Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (47 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

of individual identity, with a rethinking of American politics. Much is unprecedented in its newness: the killer disease, the ozone hole, the alternative culture, the arrival of the Angel. But the old does not disappear: love and loyalty remain as a kind of human syntax that nothing can disrupt. Kushner closes his epic story with humor, tenderness, and visionary wonder. Roy Cohn, "in Heaven, or Hell or Purgatory," finds new work in the area of family law, defending God against the paternity suit that has been building over the centuries. Harper, airborne, is bequeathed a vision of human and planetary healing:

Souls were rising, from the earth far below, souls of the dead, of people who had perished, from famine, from war, from the plague, and they floated up, like skydivers in reverse, limbs all akimbo, wheeling and spinning. And the souls of these departed joined hands, clasped ankles and formed a web, a great net of souls, and the souls were three-atom oxygen molecules, of the stuff of ozone, and the outer rim absorbed them, and was repaired. (II.142)

This luminous parable counters the familiar Humpty-Dumpty story of plague's ravages, its systematic undoing of body, family, society, and planet. Blithely undoing the routine binaries of life/death, body/soul, even the tug of gravity itself, Kushner's epiphany repairs the ruptured membranes, those of the diseased creature and the polluted planet. And the still living Prior, who has refused the reactionary mission offered him by the Angel, delivers the final paean to life and politics, a vision of existence beyond plague:

This disease will be the end of many of us, but not nearly all, and the dead will be commemorated and will struggle on with the living, and we are not going away. We won't die secret deaths anymore. The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come.

Bye now.

You are fabulous creatures, each and every one.

And I bless you:

More Life.

The Great Work Begins. (II. 146)

Angels in America

completes my sequence of plague-texts by trumpet-ing forth in strident, often over-the-top ways, how richly the story of disease turns out to be a story of the culture at large. Prior's final words are to be taken literally: "You are fabulous creatures, each and every one," with emphasis placed on

fabulous,

on the amazingly colorful, variegated and storied existence of all

creatures

who live and love in bodies. Plague is the language of connection, connection now experienced as disease and death, but connection also as the very form, the gestalt, of eros and of politics, and Kushner is mapping a moment of American history when these forms are in crisis, when they are molting. The author's light shines backward to the shtetl and the Mormon pioneers, and it beams forward to the coming world where many of the old paradigms—Marxism, nuclear fam-ily, intact ozone layer, walking and behaving "straight"—no longer retain authority. But its most powerful illumination is on the present, the antics of a careening world ofFbalance, trying to reconcile its old beliefs with its new discoveries, experiencing the beauty, the horror, and the sheer power of the body at last placed on center stage, exposed as the driving force of the creature, requiring an ethos and a politics worthy of its needs and yet true to the older codes of decency and loyalty that are the West's irreducible, nonremovable ethical luggage.

Only art can tell the multifaceted story that Tony Kushner has wanted to tell. The reports of both the medical and the social sciences can tell us a great deal about the pathology, demographics, and even therapies for AIDS, but they do not take the measure

of creatures

who are,

each and every one, fabulous.

The scream goes through the house in Kushner's large-souled play, and we understand the house to be the American body politic and even the Judeo-Christian tradition. With humor, pathos, and nonstop brilliance, Kushner takes the stark plague narratives of the past and converts them into a story of our time, our place.

CHAPTER FIVE

SAYING DEATH

It is not because other people are dead that our affection for them fades; it is because we ourselves are dying.

— MARCEL PROUST,

Remembrance of Things Past

I heard a Fly buzz

—

when I died

—

— EMILY DICKINSON

AVOIDING DEATH

Why speak about death? Most of us spend our lives trying to forget about it, unless we happen to be either undertakers or doctors or professional philosophers. Or sick. Or depressed. The seventeenth-century French philosopher Pascal, who was obsessed with these matters, said that everyone else should be too, concluding that our routine avoidance of the thought of death is the oldest human dodge in history. Our essential dignity, he held, consists in pondering our end, and here is what he then saw: "Imagine a number of men in chains, all under sentence of death, some of whom are each day butchered in the sight of others; those remaining see their own condition in that of their fellows, and looking at each other with grief and despair await their turn. This is the image of the human condition" (165). These penitential arrangements constitute our bedrock truth, Pascal claimed, and we need to face up to them. The classic rejoinder to such a grim injunction was provided by Voltaire, a century later, when he charged Pascal with being at once morbid and useless, claiming that life itself deserves our attention, rather than how it must come to a close. Voltaire had no time for such ultimacies and metaphysics, and he had a point.

Pascal approached death as a religious philosopher, seeking to make his readers embrace Christianity. Voltaire the pragmatist focused on the social tasks that await us in life. I want, in this chapter, to champion Pascal, but to do so on strictly secular grounds: thinking about death, discovering how artists and writers have thought about death, represented death, is exciting and instructive. The excitement is at once intellectual and imaginative: how does the mind make sense of death? of dying? And, how can we imagine, visualize these issues? Responses to this inquiry are stunningly varied, and therein lies what I have called "instruction." Thinking about death and dying brings

life

into focus as nothing else can.

Art's testimony on these matters differs utterly from religious doctrine, in that it seeks illumination rather than conversion: "illumination," the intensifying of

light,

so that we begin to

see

all that these matters entail, so that the elemental darkness that many of us construe death to be is transformed into something luminous and large. I am Voltairean here, in that my sights are indeed on this life, this side of the grave, and I contend that the renditions of death and dying in literature and art are food for the living.

I began by saying that most of us avoid thinking about death, but is this possible? Is our thinking itself not saturated with death? Consider how profoundly death informs all our notions of understanding, wisdom, education, and the like. I do not mean some kind of memento mori, but rather the view that death is hardwired in many of our most basic concepts. Wallace Stevens asks, rather wonderfully, in his poem "Sunday Morning," "Is there no change of death in paradise? / Does ripe fruit never fall? Or do the boughs / Hang always heavy in that perfect sky, / Unchanging, yet so like our perishing earth, / With rivers like our own that seek for seas / They never find, the same receding shores / That never touch with inarticulate pang?" (9). Ripe fruit does fall here on earth, our "perishing earth," just as seeds grow into the fruit that ripens, and rot follows upon fallen fruit. Indeedjust as human development itself is inherently a mobile affair, a linear temporal trajectory that

must move from infancy and childhood on to maturation and death. All notions of understanding and value are deeply organicist in nature, tied to a view that recognizes the birth-death tandem as the structure and course of all living things, including wisdom and, perhaps, love.

Consider those cliched images we have of heaven as some stage set of clouds in a blue sky, bathed in eternity, immutable and unchanging; nothing in life could prepare us for such a realm, a place where the boughs hang always heavy, and this time-free zone seems peculiarly di-mensionless, a place without waxing or waning, hence a place where notions such as expectation, desire, and "becoming" are unthinkable. Stevens's famous line "Death is the mother of beauty," properly caps this line of reasoning, not only because the destruction that is death gives beauty its value, but because death truly

mothers

our view of life by installing the very processes that make meaning possible. These are the insights proper to poetry, coming to us as images of things we know— fruit, boughs, rivers, seas—and helping us to a larger sense of death's ubiquitous rule.

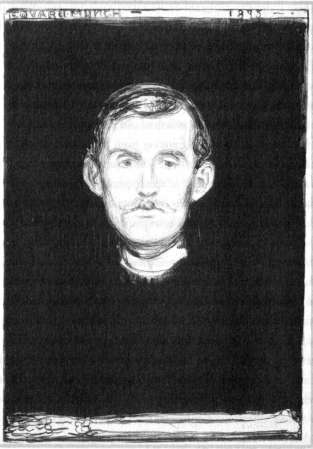

While death is the ever-present backdrop against which life achieves focus and definition, ordinarily, mercifully, we do not see this backdrop. Sometimes, however, via art, we do. I think that Edvard Munch's

Self-Portrait with Skeletal Arm,

done in 1895 at the height of his physical and artistic powers, brings this home to us. The elegant, refined face of the artist emerges magically from the brilliant black background—Munch had just learned in Paris how to produce this gleaming, dazzling jet black—and I used to regard this lithograph as a creation myth: the birth of the self as it breaks through the prior nothingness. I now think Munch is trying to position the precarious, miraculous reality of life and self within its ultimate matrix: death. "Who am I?" he seems to be asking, and we see the answers, in three distinct registers: as letters and numerals, "Edvard Munch, 1895"; as two-dimensional figure, the one whose face the painter both saw in the mirror at that precise moment and also had the genius (then, in 1895, in his prime) to convey/construct in his art; but also as skeletal arm, not

Self-Portrait with Skeletal Arm,

Edvard Munch, 1895.

merely the skeleton within the flesh, but rather a material index of who he will be. It is all there: the blackness of Nothing prior to his life, the moment of splendor in/through his work, the fate of death that is inescapable.

This lithograph attempts nothing less than a form of cubist portraiture, a way of representing the human being

in time,

and it thus has the pathos of all death-inscribed phenomena, wise about the evanescence of its human subject (the physical Munch is now, as you read, a skeleton),

no less wise about the permanence of its medium (you are looking at this representation now; it cannot die), and immensely moving because it has captured just this dialectic of life, death, and art.

Death, our oldest fact of life, is central to discourses of religion, philosophy, biology, anthropology, and much else that is less self-evident, including politics and art and all creative endeavor. Moreover, it has long been known that religion, science, and literature have constructed stories to make sense of death, ranging from forms of spiritual afterlife and genetic survival, on to fables of reincarnation, moral achievement, and spiritual reward. Almost all of these spend as little time as possible with death itself, but rather move on to disguised life-scenarios, whether they take place in heaven, genetic arrangements, or history. Death as cessation, and dying as entropic fate of living creatures, are severe starting points for any kind of narrative, even though dying itself is a lifelong activity that does have obvious shape and form, as a casual glance at the old and not-so-old makes overwhelmingly clear. Artistic and literary performances both challenge and add to our database in this area by giving us accounts or even renditions that are sharply at odds with the biological ending that awaits us. To be sure, a poem or short story will not stop death, but it may well add furnishings and stock to the minds of those who will die. Above all, art's depictions of death and dying open what is closed, afford us imaginative toeholds and beachheads in campaigns that our bodies are fated to lose.

Hamlet, whose every reflection and meditation (including "to be or not to be") obsessively centers on mortality, refers to death as the "undiscovered country," and no one can disagree. Suicide, the prince muses, rushes us to a destination about which we can know nothing. Death is our common fate, but it has not been charted or mapped out. Hence, all writing about death is radically secondhand; we might even add: radically suspicious, because it is always the account of witnesses and bystanders, never the experience itself. Supposition, projection, and fantasy loom large here. And for those who do not trust literature in the first place, literary accounts of death must be particularly question-

able. On the other hand, scientific accounts of the cessation of life seem just as "external" and "locked out" as literary ones do. The body can be described in its agony and subsequent rigor mortis, but is this not just die shell? There is a vein of writing that deals with "out-of-body" experiences, and there are cases of patients who have been "at death's door," and have not only recovered but have left us accounts of what they saw there. But even this is, after all, both liminal and limited, a foretaste of the real thing.