Armageddon (4 page)

While Roosevelt’s life reflected the highest ideals, he was a much less sentimental and more ruthless man than Churchill. Roosevelt possessed, claims his most recent biographer, “a more perceptive and less romantic view of the world than Churchill.” This proposition is justified insofar as Roosevelt recognized that the days of empires were done, while Churchill’s heart refused to accept the signals of his brain that it was so. Yet any claim of Roosevelt’s superior wisdom becomes hard to sustain convincingly in the light of the president’s failure to perceive, as Churchill perceived, the depth of evil which Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union represented. It may be true that the Western allies lacked the military power to prevent the Soviet rape of eastern Europe, but posterity is entitled to wish that Roosevelt had allowed himself to appear less indifferent to it.

The British considered that neither the president nor the U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, for all his greatness as lead manager of America’s war effort, exercised the mastery of strategy that was needed to finish the war quickly. “As [Roosevelt’s] grip slackened during the last year of his life,” argues one of the best historians of Anglo-American relations at this period, “. . . the President became in some ways a liability in terms of the effective conduct of United States and Allied business . . . his refusal to face the facts concerning his own state of health . . . suggest, not so much heroism, as is usually argued, but irresponsibility and an undue belief in his own indispensability, if not a love of power.” Even if this verdict is too harsh and ignores the likelihood that an elected replacement president in January 1945 would have been less impressive than Harry S. Truman, it is hard to dispute the assertion that Roosevelt’s judgement was flawed, his grasp upon events visibly slipping, from his 1944 re-election campaign until his death in April the following year.

Yet American vision about the most important strategic decision of the western war, the assault on the continent, had proved superior to that of the British. As late as the winter of 1943–44, Churchill continued to fight a rearguard action for his cherished Mediterranean strategy. He pursued the chimera of penetrating Germany through Italy and Yugoslavia. He remained instinctively anxious to defer an invasion of north-west Europe, which he feared could become a bloodbath reminiscent of the First World War. Painful experience of the limitations of Allied forces against those of the Wehrmacht, the greatest fighting machine the world had ever seen, dogged his consciousness. The prime minister always acknowledged that a confrontation in France must come sooner or later. But he remained uncharacteristically dilatory about its timing. General*

2

Sir John Kennedy, Britain’s Director of Military Operations, wrote after the war that he doubted whether the invasion of Normandy would have taken place before 1945 but for the insistence of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff: “American opinion on the landing in France in 1944 was, without a shadow of doubt, ‘harder’ than ours.” Franklin Roosevelt could claim personal credit for insisting that D-Day should take place when it did. Marshall, likewise, declared with some justice that one of his own principal wartime achievements was to resist Churchill’s follies.

In the summer of 1944, American confidence in Overlord was triumphantly vindicated on the battlefield. After ten weeks of bitter fighting in Normandy, German forces collapsed in rout. The broken remnants of Hitler’s forces staggered away eastwards, leaving almost all their tanks and guns wrecked upon the battlefield. The Allies had expected to fight river by river and field by field across France. Instead, Paris fell without a fight. In the early days of September, British columns streamed into jubilant Brussels, where they received a far warmer welcome than they had encountered from the French, among whom political and psychological wounds ran deep. “One got the impression that the Belgians felt they had done their bit by eating their way through the war,” said Captain Lord Carrington of the Guards Armoured Division, one of many Allied soldiers astonished by the plenty he found in Belgium, after years of privation at home in Britain. Courtney Hodges’s U.S. First Army approached the frontiers of Germany. The vanguard of George Patton’s U.S. Third Army reached the upper Moselle. Huge expanses of territory lay undefended by the Nazis. A few feeble divisions, supported by mere companies of tanks against the Anglo-American armoured legions, manned the enemy’s line. For a few halcyon days, Allied exhilaration and optimism were unbounded.

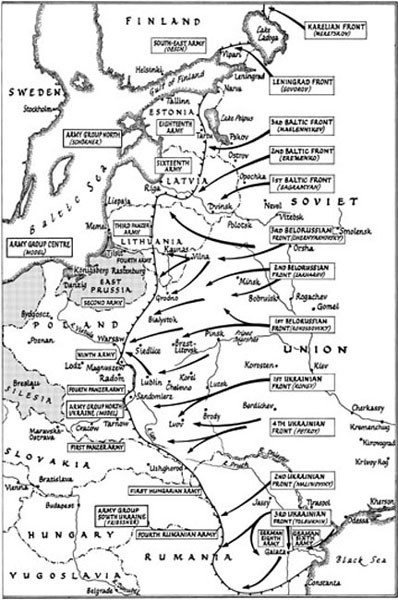

Meanwhile in the east, the Soviet Operation Bagration boasted triumphs to match those of the Americans and British. Indeed, the Russians’ achievement was much greater, since they faced three German divisions for each one deployed in France. Between 4 July and 29 August, the Red Army advanced more than 300 miles westwards from the start line of its northern summer offensive. The fervour of the Russians’ loathing for their enemy was intensified by the desert they found in Belorussia as the Germans retreated—crops ploughed into the ground, all livestock gone, a million houses burned, most of the population dead or deported for slave labour. Private Vitold Kubashevsky of 3rd Belorussian Front had already lived through two years of war, but recoiled in horror from what he now saw in Belorussia. Once he and his platoon noticed a stench emerging from a shed beside a church, and entered to find it stacked with the rotting corpses of local peasants. When correspondents reported on a Nazi death camp found at Maidenek in Poland, where the ashes of 200,000 people were still piled in the crematorium, some Western media—including the BBC—refused to publish their dispatches, suspecting a Soviet propaganda ploy. The

New York Herald Tribune

said: “Maybe we should wait for further corroboration of the horror story . . . Even on top of all we have been taught of the maniacal Nazi ruthlessness, this example sounds inconceivable . . .”

By September, the Red Army had recovered all but a small fragment of the Soviet territories lost since 1941. Stalin’s people, who had achieved their decisive victory over Germany at Kursk in July 1943, now stood at the borders of East Prussia, and on the Vistula within a few miles of Warsaw. The Germans clung to a mere foothold in Lithuania. Further south, the Russians had driven deep into Rumania, and held a line close to the capital, Bucharest. Only in the Carpathian Mountains did the Germans retain a narrow strip of Russian soil. German casualties were horrendous. Fifty-seven thousand captives from the Fourth Army were marched through the streets of Moscow on 17 July. Muscovite children jeered and threw stones. A watching six-year-old was so conditioned by propaganda images of the enemy that she noted her own astonishment on seeing that these Germans possessed human faces. She had expected to see the features of wild beasts. Most Russian adults looked on in grim silence. Yet a Western correspondent watching the shuffling parade of Germans was surprised to hear an old Russian woman mutter: “Just like our poor boys . . . driven into the war.” Between July and September, Hitler’s forces lost 215,000 men killed and 627,000 missing or captured in the east. One hundred and six divisions were shattered. Total German losses on the Eastern Front that summer—more than two million men killed, wounded, captured and missing—dwarfed those of Stalingrad. It was little wonder that Stalin and his marshals were dismissive of Anglo-American successes in France. A recent American study has described Bagration as “the most impressive ground operation of the war.” Yet if its gains were awesome, so was its human price. Russia’s summer triumphs cost the Red Army 243,508 men killed and 811,603 wounded.

In the second week of August, Marshal Georgi Zhukov—who had brilliantly orchestrated the summer operations of the two Belorussian Fronts—together with Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, his subordinate at 1st Belorussian Front, considered with Stalin the possibilities of an early thrust west across Poland, on an axis which would lead finally to Berlin. This was rejected, chiefly because Rokossovsky’s forces were exhausted by their long advance, and also because Stalin perceived opportunities elsewhere. Russia’s warlord committed his forces, first, to new operations on the Baltic Front, where some thirty German divisions held out in coastal enclaves, some of which they retained until May 1945; and, second, to a series of major offensives in the Balkans, where several countries lay ripe for Moscow’s taking.

Militarily, the Balkan campaign was rational but not essential. Politically, however, from Stalin’s viewpoint the temptation was irresistible. On 20 August, the Red Army launched a million men into Rumania, whose people were known to be ready to abandon Hitler’s cause. Allied bomber attacks were destroying the country’s oil industry. For many months, the Rumanian government had been exploring the possibilities of a deal with Moscow to change sides. Now, the Soviets advanced twenty-five miles on their first day in sectors unconvincingly defended by Bucharest’s forces. On 23 August, after a coup in the capital, Rumania announced its defection to the Allies. German intelligence, always the weakest arm of Hitler’s war effort, was taken wholly by surprise. Rumania would now provide the Red Army’s path to the Danube delta, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Some 70,000 German troops staged a fierce, brilliant breakout from Soviet encirclement, but many more found themselves cut off. The Red Army entered Bucharest on 31 August, having covered 250 miles in twelve days. The Rumanian Army had fought alongside the Germans, albeit ineffectually, throughout Hitler’s campaigns in Russia. Now, when a Rumanian delegation arrived in Moscow and was shown into the office of Stalin’s foreign minister, Molotov demanded contemptuously: “What were you looking for in Stalingrad?”

In Bucharest, the Rumanian Jewish writer Iosif Hechter described in his diary a mood of:

bewilderment, fear, doubt. Russian soldiers who rape women . . . Soldiers who stop cars in the street, order the driver and passengers out, then get behind the wheel and disappear. This afternoon three of them burst into Zaharia’s, rummaged through the strongbox, and made off with some watches . . . I can’t treat these incidents and accidents as too tragic. They strike me as normal—even just. It is not right that Rumania should get off too lightly. This opulent, carefree, frivolous Bucharest is a provocation for an army coming from a country laid waste.

When Hechter and his kind, delivered from the spectre of the death camps, clapped wildly as Soviet columns marched through the streets, other Rumanians “looked askance at the ‘applauding yids’.” Hechter gazed upon the weary, filthy, often ragged Red soldiers and reflected: “

Ils ne payent pas d’apparence

”—‘They don’t look much’—but they are conquering the world.”

Though the Soviets’ pace slowed as difficulties of supply and maintenance overtook their armies, they maintained their push throughout September. The battle for Rumania cost the Germans some 230,000 men, and the Soviet Union 46,783 dead and 171,426 wounded, along with 2,200 tanks and 528 aircraft. To maintain a perspective between east and west, we should note that one of the least bloody Soviet operations of 1944–45 thus incurred greater casualties than those of the British and Canadians in the entire campaign for north-west Europe. Bulgaria, however, fell without a shot being fired. As soon as Russian troops crossed its border on 8 September, they were greeted by their supposed Bulgarian adversaries assembled in parade order with red banners unfurled and bands playing.

Hardly a single one of the Soviet soldiers now pouring into eastern Europe had ever before set foot outside his own country. They were fascinated, and sometimes repelled, by a host of novelties. “Russians had a stereotype of Poland as a bourgeois capitalist state hostile to the Soviet Union,” writes a Russian historian. “I can’t say we liked Poland much,” wrote a Russian soldier. “We saw nothing noble there. Everything was bourgeois and commonplace. They looked at us in a very unfriendly way. They just wanted to rip off their liberators.” Rus-sian soldiers were ordered to respect Polish property, yet few took heed. When a man was reprimanded for stealing a sheep, his comrades protested. “Come on, we said,” one of them remembered, “what’s a sheep? This man has been fighting since Stalingrad.”

Lieutenant Valentin Krulik could not understand why Rumanian peasant houses allowed cooking smoke to seep out through their front doors, until he learned that the state imposed a chimney tax. After the desperate poverty of the Rumanian countryside, he and his men were bewildered to find the capital, Bucharest, ablaze with lights, its shops open and full of goods. As Major Dmitry Kalafati led an artillery battery through the first Bulgarian villages in his Willys jeep, their vehicles were bombarded with water melons. The first Bulgarian troops they met said simply: “We’re not going to fight you Russians.” Kalafati drove unimpeded for miles across Bulgaria and into Yugoslavia in his cherished jeep with the commander of 3rd Ukrainian Front. The Russians liked Yugoslavia, but some found the Yugoslav people, and especially Tito’s communist partisans, conceited and condescending: “They seemed to look down on us.” Lieutenant Vladimir Gormin, one of the Russian gunners supporting the Yugoslavs, admired the partisans’ spirit, but was doubtful about the tactical merits of their practice of advancing into action behind an accordionist singing nationalist songs. Yulia Pozdnyakova’s signals unit was billeted for a time in the immense castle of a Polish count. Among the flowerbeds were stone reliefs of Poles who had fought with Napoleon’s army in Russia in 1812. The young Russian girl felt very angry: “I was indignant that anybody could have lived like this count, waited upon hand and foot. I had never seen anything like it in Russia—the huge baths, the marble statues of naked women. It seemed all wrong.”