Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (13 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

The Scream,

Edvard Munch, 1893.

way to all that is diseased and terrifying about modern life. Munch's figure on the bridge, shorn of all gender markings and psychological nicety, swaying frontally toward us with its terrible tidings, seeking feverishly to block its ears as its gaping mouth and ghoul-eyes fix upon us, personifies our most nightmarish notions of the modern era. That this piece has become a commercial, even "hip" icon today, seen in advertising and publicity, found on wrapping paper and greeting cards, appearing in graffiti on walls and under bridges, does not really diminish the virulence of the work. Munch has left us a record of this painting's genesis, how it began in a more meditative, melancholy symbolist form (with a gendered figure looking down into water), and how it

sought to give visual form to an earlier memory Munch had had about a sky suddenly blood red, "flaming clouds like blood and a sword," "and I felt as though Nature were convulsed by a great unending scream" (quoted in Eggum, 81).

The congruence between Munch's words and the title of my book hardly needs pointing out, and this painting illustrates to perfection the range of our issues. "A scream goes through the house," and we now see that the "house" is no less than the cosmos itself, the sea and sky worked up to paroxysmal fury as the human creature . . . utters? . . . hears? the great shriek. Here we see, as never before, the power of human feeling, the awesome agency it has acquired. We cannot determine if the environment is shaken by the human's anguish, or if the human is shaken by the environment's fury, but what we can hardly miss is that these two seemingly disparate realms—environment and subject, outside and inside—are now fused, and with this fusion disappear all the protective barriers and boundaries that customarily (mercifully) mark off self from world.

Proust once described a dying character in terms of someone who suddenly felt the monstrous force of gravity itself pulling the body into the grave, and something similar is happening here: the fundamental contract that preserves human equilibrium—I am I, and the world is the world—has been scandalously breached. The world is hemorrhaging, the dike has collapsed, the flood rushes in. If the origin of such fury is external, it suggests a demonic world, yet also a world become familiar to us in its outbreaks of earthquake, hurricane, and the like; if the origin of such fury is internal, it suggests a tempest of a different sort, a psychic, affective storm that cannot be weathered, with analogues such as seizure, stroke, and infarction. The bridge that should offer safe passage is a tilted, elongated affair, a plane you could slide off into the maelstroms that surround it. Bad news is everywhere in this painting. But the most insidious reading is that outside and inside are in horrible collusion, and once we entertain this view, we understand it to be the greatest threat of all. Is that not the core incapacity on show here? Nothing can

be kept "in" or "out." "Keeping" is a cultural myth, derived from fond notions of stability and control that make sense to those who are well.

Pain and sickness initiate us routinely into the maelstrom Munch has painted, even if we do not care to see our entry in such garish terms. In sickness, in old age, the body's circuits and channels play us false: obstructions can block pathways, fluids move where they shouldn't, the entire hydraulic, plumbing, and electrical arrangements go amok, the thermostat is off, the organs mutiny, viruses and bacteria invade, the immune system fails. This central drama of the human subject under siege, attacked from without and within, characterizes our somatic fate; it also has uncanny parallels with Munch's

Scream.

In studying Blake's poem "London," we saw that the "chartered Thames" is a lie, that the flow of elemental forces cannot be governed by law, political decree, or human will; we saw this most strikingly in the fateful return of the flow, in the form of blood that runs down palace walls. In

The Scream,

that blood is back. As the Ur-flow of human life, the corporeal Thames that each of us contains, the river that governs our life and death, it deserves place of pride in any depiction of actual somatic life.

Munch saw a bloodred sky, and we know from his correspondence that he agonized over this painting, agonized that he couldn't make a red that would make us feel indeed that we were looking at blood rather than paint. A work of art composed of real blood is hard to imagine, although doubtless some performance artists can manage it; but

The Scream

comes very close, I think, to realizing Munch's impossible desire, in that it is true to the law of flux, shows the human subject to be a sinuous flow of forces (energy, blood, paint, swirling lines) alike in nature to the force field that contains it. Everything is at the breaking point here: the subject vomits its anguish, the world convulses in a scream. Munch's painting is cardiac in the sense that it pulses over, washes away barriers and frames, inaugurates a regime of pure flux. As such, it reconfigures our place in the world, by erasing all customary contours: gender, nature/self, even painting/viewer. A new world is in sight.

One cannot imagine living very long in these precincts. Even Munch

has his periods of calm and respite. Yet, the power of

The Scream

clearly derives from the shock of recognition experienced by every viewer: this is the bedrock truth of pain and despair; these are our most naked arrangements. Munch has challenged conventional notions about our real whereabouts: our lives in bodies, our lives with one another, our position on the planet. His paintings set forth a new geography, and yet this geography is also very old, in that it confirms what we actually sense when we are in pain or gripped by feeling. In the last analysis, Munch's paintings are territorial; they construct a terrible homeland, enabling us to encounter vistas such as we have never seen but have always known.

PATHWAYS OF FEELING: BERGMAN'S

FANNY AND ALEXANDER

Flux—a state where things ordinarily considered separate, such as past/present, here/there, you/me, merge into each other—has been posited as the rival logic at work in Blake's poem, Baldwin's prose, O'Neill's drama, and Munch's paintings, flux understood as the collapse of boundaries and the emergence of a meshed condition that wipes out individual self-sufficiency. Feeling is the motor force in all this, feeling now revealed as the supreme mover in human affairs. Yet even these art forms remain, in some ultimate sense, static; they are turned mobile only by the reader/spectator's active involvement. After all, the poem or the story or the play sits still on the page. But could there be a form of art that embodies movement and flux direcdy? Dance is obviously one answer. But film is another. The "moving pictures" offer a unique means of representing this fluid logic, and the final part of this chapter will be devoted to the work of Ingmar Bergman, who, in his great final opus,

Fanny and Alexander,

has fashioned a visual, "flowing" language of pain and feeling of remarkable intensity and splendor.

It is worth saying that all of Bergman's great films seek to chart the astonishing flow of feeling.

Wild Strawberries

(1957) is arguably Bergman's most lyrical and haunting evocation of a life from every

angle—public record, memory, dream, hallucination—so as to illuminate the despotic affective material that has been repressed and demands to be acknowledged. Isak Borg, the doctor/protagonist of the film, has succeeded in a long professional medical career of great eminence, but the pot boils over nonetheless, and a kind of sentient lava fills the screen, in the guise of failed love, coldheartedness, fear of dying—as seen in the surrealist moments when the doctor encounters his own corpse in a coffin, when the doctor fails his medical exam, when the doctor watches his wife fornicating with a lover. Bergman constructs here, via the scenes of dream and hallucination, a gathering, withering indictment that Isak Borg's seemingly full life has been utterly hollow, not unlike the expose that Munch performed on his preening burghers in

Evening on the Karljohan.

Persona

(1965) finds still other ways to graph the libidinal currents that bind us in what we call pain or pleasure. In this dazzling, Picassolike opus, Bergman jettisons realist storytelling entirely, obliging us to recognize that the fluid, incestuous, double portrait of two women merging with each other opens up new frontiers. Bergman's theme here is the cannibalizing of one person by another, the fusion of selves, and he wants these psychological notions to become startlingly visible. Film can do just that, can show one image consuming another, can fuse its figures together, can offer scenes where the spectator cannot determine if these events are happening or just fantasized.

In film after film, Bergman does homage to the seemingly unpho-tographable world of feeling.

Autumn Sonata

(1978) cargoes the full temporal span of a hurting family into its plot of (concert pianist) mother visiting (stayed at home) daughter, so much so that we may feel that the poor mother (played unforgettably by Ingrid Bergman in her sole Bergman role) is virtually smothered, buried alive in all this mias-mic material, so many open sores that seem to live forever, invested with a quasi-radioactive virulence. Proust once said that time requires human bodies to write on, and I believe that Bergman's view is comparable, with a slight shift: feeling requires human bodies to write on, and

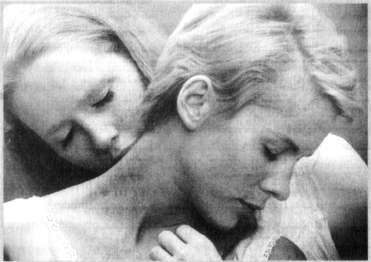

The vampirish embrace between Elisabet and Alma.

Persona

(1965).

it sovereignly does so over time, with the corollary that this system does not know "erasing." Bergman is notorious for the sheer length of some of his films—

Scenes from a Marriage

(1973) is about three hours in its short version,

Fanny and Alexander

(1983) is all of five hours in its original format—but this seems brief, given how much temporality is packed into these stories, stories that are epic as well as intimate.

Scenes from a Marriage

is a longitudinal study of marriage and divorce covering the good years, the beginning, middle, and end of the split, and then the aftermath. And that is exactly why it hits the target: marriage and even divorce are longitudinal realities, and their measure cannot be taken in snapshots. They are longitudinal because they embody a scream that goes through the house, an affective current that cannot be turned off when divorce (or even death) comes. Divorce leaves emotional scars, the muck that refuses to go away even though both partners are now "free." With a little license I'd like to apply to divorce what they now say about jet lag: you will experience a full day of out-of-

syncness for each hour of time zone you have crossed; which means that those years of marriage (and all the affective materials of which they are made) will mathematically require their due, get their boomerang-like revenge at divorce, entailing an equal (if not longer) number of years to reestablish your equilibrium, to shut out and to still that noise going through the house.

We must turn to Bergman's great

summa

of 1983,

Fanny and Alexander,

for his most evolved account of the pathways of feeling, of a visual geography that would at last chart the forces that link humans together. In

Fanny and Alexander,

all the pieces fall into place: at stake is no less than the whereabouts of spirit, spirit now understood as a kind of power that many institutions may lay claim to, but whose workings film might depict. This film has a strangely Foucauldian dimension to it, as if the old filmmaker were out to reveal how power works in his culture, and thus wanted to stage a kind of discursive and institutional warfare.

In this final film, the Church, with its repressive order and tyrannical claims (issues Bergman, whose father was a minister, had altogether too much firsthand knowledge of) appears as the archenemy, an enemy that is incarnate in the form of the father. Edvard the bishop emerges as Bergman's death-dealing Lutheran father, indeed, a version of Swedish patriarchy itself. Against him are arrayed the counterforces that matter: imagination and fantasy, as located in the child Alexander, Bergman's portrait of the artist as young man; and then, the power of art forms themselves: masks, mummies, plays, stories.

Fanny and Alexander,

while not preoccupied with illness or death as such, may still be the premier manifestation of this book's central thesis: art as rival to science, art as revelation of the way the universe actually works, art as graph of neural and emotional pathways (a higher EKG or EEG if you will, but in collective form), finally art as staggering human resource that helps us to a new picture of our situation. A mighty intensification is at hand, a gathering virulence, as Bergman opens wider and deeper his exploration of the manifold forces that bathe, inform, and co-