Armageddon (29 page)

A

T THE BEGINNING

of November 1944, the Soviets and the Western allies stood almost equidistant from Berlin. Stalin, passionately determined to ensure that the Soviet Union enjoyed its triumph in Hitler’s capital, still harboured some thoughts of launching an early thrust across the Vistula. Zhukov dissuaded him. Soviet offensive operations in Poland were halted, to prepare for the next phase of the great assault on Germany, to be launched at some date between 15 and 20 January 1945.

Stalin’s Stavka, the high command directing Russia’s war, considered three alternative plans. There was a southern axis, through Budapest and Vienna. There was a northern route, through East Prussia, where Soviet forces already heavily outnumbered the Germans. Yet it always seemed inevitable that the Berlin assault would be staged from the centre, by 1st Belorussian Front through Poland. In October 1944, Rokossovsky was supplanted by Zhukov as 1st Belorussian’s commander, and shifted northwards to direct 2nd Belorussian Front against East Prussia. Russian generals vied for primacy at least as eagerly as their Western counterparts. Rokossovsky, a commander of proven ability and with a willingness to delegate unusual among his peers, was furious at being moved to a subordinate role for no better reason than that he was half Polish. Stalin had no intention of allowing any sort of Pole to take Berlin. A lingering taint of the prison cell also hung over the marshal, who had been imprisoned during the 1937 army purges. “I know very well what Beria is capable of,” Rokossovsky once observed bitterly to Zhukov. “I have been in his prisons.” Here was one of the greatest Soviet generals of the war, who had emerged from confinement without his fingernails amid the miasma of suspicion and persecution during the purges just seven years earlier.

On Zhukov’s left flank in Poland stood 1st Ukrainian Front, led by the swaggering, shaven-headed figure of forty-eight-year-old Marshal Ivan Konev. A former tsarist NCO, he was a man of little education, and found it difficult to express himself on paper. It was his fate always to be overshadowed by Zhukov, yet he had proved himself an almost equally effective commander, and enjoyed the additional merit in Stalin’s eyes of being less celebrated by the Red Army. Zhukov had saved Konev from obscurity, or something worse, and secured his rehabilitation after he was summarily dismissed from his command by Stalin in February 1943, as so many able officers were likewise dismissed. Konev is sometimes described as “ruthless.” This adjective seems superfluous in speaking of any Soviet commander. None could hold his rank or perform the tasks demanded of the Red Army without possessing a contempt for life unusual even in the ranks of the Waffen SS. Konev had come within a whisker of execution by Stalin, during the bloody torrent of recrimination that accompanied the 1941 battles for Moscow. There is no biographical evidence to suggest that Stalin’s marshals possessed either cultural refinement or humanitarian scruple, that any was, in truth, much more than a militarily gifted brute.

Zhukov forcefully argued to Stalin, who needed little persuasion, that the principal drive into Germany must be made on Russia’s central front, with its main weight deployed south of Warsaw. This view prevailed. It was obvious, however, that pressure must be maintained in East Prussia, Hungary and Yugoslavia, to ensure that the Germans could not shift forces to Poland from the Baltic area and south-east Europe. The broad principles of future operations were established. Zhukov would strike the main blow south of Warsaw, while Konev on his left sought to envelop the vast industrial areas of Silesia, rather than attack head-on against strong defences. Stalin was anxious to capture Silesia’s mines and factories intact, and emphasized his wishes to Konev. In the north, Chernyakhovsky and Rokossovsky would address East Prussia.

The Germans were defending the west with seventy-four divisions and 1,600 tanks, against an Allied army of eighty-seven vastly stronger divisions and over 6,000 tanks. In the east, the Germans deployed some two million men, 4,000 tanks and 2,000 aircraft. Against these, by January 1945 the Red Army would be able to commit six million troops. Its order of battle boasted 500 rifle divisions—each half the size of its Western counterpart—13,000 tanks and self-propelled guns, 100,000 guns and heavy mortars, 15,000 aircraft. In the past, Russian armies had often attacked in the frozen winter months, when the ground and even the rivers could carry tanks. Traditionally, it was in the spring thaws that the Eastern Front became stagnant. But on the Vistula in November the logistical difficulties were immense. Eastern Europe lacked the road and rail network of the west. The Germans had demolished every possible communications link during their summer retreat. Though the Red Army was far better supplied with transport than it had been two or three years earlier, it possessed nothing like the resources of the Americans and British. Many of the new replacements reaching the Russian formations were ill trained. For the best part of three waterlogged and then snowbound months, therefore, while fierce fighting persisted to the north and south, the critical axis of the Eastern Front lay dormant, as Stalin’s armies began the build-up for their decisive blow in the battle for Germany.

CHAPTER FIVE

Winter Quarters

THE SCHELDT

A

FTER THE FAILURE

of Market Garden, Montgomery described its only legacy—the long, thin salient to Nijmegen—as “a dagger pointed at the heart of Germany.” This was a characteristic piece of braggadocio by 21st Army Group’s commander. Privately, he cannot have believed it. The point of that “dagger” drove nowhere until the spring of 1945. To hold the eastern “blade,” a sixty-mile front, he was obliged to retain for weeks the services of the two U.S. airborne divisions which had seized the corridor in September 1944. In October the most urgent objective for Montgomery’s forces lay in the opposite direction from Germany: the Antwerp approaches. Tedder wrote: “I was never able to convince myself that at any stage until we held Antwerp, Montgomery really believed that we could march a sizeable army to Berlin with our existing resources of supply and maintenance.”

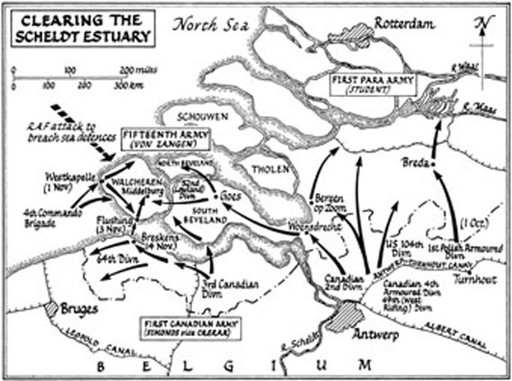

First Canadian Army was committed to the unglamorous yet vital task of clearing the Scheldt, and above all the defences of Walcheren Island, to open the shipping path to the port. Operations began on 3 October, with a devastating air attack against the Westkapelle Dyke by 247 Lancasters of Bomber Command. When the RAF aircraft turned for home, the great earth wall that had held back the sea from Walcheren for 400 years was breached. Within a few days, large parts of the island were under water, flooding some German positions, at the cost of 125 Dutch civilian lives. But during the first ten days of October the ground advance made slow progress. Throughout the campaign, the Canadian Army suffered even more acutely than the British from a shortage of men. Because many French-Canadians bitterly opposed participation in “England’s war,” Canada’s prime minister Mackenzie King decreed in 1940 that only volunteers would be sent overseas, and that even these men would fight only in Europe. As a consequence, by 1944 some 70,000 fit Canadian soldiers—the “zombies” as they were known—remained at home, doing nothing more useful than guarding prisoners of war. “We had five divisions, or the equivalent, of trained men sitting back there in Canada,” lamented a Canadian officer bitterly, “and that s.o.b. Mackenzie King just wouldn’t send them overseas.” At the very end of the war, when 15,000 non-volunteers were drafted for overseas services, more than three-quarters of them deserted before embarkation.

Meanwhile in the field, Canada’s fighting forces suffered constant manning difficulties. When the units which had trained for so long in England before D-Day were eroded by battle casualties, the quality and fighting power of the Canadian Army deteriorated, to the chagrin of those who commanded its units in battle. The Black Watch of Canada, for instance, had suffered heavily in Normandy, and by October possessed only some 379 men in its rifle companies, of whom 100 were recent replacements. Many of these proved wholly untrained, to the point of being unfamiliar with infantry small arms. When they met German paratroops in an attack on 13 October, they were heavily mauled, losing 183 casualties including fifty-six killed. That night, the survivors were given a hot meal and a movie show. When officers learned that the scheduled entertainment was entitled

We Die at Dawn,

a less provocative alternative was substituted.

On 16 October, the commander of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, Lieutenant-Colonel Denis Whitaker, was consolidating his battalion’s positions after a successful assault when the German 6th Parachute Division counter-attacked. Whitaker was appalled to see his A Company commander shamelessly about-turn and disappear towards the rear. “Unfortunately,” wrote the colonel later, “when men see their own leaders turn away from battle, it becomes a very natural choice that they shall follow, and that is what happened on Woesdrecht Hill. I . . . had to watch this horrible sight, those wretched men running panic-stricken down the hill towards us. I pulled out my revolver and stopped some of them at gunpoint.” Whitaker’s battalion suffered 167 casualties, including twenty-one killed. One of his other company commanders checked the German assault by calling down artillery fire on his own positions.

On 31 October, the CO of the Black Watch of Canada, Lieutenant-Colonel Bruce Ritchie, wrote a note for his battalion’s war diary: “ ‘Battle morale’ is definitely not good, due to the fact that inadequately trained men are, of necessity, being sent into action ignorant of any idea of their own strength, and, after their first mortaring, overwhelmingly convinced of the enemy’s. This feeling is no doubt increased by their ignorance of fieldcraft in its most elementary form.” Individually, many Canadians made fine and brave contributions to the war. Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds was among the outstanding corps commanders in north-west Europe. Some Canadian officers who volunteered for service with British units showed themselves exceptional soldiers. But collectively, the Canadian Army was a weak and flawed instrument because of the chronic manning problems imposed by its nation’s politics. Canada’s soldiers paid the price of their prime minister’s pusillanimity on the flooded battlefields of Holland in the winter of 1944.

Eisenhower told Montgomery, undoubtedly rightly, that he was unconvinced 21st Army Group was giving sufficient priority to Antwerp: “I believe the operations designed to clear up the entrance require your personal attention.” The field-marshal grudgingly reinforced the Canadians with four British divisions, which pushed north towards the Waal. A painful struggle followed. Some 10,000 Germans in the so-called Breskens Pocket inflicted on the Canadian 3rd Division some of the most miserable fighting of its war, amid the October rains and floods. The Wehrmacht’s 64th Division, core of the Breskens defence, was one of the most effective formations under Model’s command. The Leopold Canal, which had caused such grief during the first Canadian crossing attempt in September, required a major assault operation three weeks later. A soldier of the Toronto Scottish recorded in the battalion’s war diary for 9 October: “Living conditions at the front are not cosy. Water and soil make mud. Mud sticks to everything. Rifles and brens operate sluggishly. Ammunition becomes wet. Slit trenches allow one to get below the ground level, but also contain several inches of thick water. Matches and cigarettes are wet and unusable.” A Canadian officer, Major Oliver Corbett of the North Shores, said: “The whole Scheldt battle was company attacks, day after day, sometimes two or three attacks in 24 hours . . . We were soaked all the time. Along the dyke was the only place a soldier could dig in.”

Among the British formations further south, Private Kenneth Pollitt advanced into the old fortress town of ’s-Hertogenbosch with 7th Royal Welsh Fusiliers on 26 October. A young Dutchman wearing the Orange armband of the Resistance dashed to meet Pollitt’s platoon, and volunteered to show the way through the streets, because he desperately wanted to play some part in the liberation of his hometown. They reached the town hall, where even amid continued fighting local people were offering celebratory glasses of wine to every passing British soldier. They moved on towards the south bank of the canal, failing to notice a German tank tucked in beside a building on the far side, 150 yards away. Its gun fired. Most of Pollitt’s section collapsed dead or wounded. His corporal was hit in the stomach, face and legs. The Dutch boy was dead. “That one shell cost our platoon more casualties than we had suffered since Normandy.” Pollitt dashed into a nearby monastery, and tried to find a window from which he might get a shot with his PIAT. The Germans had disappeared. Next morning, he heard cheering, and ran out on a house balcony to see men of the East Lancashires making a dash across a canal bridge. Yet, even as they watched, a German sniper dropped one of the spectators stone dead. Carelessness on the battlefield was often cruelly punished. Shelling started, from both sides. Pollitt watched curiously as a dispatch rider, obviously very drunk, stood in full view in the street and blazed wildly in the direction of the German positions with a tommy-gun. He was fortunate enough to survive, “the only man I saw drunk in action in the whole campaign.” It took the British two days to secure ’s-Hertogenbosch and its network of canals, just one among a hundred such bitter and destructive little actions.