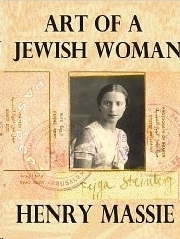

Art of a Jewish Woman

Read Art of a Jewish Woman Online

Authors: Henry Massie

Tags: #History, #World, #World War II, #Felice Massie, #Modernism, #St. Louis, #Art, #Eastern Europe, #Jewish, #Poalnd, #abstract expressionism, #Jewish history, #World Literature, #modern art, #Europe, #Memoir, #Biography, #Holocaust, #Palestine, #Jews, #Szcuczyn, #Literature & Fiction, #art collector

Art of a Jewish Woman

The True Story of How a Penniless Holocaust Escapee Became an Influential Modern Art Connoisseur.

BY

Henry Massie

booksBnimble Publishing

New Orleans, La.

Art of a Jewish Woman

The True Story of How a Penniless Holocaust Escapee Became an Influential Modern Art Connoisseur.

Copyright 2012 by Henry Massie

Cover by Nevada Barr

ISBN: 978-161750-991-9

All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First booksBnimble Publishing electronic publication: March 2012

Digital book(s) (epub and mobi) produced by: Kimberly A. Hitchens,

[email protected]

Art of a Jewish Woman

And what a vibrant voice! It’s like a stream of water that fills your mouth.

Frederico Garcia Lorca,

Yerma

, Act 1, Scene 2

Why would anyone want to write about me? I am just a girl from a poor little village in Poland. But I had so many adventures. I can’t believe all the things that happened to me. Sometimes truth is better than fiction because it is more unbelievable.

Felice Ozerovicz Massie

PART ONE. FRANCE

Language of Love

The train with four wooden carriages stuttered to a halt at the Lebanese crossing into Palestine near noon on a September day in 1935. Felice and her companion stepped into the sun, feeling the intense heat, tasting the sting of salt from the Mediterranean Sea to the west. For a moment a breeze from the mountains on the east brought a hint of freshness. The wild grass along the tracks was burnt golden. Everything was seared, scorched, except for the flowers in the border station’s window planter boxes. Dust hung in the air from a gravel road that paralleled the tracks.

Inside the stone building, a British officer examined passengers’ travel documents and passports. When Felice’s turn came, the crisply uniformed colonel looked at her bare shoulders and her short beige and cream linen dress. She was beautiful, petite, just five feet tall, her long black hair in a chignon, lipstick and eye liner carefully applied. Then he looked at the man by her side. A marriage certificate issued the day before by a rabbi in Beirut said they were husband and wife. The man looked malnourished. He had a red beard and long ear-locks, and large spectacles covered his face. His black suit was all dusty, and his head was covered with a large Hassidic black fedora. The couple did not speak to each other.

Felice presented her documents—a Polish passport with an exit stamp from Marseilles dated two weeks earlier, and an entry stamp into Lebanon dated the week before, plus her French university diploma. She was twenty-five and had just graduated from the University of Nancy, France, with a doctor’s degree in dental surgery from the medical school. The colonel knew the deception: more and more Jews were using fictive marriages to make their way into Palestine as Hitler’s Nazis spread anti-Semitism into Poland and closed off opportunities for Jews to make a living.

The colonel was under orders to do his part at the border to stop the flow of illegal immigrants into Palestine, which had been a British mandate since the end of World War I. There was a quota for Jews, intended to minimize conflicts with the Arab population. He asked Felice first in English, which she didn’t know, then in French, “Are the two of you married?”

“Yes, of course,” she answered him.

“What language do you have in common?” he continued, probing the ruse.

But Felice and her newly certificated husband had no language in common—he spoke Arabic and Hebrew, and she Polish, French, German, Yiddish, and some Russian. “The language of love,” she said in perfect melodious French, not missing a beat, flirting with the colonel.

His rejoinder: “Tomorrow is my day off. I will meet you for dinner at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem.” She smiled at him. He stamped her entry visa!

The train steamed south. Sometimes it was within sight of the bright blue Mediterranean sand dunes bordering the tracks, sometimes inland among marshy wasteland, sometimes passing through orchards and citrus groves on land reclaimed from swamps by settlers from Russia and Poland. Occasionally there were Arab villages with stone houses and crops and fruit trees laid out in neat squares marked by low stone walls. Every once in a while cypress trees stood pencil thin, almost black like sentinels in rows along the edge of a field or road.

The carriage was humid and warm, windows pushed open to let in the salty air. A tall, skinny, coal black porter from the Sudan in a long white robe passed through the corridor with a tray of sweets, glasses, and a copper urn with mint tea. The train click-clacked and swayed from side to side. From her purse Felice took the letter her father Moses had sent her in France. Writing from their village in Poland, he had given her meticulous instructions, which she had read over and over and memorized in case she lost the letter. She was to go to Jerusalem with the man her father arranged for her to marry, and he would provide her with lodging and a job in return for the $200 her father had sent directly to him. The words and the train’s click-clack and side-to-side sway lulled her like a metronome into daydreams, back to France.

In her reverie, she stood on the dock in Marseilles bidding Samy farewell. They had driven down from Nancy to Marseilles the day before. They were standing on the jetty. She wore her other dress, the black shirtwaist one hemmed just below her knees. She could only afford two and this one had served for school and going out on winter evenings. She grasped her small, battered suitcase. Inside it were her dental instruments, rolled in a cloth instrument case, and the precious French diploma that would allow her to earn a living. Even in high heels she had to stand on her tiptoes to reach Samy’s lips when the boat’s horn sounded. They tried to force normalcy into sadness. But they couldn’t do it; the kiss was odd, not full, cautious.

“I will write you. I will visit you. You will meet someone and have six children,” he said.

“I will have two children. One because I want children and a second to be safe in case something happens to the first. I will name the first one after you.”

“We will write. I will visit you in Palestine.”

“I will try to find a telephone when I am settled and call you.”

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. She thought they would marry when she graduated and live together in Neufchateau-des-Voges, not far from Nancy, not far from the Alps. Samy, a recent graduate from the medical school, had opened a practice there, and Felice planned to start a dental surgery practice. Samy—from Bucharest, Romania—was a legal immigrant with a right to work in France because of a French-Romanian agreement. Once married, Felice too could stay and obtain a work permit. Without marriage to a legal resident, Poles could only study in France and had to depart after graduation. But then Samy became ill, and having children was no longer possible.

The boat horn sounded again, louder, more peremptory, and Felice ascended the gangway slowly. She took a few steps and looked back. Samy had his handkerchief out to wipe away tears. Felice, too, started crying and bent her head down and pushed forward almost to the top of the gangway before she turned around again, ready to abandon the plan and rush back to Samy. He was gone. She took out her handkerchief and composed herself as she stepped onto the deck.

Aboard the large ship—the first she had ever been on—she settled into its rhythms of meals and port calls. She sunned on the deck and let her sadness ebb away. In Genoa and Naples she watched people disembark and embark and saw train cars shuttle on rail sidings set into cobblestones and pushcarts laden with luggage move to and from the boat. She had only the little money Samy gave her to get to Jerusalem. Her ticket paid for meals and a second-class berth.

On the deck she met Emil Bocktor, a psychiatrist from Egypt returning home to Alexandria. They spoke French and soon became friends. He took her dancing and into the ship’s first-class restaurant, where the food was better. When the ship stopped in Piraeus, the port of Athens, Felice and Emil visited the Parthenon.

She knew about the Parthenon even though she was from a tiny, poor farming village on the Polish-Russian border, a town named Szczuczyn (pronounced and sometimes spelled Stutchin). She had been a gifted student, and her father sacrificed what he had to send her away to school for a classical education. On top of the hill in front of the Temple of Athena her face glowed with excitement and her words spilled out as she explained the white marble ruins of ancient Greece, its art, history and mythology to Emil. Soon a crowd formed around her, and she lectured to a score of people like an official guide. Her friend urged her to change her plans and go to Alexandria with him.

“My family would so like to meet you. The chauffer will pick us up at the port.”

Felice fingered the letter from her father in her purse and said, “I wish I could accept your invitation but it isn’t possible. I have to be in Beirut in two days.”

In Beirut she went to the Hotel Tel Aviv to wait for the arrival of her intended husband from Jerusalem, the stranger now seated next to her on the train. The hotel was a three-story, nondescript, whitewashed plaster building. Only the very small wrought iron balconies in front of blue-shuttered windows gave it some life. It was really a dank transit station on an underground railway for Jews making their way into Palestine. The father of the Sephardic family that owned the hotel wore a big red fez and a long gown. He spoke in French with Felice, but all around were the strange sounds of Arabic, which she had never heard before.

Alone in her bedroom the first night, she thought that the gauzy white cotton

moustiquaire

over her bed was for decoration, not to protect her from mosquitoes. She was so hot she tore it off. She had never been in such a climate. Mosquitoes came from a pool of stagnant water beneath her window and attacked her in the night. She thought that bed bugs were eating her up. She longed for France.

But there was recompense: the proprietor’s son, Pariente, drove her along the Corniche and took her to the beach. He was falling in love with her. On a large paddle board they drifted lazily offshore on a gentle tide, and Felice uncovered her breasts as other European women did to tan themselves.

Three days later the fiancé arrived, dressed in the same dusty black suit he now wore on the train. He kept his eyes cast down, as if afraid to look at her. When she first saw him, she was appalled and said to herself, “What has my father done to me?”

Pariente too was feeling deceived after spending three days with Felice, feeling she had led him on shamelessly. His role was now reduced to shepherding the bride and groom to the synagogue, and he refused to look at her further. In the rabbi’s study, Felice paid the rabbi his fee and a few more dollars for the precious marriage document. Felice Ozerovicz became Mrs. Steinberg.

In the evening of her wedding night, when Mr. Steinberg shuffled uneasily beside her after dinner in the hotel parlor, Felice told him she had to study. There was no question that she would keep her room to herself. She pulled and knotted the mosquito netting firmly around the bed. “My husband can go to sleep God knows where,” she told herself.

The train bucked and slowed. They were approaching the station in Haifa. She could see the port. Small, pastel-colored houses rose up the hills that formed a half moon around the bay. In the station were signs and advertisements in Arabic and Hebrew. Sometimes, like an afterthought, there were signs in English. Felice knew the Hebrew alphabet already and started using a dictionary she had purchased in Beirut to learn words, asking her companion to pronounce them.

After Haifa the railway carriage fell back into its rhythm. There were two more hours until Tel Aviv, where they would change trains and climb the Judean Hills to Jerusalem. Felice began thinking about another rail journey she had made five years earlier in the fall of 1929, from her village to Warsaw, then through Germany to France. She was nineteen then and had graduated from boarding school in Wilno the spring before. She was starting her first year of university in Nancy.

Nancy, France

Then as now, she had only one suitcase, though bigger because she had packed a winter outfit to protect against the cold winds and snows that blew from the Alps. She had a dictionary on her knees as the train picked up speed after crossing the German border into France near Strasbourg. As soon as village signs appeared, she started looking up words in her French-Polish dictionary. French came quickly because she had studied six years of Latin and all the Latin classics beginning in middle school. She had outdone the Polish boys preparing to be priests. At the end of high school she won the Latin prize. The school offered her a job teaching Latin.