Armageddon (15 page)

A bitter sense of anticlimax followed Market Garden. The British would be leading no triumphant advance into Germany through Holland and the Ruhr. Second Army Intelligence recorded ruefully on 29 September: “The enemy has gained a respite, of which he has taken fuller advantage than it was supposed he might manage.” De Guingand, Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, always believed that, even if XXX Corps had broken through to Arnhem, “the Germans would have produced an answer to the single thrust into Westphalia favoured by Monty.” The dash for Arnhem was the last occasion of the war when Eisenhower unequivocally accepted a strategic proposal advanced by Montgomery. There is little doubt that the resources employed upon Market Garden should instead have been devoted to the far less glamorous task of clearing the approaches to Antwerp, which thereafter occupied a large part of Montgomery’s forces for two months. The true cost of the Rhine operation was not failure to secure the bridge, but the diversion of the army and its supplies at a vital moment when they should have been otherwise employed.

Arnhem was a British idea. Operational responsibility for its failure must rest chiefly with 21st Army Group’s commander. Almost all his American peers revealed private satisfaction at the spectacle of Montgomery suffering such a rebuff. General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, senior USAAF officer in Europe, drafted a scathing letter to a friend in which he said that “any deficiency in the operation was probably more the fault of the famous British General Montgomery than any other cause.” Eisenhower cannot escape all blame, however. September saw the end of the first phase of the north-west Europe campaign. Thereafter, unusual opportunities presented themselves, if only the Allies had shown themselves able to exploit these more effectively, and if their forces had been led by a commander who displayed the grip to which Montgomery rightly attached such importance. Instead, however, Eisenhower’s new headquarters at Granville in Brittany was, at a crucial period in early and mid-September, disastrously handicapped by poor communications. Signals sometimes took twenty-four hours or longer to reach the Supreme Commander’s desk. His staff was shaking down in its new responsibilities. He himself was labouring under grave misapprehensions—albeit shared by his subordinates—about the terminal weakness of the enemy.

Yet, by his own choice, Eisenhower had assumed command of the Allied ground forces and was thus the man in charge. We shall explore below the possibilities available to the American armies in September. That month, there was a real chance of breaking into Germany in 1944—by opening Antwerp, and by breaking von Rundstedt’s line on Bradley’s front, rather than by adopting the ill-conceived British Arnhem plan. While the Supreme Commander was still gathering the reins of authority, as ever the Germans were labouring furiously. By October, the window of opportunity on the Western Front had slammed shut. It is ironic that Dwight Eisenhower’s first serious error as ground commander was to allow Montgomery, the man who wanted his job, to have his own way over Market Garden. The Supreme Commander could have made a notable contribution to ending the war in 1944 by asserting other priorities, and preventing Montgomery’s Arnhem adventure from taking place at all.

CHAPTER THREE

The Frontiers of Germany

FADING DREAMS

T

HERE WAS NEVER

a specific moment in the late autumn of 1944 at which the Western allies resigned themselves to continuing the war into 1945. Arnhem loomed larger in the consciousness of the British than in that of a GI in a foxhole in Alsace-Lorraine. Rather, as each local offensive faltered, as German resistance stiffened, and above all as incessant rain and the movement of the armies ploughed the battlefield between Switzerland and the sea into a quagmire, commanders progressively diminished their expectations and moderated their ambitions. Each small disappointment or failure fed the next.

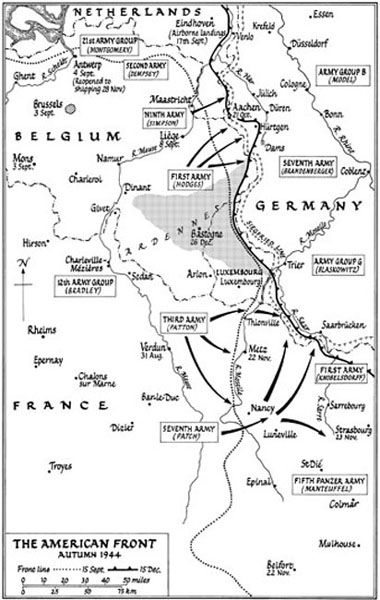

In the historiography of the Second World War, millions of words have been expended upon the British defeat at Arnhem, where prospects of success were always slight. Montgomery’s failure to secure the approaches to Antwerp has been discussed. Yet the best chances of breaking through into Germany in 1944 lay many miles further south, around Aachen and in the hills and forests of the Ardennes. During their summer planning sessions, Eisenhower’s staff eliminated the Ardennes from the list of prospective Allied routes into Germany. In considering options, they talked only of the northern and southern sectors of the front, with the Ardennes as a hinterland in between, unconsidered as a site for offensive operations. This was probably a mistake. Once already in the war, in 1940, the Germans had demonstrated what could be done by determined men among the Ardennes passes, and of course they would so again in Decem-ber 1944. It became impossible to send large forces through the Ardennes once the Germans stiffened their line in October, but in September something important might have been achieved there. At that stage, however, the Allied planners believed that other and easier avenues lay open.

The principal American command in the west was held by the fifty-one-year-old Missourian Omar Bradley of 12th Army Group. This was already larger than Montgomery’s 21st, and was destined to keep growing fast through the months that followed. Bradley was responsible for two armies, which would eventually become four, the greatest American force in history to be led by a single officer. It was a myth created by the correspondent Ernie Pyle that Bradley was beloved of his men as the “soldiers’ general.” Patton and Montgomery were the only two senior commanders familiar to their own men, because both took great pains to see that it was so. Bradley had risen to his role not because of any conspicuous feat of generalship, but because he inspired confidence among his peers and possessed a well-deserved reputation for efficiency and grasp of logistics—a science which Patton, for one, neglected. During their time together in the Mediterranean, Eisenhower had grown implicitly to trust and respect Bradley, who had commanded first a corps and then an army there: “the best rounded combat leader I have yet met in our service,” Ike wrote to Marshall. “While he probably lacks some of the extraordinary and ruthless driving power that Patton can exercise at critical moments, he still has . . . force and determination . . . a jewel to have around.” Amid the stresses to which Eisenhower was subjected by Montgomery and in some degree by Patton, it was a relief for him to turn instead to the plainspoken, reliable 12th Army Group commander, a keen bridge-player and expert rifle shot since his rural childhood.

In recent years, Bradley has incurred harsh censure from some critics, notably the American historian Carlo d’Este, who dismisses him as a plodder. In north-west Europe, to his own detriment the Missourian allowed exasperation with Montgomery to become an obsession. For all his customary steadiness, Bradley was prone to outbursts of savage temper. He showed himself far more ruthless than Montgomery in sacking corps and divisional commanders, while he was no more successful than the British commander in persuading his armies to hurry on the battlefield. In one important respect, however, Ernie Pyle’s judgement on Bradley was correct: 12th Army Group’s commander wanted to do the business of defeating the Germans with the maximum application of American firepower and industrial might, and the least possible expenditure of American lives. He had not come to Europe to prove himself a Rommel or von Manstein. He intended to take every possible American under his command home with him again. For this, indeed, he deserved the gratitude of his soldiers.

O

N

13

S

EPTEMBER

, Bradley’s forces—men of Hodges’s First Army—were close to Aachen, and barely sixty miles from Cologne, on the Rhine. Yet it would be almost six months before they took the latter city and closed up to the greatest of Germany’s rivers, a mere hour’s road drive from their autumn front line. In August and early September, Patton’s Third Army had pushed some 500 miles across France in twenty-six days. America’s other armies had likewise advanced far and fast. From September until the early spring of 1945, however, most of the fighting along the entire front would take place within a belt of Dutch, Belgian, German and French territory ten to twenty miles deep. Before D-Day, Churchill feared that the Allied armies would become locked in a long battle of attrition in Normandy. In reality, they were able to break out of their D-Day beachhead and secure a critical victory in little more than two months. Yet in Holland, in the western hills of Germany and in the fields of Alsace-Lorraine, the liberators became stalemated for almost half a year, making small advances at painful cost. Once momentum had been lost, it was not regained until the Germans were ground down in battles etched painfully into the legend of the U.S. Army. American failures were less spectacular than those of the British in Holland, but they were at least as serious in delaying the end of the war.

Part of the German—and sometimes Russian—genius for war was a readiness to seize opportunities with both hands, swiftly to exploit weakness before the enemy could reinforce a threatened spot. At no time in the north-west Europe campaign before the Ruhr Pocket in April 1945 did Anglo-American forces achieve the kind of comprehensive envelopment of enemy forces which was commonplace on both sides of the Eastern Front. Even the undoubted disaster inflicted upon the Wehrmacht at the Falaise Gap in August 1944 was incomplete, and allowed the escape of just sufficient men to provide skeletons upon which broken formations could be clothed with the flesh of new men and equipment.

“The Allied drive lost its impetus with reaching of the Siegfried line in the north and the Moselle river in the south,” recorded the U.S. Army’s official post-war report on “Strategy in North-West Europe.” “The prepared enemy positions, the extent of the area covered by the Allied troops over a short space of time, and the need for additional supplies at forward points to sustain the drive, made it apparent that no further large-scale offensive could be launched until additional forces could be concentrated and the logistical situation improved . . . A period of relative inactivity was essential.”

This comfortable official declaration of the inevitability of what took place in the autumn of 1944—or rather did not take place—masks complex issues and possibilities. All the paper arguments about the Allies’ logistical difficulties in early September are valid. But a greater field commander than Eisenhower, together with a more vigorous spirit of enterprise than that which prevailed in his armies, might have overcome the difficulties and found means to drive forward into Germany while the Wehrmacht was still reeling. No setback could alter the inevitable outcome of the war, but the Germans used every day of delay to greater advantage than did the Allies. It was unrealistic for Eisenhower to suppose in September that his armies could head straight for Berlin. The sheer mass of German forces still available to defend the Reich militated against a successful one-stop dash for Hitler’s capital. But the Allies could and should have got to the Rhine, beyond which there were no further significant terrain features to assist the defence, before winter imposed its deadly grip upon military movement.

Patton’s Third Army ran out of fuel in eastern France, well before reaching Hitler’s West Wall, the Siegfried Line. Once his tanks were refuelled, they sped onwards to reach the ancient fortress city of Metz, on the Moselle, on 8 September. Patton expected an easy victory here. The planners were oblivious of the strength of the great chain of sunken forts created in a belt around Metz over a period of 200 years. They received a brutal shock. The Germans had garrisoned the forts strongly, and were reinforcing fast. Not only could the Americans not seize them, but enemy shellfire from Metz rained down on Third Army’s bridgeheads thrown across the Moselle.

The U.S. 317th Infantry suffered much misery at the river, beginning on a warm, clear day, 5 September, when the regiment made its first attempt to cross. Rain over American airstrips precluded fighter-bomber support, and it was decided to attack without artillery preparation. The 1/317th jumped off at 0930, crossing a canal over a partly demolished footbridge. At 1000, the unit halted in the face of enemy machine-gun fire, soon afterwards followed by shelling. American counter-battery fire silenced the German artillery, and at 1030 B Company reached the river bank. Almost half an hour later, as the Americans launched their boats, five were destroyed by mortar fire. By 1500, C Company had withdrawn to its start line, while A and B had dug in along the nearby canal. That night, the 1/317th tried again. German concentrations of mortars and machine-gun fire destroyed most of the boats “and demoralized the troops,” according to the corps’ after-action report. Although the battalion had suffered few casualties, a regimental staff officer reported it “unfit for further immediate action.” The 2/317th was late leaving the start line for its own crossing. As it launched its boats in tense silence, a German voice shouted from the far bank: “

Halt! Machinen gewehr!

” German guns began to fire across the water on fixed lines, and the crossing was abandoned. The regiment’s third battalion got clear over the Moselle by 1500 on 5 September. But energetic German counter-attacks drove in its bridgehead. The Americans retired to the western shore.