Ardor (38 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Then the unprecedented gesture occurs. They do not sacrifice it, they do not deliver it up to the priests as a ritual fee, but “they release it.” In that instant the whole sacrificial edifice is in danger of collapsing. How can a domestic animal, destined for sacrifice or to be offered as a ritual fee to the priests, be released—to wander about once again like a forest animal? If this happens, it becomes an ordeal. Without human interference, the direction chosen by the released cow determines the fate of the sacrificer: “If, not being goaded by anyone, it goes eastward, let him know that this sacrificer has been successful, that he has conquered the world of happiness. If it goes northward, let him know that the sacrificer will become more glorious in this world. If it goes westward, let him know that he will be rich in servants and crops. If it goes southward, let him know that the sacrificer will soon depart from this world. These are the ways of finding out.” The same happened to St. Ignatius of Loyola and his mule, whom Ignatius, still a layman and a warrior, allowed to choose between two roads: one of which would certainly lead to murder; the other of which would ultimately mean sainthood. If the S

ā

hasr

ī

wanders southward, the sacrificer knows his death is imminent. The immense effort of the sacrifice has been worth nothing. And so too have been the nine hundred and ninety-nine cows given as a ritual fee to the priests. And all because that one, single cow went southward. “These are the ways of finding out.”

* * *

However he was considered, Praj

ā

pati always appeared unique. Even when the gods were counted: “There are eight Vasus, eleven Rudras, twelve

Ā

dityas; and these two, Sky and Earth, are the thirty-second and thirty-third. And there are thirty-three gods and Praj

ā

pati is the thirty-fourth.” Praj

ā

pati’s supernumerary nature was his unfailing characteristic. Praj

ā

pati was always

extra

—and it is precisely to this that the ritualists connected the link between surplus and residue. They saw that they were the same question. And the question was Praj

ā

pati himself. Praj

ā

pati is

that which remains.

Praj

ā

pati is the superfluous part from which all that is necessary is born.

* * *

Surplus

and

residue

are ever-present. Especially in time. The day that marks the climax of the year is the

vi

ṣ

uvat

—and that is a

surplus

day. Without that day, the year would be divided into two equal parts, in which each rite could have its identical counterpart. But the

vi

ṣ

uvat

places this perfect symmetry at risk. The question is: “‘Does the

vi

ṣ

uvat

belong to the months that go before or those that follow?’ He must reply: ‘Both to those that go before and those that follow.’” Why? “Because the

vi

ṣ

uvat

is the torso of the year and the months are its limbs.” And a body cannot do without its torso. And then again: the year is a great eagle. The first six months are one wing and the other six the other wing. And the

vi

ṣ

uvat

is the body of the bird. That

surplus

day, the

vi

ṣ

uvat

, is therefore indispensable: only this interval can keep time together, can enable it to spread out two perfectly symmetrical wings, that extra day alone gives completeness to the year, where the rites each occur in correspondence with their counterpart, in the first and in the second half. Only in that way, with the last ceremony (the stairway that is climbed emerging from the ocean of the rite) do we reach the “world of heaven, the place of quietness, of plenty.”

Having reached the end of this crucial demonstration, since the proper conduct of the whole liturgy depends upon it, the ritualist allows himself a meditative

aside

, serious in tone, almost a confession by someone who has spent his whole life carefully, steadfastly, examining this subject: “These are indeed the forests and the ravines of the sacrifice, and hundreds and hundreds of days are needed to travel them by chariot; and if anyone ventures into them without knowledge, then hunger or thirst, marauders and wicked demons will assail them, in the same way that wicked demons would attack fools who wander in a wild forest; but if they who know do so, they pass from one task to the other, as from one river to the other and from one safe place to the other, and they reach bliss, the world of heaven.” Then suddenly, as if he had become carried away for a moment in contemplating his life and all his past experience—and this was against the rule—the ritualist patiently returns to a technical detail of the liturgy, to preparing answers to those who are always asking pointless and captious questions about this and that.

* * *

“That is full, this is full. / Full gushes forth from fullness. / Even after the full has been fully drawn upon, / this full remains full.”

We encounter the “stanza of plenitude” at the beginning of the penultimate

adhy

ā

ya

of the

B

ṛ

had

ā

ra

ṇ

yaka Upani

ṣ

ad.

Paul Mus wrote a masterly commentary on it. But, as the words of the stanza say, what it describes is boundless. And it might be placed at the very center of Vedic thought—even if the word

thought

may, in this case, seem reductive. The closest proximity to

full

,

p

ū

r

ṇ

a

, mentioned in the text is a passage in the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a

, which reads: “The gods certainly have a joyous Self; and this, true knowledge, belongs to the gods alone—and indeed whosoever knows this is not a man but one of the gods.” The real difference between gods and humans does not lie exclusively in the immortality that the gods have laboriously achieved—and which they want to keep only for themselves. It lies in a particular kind of knowledge, which corresponds to the joy gushing forth from the depths of Self. Ultimate knowledge is neither impassive nor immovable, but resembles the perpetual flow of plenitude in the world. The Vedic cult of knowledge is directed toward this image.

“When the yonder world overflows, all gods and all beings subsist on it, and truly the yonder world overflows for he who knows this.” All is possible—even the existence of the gods—only because “the yonder world” is superabundant. Its bursting forth into the other world, which is ours, offers that surplus without which there would be no life.

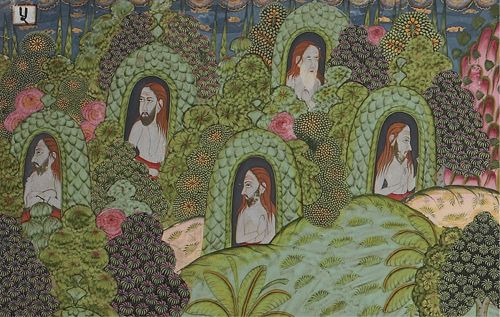

XIV

HERMITS IN THE FOREST

The

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

, the “renouncer,” in whose traits Louis Dumont had the farsightedness to recognize the archetypal

individual

in the Western sense, is a figure who does not appear in the earliest stratum of the Vedic texts. The system, at that time, is compact and leaves no such space. Having once entered the process of cosmic interaction on birth, there is no way out. But on reaching the Upani

ṣ

ads, which take ritualist reasoning to an extreme, the

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

makes his appearance—the first defector, not because he rejects the complex system of interaction on which ritual is based, but because he seeks to absorb it within himself, in the inaccessible space of the mind. So the

agnihotra

becomes the

pr

āṇā

gnihotra

, the first case of the complete internalization of an event, an invisible ceremony that takes place in an individual’s “breath,”

pr

āṇ

a.

There is no longer any fire, there is no longer any milk to pour on it, the words of the texts are no longer to be heard. But all this still exists: in silence, in the activity of the mind. And so the

inner man

makes his first appearance in history. He is the “individual-outside-the-world,” who has severed his links with society—and who will eventually prove to be enormously effective in his action

upon

society. Dumont recognizes in him the earliest figure of the

intellectual

, right up to his most recent awkward or lethal manifestations.

* * *

The

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

can quite properly be described as the inner man, since it is he who first internalized the sacrificial fires. Thanks to a subtle elaboration of correspondences, the factors that made up the liturgy of the Vedic sacrifice are moved into the body and into the mind of the

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

; and so he becomes the only being who need not keep fires burning, since he keeps them within himself. With the advent of the renouncer, sacrificial violence no longer leaves any visible traces. All is absorbed into this solitary, emaciated, wandering being, who would eventually become the very image of India. Not the man in his village or in his house. But the man of the forest—a place of secret learning, a place far removed from social constraints.

There is no mention of

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sins

in the

Ṛ

gveda.

They hardly dominate the scene in the Br

ā

hma

ṇ

as, which are filled instead with the figures of mighty and forbidding brahmins like Y

ā

jñavalkya, virtuous warriors well practiced in dangerous disputations on

brahman

, the king’s counselors and rivals. But, once again, it is in the liturgical literature—particularly the S

ū

tras—that we find the answer to a vital question that is rarely asked: how did the

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

first come into being?

The answer is disconcerting when we think of the mild image, alien to any form of violence, that has been passed down to us: the

sa

ṃ

ny

ā

sin

originated from the

puru

ṣ

amedha

, the human sacrifice. Here almost all scholars prefer to stay on the safe side and suggest that this ceremony must have been described in the Br

ā

hma

ṇ

as and in the S

ū

tras only

for completeness

, in that it corresponded to the formal layout of the sacrifices, but was never practiced—or else practiced in earliest times but then abandoned. This is all possible, but it cannot be confirmed or denied with any certainty. What remains is a series of texts. And these texts describe

puru

ṣ

amedha

in the same way as various other kinds of sacrifice. But this is not proof that certain deeds took place. And it is plausible to raise a doubt over

puru

ṣ

amedha

in much the same way as we may doubt that certain other rites were celebrated, given their interminable duration and complexity. Yet here, as always, it is wise to follow the texts. It is the

K

ā

ty

ā

yana

Ś

rauta S

ū

tra

, with its rugged concision, that reveals its points of connection. Above all: the

puru

ṣ

amedha

is modeled on the “horse sacrifice,”

a

ś

vamedha.

And so, whereas the rules governing the latter are set out in two hundred and fourteen aphorisms, those on the

puru

ṣ

amedha

require only eighteen, as if it were a secondary variation (which is in turn duplicated immediately after in the

sarvamedha

, the “sacrifice of everything”). But far more significant are the differences. Anyone wanting to celebrate an

a

ś

vamedha

has to be a king or have a “desire of the Whole”: it is the maximum expression of sovereignty. To celebrate a

puru

ṣ

amedha

it is enough to be a brahmin (or a

k

ṣ

atriya

) and “desire excellence.” This already points us in the direction of the individual who is defined by his desire alone. Another indication comes from the requirement that the brahmin sacrificer has to give, as a ritual fee for the sacrifice, “all his possessions.” What then will happen to him, stripped of all his belongings after having sacrificed a man? The answer comes in the penultimate aphorism: “at the end of the

traidh

ā

tav

ī

i

ṣṭ

i

[a certain kind of oblation, to be offered at the end of the sacrifice], the sacrificer assumes the two fires within himself, offers prayers to S

ū

rya, and, reciting an invocation [which is specified], goes off toward the forest without looking back, never to return again.” This is the moment where the figure of the renouncer emerges: when he takes his first step toward the forest, without looking back and knowing he will never return. In this instant, the brahmin cuts all links with his previous life. Never again will he have to celebrate the

agnihotra

at dawn and sunset, pouring milk on the fire, performing a hundred or so prescribed gestures, reciting formulas. Indeed, the renouncer no longer has to kindle and feed the sacrificial fires, since he will tend them within himself. Nor will he have to comply with countless obligations that make up his life as a brahmin. Now he will eat nothing but berries and roots when he finds them in the forest. His life will interfere only to a minimal extent with the course of nature. But what lies beneath all this? The celebration of a

puru

ṣ

amedha

, wanting a man to be killed in a sacrifice planned in order to establish the personal “excellence” of the sacrificer? We will never know whether this was ever carried out, even just once. Perhaps it was there only as a set of instructions, necessary for the formal completeness of the liturgical doctrine. But its significance still stands out in the text. And it is the supreme paradox of “nonviolence,”

ahi

ṃ

s

ā

.