumably on the grounds that one explosion is very like another.]

12

– [The eleventh century Dame Trotula of Salerno was a clinician, and the author of

Passionibus Mulierum Curandorum (The Diseases of Women)

, among other medical works. She was regarded as one of the foremost medical authorities of the mediaeval period. Other ‘mulieres Salernitanae’ or women physicians were also trained in Salerno, but this practice may have ceased by the fifteenth century.]

13

– [Since most combatants are right-handed, close combat battles tend to rotate anti-clockwise.]

14

– [Wearing duplicate armour and livery.]

15

– [Small field cannon.]

16

– [No relation.]

17

– [In mediaeval military terms, a ‘battle’ is a unit of men, rather than a specific combat. Mediaeval armies were often divided into three battles or large units, for fighting.]

18

– [The personal device of the Earl of Oxford.]

19

– [Used by Roman, Byzantine and Arab cultures, in both naval and siege warfare, the exact constituents of ‘Greek Fire’ remain unknown, although naphtha, sulphur, oil, tar, saltpetre and pitch have been suggested. Its nature as a terror weapon, however, is well recorded in history.]

Part Six:

1

– [Given the date of

AD

1476, the text cannot be referring here to the original Phoenician settlement of Carthage, or to Roman, Vandal or Byzantine Carthage. Since the culture is not Islamic, this must be a reference to my presumed Visigoth settlement, possibly at or near the same geographical location, and named ‘Carthage’ for that reason.]

2

– [The Latin has ‘upper body strength of a sword-user’; this is the nearest modern comparison.]

3

– [??? – PR. This is completely baffling! The

Reconquista

involved Spanish Christian forces driving out the remaining Arab cultures from Spain (after the Arab conquest and settlement begun in

AD

711), a process completed in

AD

1492, some sixteen years after the events supposedly depicted in the ‘Ash’ texts. I can only suppose complete textual corruption here. After five hundred years it is impossible to guess what the ‘Fraxinus’ chronicler actually meant.]

4

– [This is obviously either a folk memory of the supreme Carthaginian sea-power in the Mediterranean around the time of the Punic Wars (216-164

BC

), or of the Vandals’ dominating navy in the 6th century

AD

.

A very similar passage appears in ‘Pseudo-Godfrey’; indeed it may have been copied into this. If the author of ‘Pseudo-Godfrey’ was a monk, then he would have access to preserved Classical texts, which he has here conflated with the mediaeval myth of the Sea-Serpent to depict a mythical segmented ‘swimming ship’, and a ‘paddle-wheel’ powered vessel. Mediaeval authors are prone to this. We can assume Ash actually saw a double- or a triple-oared galley, rowed by Carthaginian slaves.]

5

– [Since this is used for street lighting, this would appear (despite the text’s use of the same name) to be a variant of Greek Fire – perhaps using only the ingredient naphtha, which receives its name from the Arabic

al-naft

, and has a later history of use for this purpose in industrial England.]

6

– [Possibly a Christianised version of the Carthaginian goddess, Tank, to whom babies were sacrificed.]

7

– [This, and another similar reference, are additions to the original manuscript. Even were they not inscribed marginally in different handwriting, context would prove as much: the role of Rattus Rattus in carrying the ‘plague flea’ was not realised until 1896. I suspect a Victorian collector read this document at some point in its existence; a descendant, perhaps, of the man who wrote ‘Fraxinus me fecit’ on the outer sheet in the 1700s.]

8

– [Possibly China. By the physical description in the text, this is not

Rattus Rattus

, the Black Rat, but

Rattus Norvegicus

, the Brown Rat, which is Asian in origin.]

9

– [Ash’s concern with the destructive capacity of rodents is original to ‘Fraxinus’, and must have been a similar problem for all army commanders.]

10

– [Presumably ‘cervix’]

11

– [Otherwise

De Re Militari

. The 1408 edition, made on the orders of Lord Thomas Berkeley?]

12

– [The mediaeval medical theory of humours attributes health to a balance of the sanguine (dry), choleric (hot), phlegmatic (wet) and melancholy (cold) humours in the body. Ill-health is a predominance of one over the others.]

Part Seven:

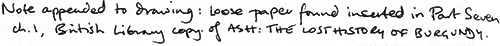

1

– [Young pike.]

2

– [The geography of Visigothic Carthage, as depicted in the ‘Fraxinus’ manuscript, does not appear to wildly contradict the known archaeological facts. The compass directions are a little off, but there is more often than not a mismatch between site and chronicle in archaeology.

In fact, there were two enclosed harbours behind an isthmus: the commercial harbour and the great naval shipyards. They were a feature of what we may call Liby-Phoenecian, or Carthaginian, Carthage; as was the Byrsa, an enclosed hilltop citadel within the main city itself. The streets were, indeed, stepped.

Close to this original site, Roman Carthage added other features, including water-storage cisterns, aqueducts, baths, an amphitheatre, and many features of civilised life; as well as their own great naval shipyards.

[Anna – here’s my rough aerial sketch of the ruins of present-day Carthage, and a proposed geography of 15c Visigoth Carthage.

I’ve included a possible new Visigoth harbour (which, like areas of the Roman/Carthaginian ones here, and the one at Leptis Magna, may have silted up in the interim).

The exact site of the Byrsa or walled hill during the 15c is conjectural, based on textual evidence.

Pierce]

3

– [‘God protect you’.]

4

– [‘Green Christ, Christ Emperor’.]

Other books

Like Fire Through Bone by E. E. Ottoman

City of Night by Michelle West

The Boys Are Back in Town by Christopher Golden

Chilled (A Bone Secrets Novel) by Elliot, Kendra

The Art of Mending by Elizabeth Berg

Bee Season by Goldberg, Myla

Beastly Desires by Winter, Nikki

The Riddle at Gipsy's Mile (An Angela Marchmont Mystery 4) by Benson, Clara

Little Bird of Heaven by Joyce Carol Oates