Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (44 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Monty appeared at the press conference on 7 January wearing a new airborne maroon beret with double badge, having just been appointed colonel commandant of the Parachute Regiment. His chief of intelligence, the brilliant academic Brigadier Bill Williams, had read the draft of his speech and dreaded how it would be received, even though the text as it stood was relatively innocuous. The only provocative part was when he said:

‘The battle has been most interesting

– I think possibly one of the most interesting and tricky battles I have ever handled, with great issues at stake.’ The rest of the text was a tribute to the American soldier and a declaration of loyalty to Eisenhower, and a plea for Allied solidarity from the press.

But then, having reached the end of his prepared statement, Montgomery proceeded to speak off the cuff. He gave a brief lecture on his ‘military philosophy’. ‘If he [the enemy] puts in a hard bang I have to be ready for him. That is terrifically important in the battle fighting. I learned it in Africa. You learn all these things by hard experience. When

Rundstedt put in his hard blow and parted the American Army, it was automatic that the battle area must be untidy. Therefore the first thing I did when I was brought in and told to take over was to busy myself in getting the battle area tidy – getting it sorted out.’ Montgomery also greatly exaggerated the British contribution to the battle, almost making it sound as if the whole thing had been an Anglo-American operation.

In London the Cabinet Office commented later that

‘although this statement

, read in its entirety, was a handsome tribute to the American Army, its general tone and a certain smugness of delivery undoubtedly gave deep offence to many American officers at SHAEF and 12th Army Group’.

Many journalists present fumed or cringed, depending on their nationality, yet both the British and the American press concentrated on the positive aspects of what he had said. The next morning, however, a German radio station put out a fake broadcast on a BBC wavelength, with a commentary which deliberately set out to stir American anger, implying that Montgomery had sorted out a First US Army disaster.

‘The Battle of the Ardennes’

, it concluded, ‘can now be written off thanks to Field Marshal Montgomery.’ This fake broadcast was taken as genuine by American troops and the wire services. And for some time afterwards, even when it had been revealed that it was a Nazi propaganda trick, many aggrieved Americans still believed the British were just trying to bolster their role because their international standing was failing fast.

Even before the Nazi broadcast, Bradley was so angry that he rang Eisenhower to complain about Montgomery’s statement, and expressed his fear that the Ninth Army would be left under British command. He begged Eisenhower to

‘return it to me if it’s only for

twenty-four hours for the prestige of the American command’. He explained to Hansen that

‘I wanted it back for prestige reasons, because the British had made so much of it.’

Bradley still went on that day about Montgomery’s order to the 82nd Airborne to withdraw.

Without warning Eisenhower, Bradley called his own press conference on 9 January. He wanted to justify the weakness of the American forces on the Ardennes front on 16 December and defend himself against accusations of being caught flat-footed; but also to emphasize that Montgomery’s command of US forces was purely temporary. This prompted

the

Daily Mail

to bang Montgomery’s drum in the most provocative way, once more demanding that he be made land forces commander. The transatlantic press war began all over again with renewed ferocity.

Churchill was appalled.

‘I fear great offence has been given to the American generals,’

he wrote to his chief military assistant General Ismay on 10 January, ‘not so much by Montgomery’s speech as by the manner in which some of our papers seem to appropriate the whole credit for saving the battle to him. Personally I thought his speech most unfortunate. It had a patronising tone and completely overlooked the fact that the United States have lost perhaps 80,000 men and we but 2,000 or 3,000 … Eisenhower told me that the anger of his generals was such that he would hardly dare to order any of them to serve under Montgomery.’ Eisenhower later claimed that the whole episode caused him more distress and worry than any other during the war.

While Eisenhower’s emissaries, Air Chief Marshal Tedder and General Bull, were still struggling to get to Moscow, Churchill had been corresponding with Stalin about plans for the Red Army’s great winter offensive. On 6 January he had written to the Soviet leader, making clear that the German offensive in the Ardennes had been halted and the Allies were masters of the situation. This did not stop Stalin (and Russian historians subsequently) from trying to claim that Churchill had been begging for help. Roosevelt’s communication of 23 December, talking of an ‘emergency’, might have been seen in that light with rather more justification, but Stalin liked to take every opportunity to make the western Allies feel guilty or beholden to him. And he would play the same card again at the Yalta conference in February.

Stalin pretended that the major offensives westwards from the Vistula on 12 January and north into East Prussia the next day had been planned for 20 January, but that he had brought them forward to help the Allies in the Ardennes. The real reason was that meteorological reports had warned that a thaw would set in later in the month, and the Red Army needed the ground hard for its tanks. All of Guderian’s fears about the German ‘house of cards’ collapsing in Poland and Silesia were to be proved justified. Hitler’s Ardennes adventure had left the eastern front utterly vulnerable.

22

Counter-Attack

Patton’s impatience to start the advance from round Bastogne was soon frustrated. Remer proclaimed the efforts of the

Führer Begleit

‘a defensive success

on 31 December and estimated that they had destroyed thirty American tanks’. The Germans were left unmolested that night. This allowed them to form a new line of defence, which ‘astonished us eastern front warriors very greatly’. Yet Remer acknowledged that the inexperienced American 87th Infantry Division had fought well. ‘They were excellent fighters and had a number of commandos who spoke German and came behind our lines where they were able to knife many of our guards.’ There is, however, little confirmation of such irregular tactics from American sources. But since Remer’s tanks and assault guns were down to less than twenty kilometres’ worth of fuel, he ‘radioed Corps [headquarters] that we were fighting our last battle, and that they should send help’.

On the eastern flank, the 6th Armored Division passed through Bastogne on the morning of 1 January to attack Bizôry, Neffe and Mageret, where so many battles had been fought in the early days of the encirclement. The equally inexperienced 11th Armored Division, working with the 87th Infantry Division on the south-west side of Bastogne as part of Middleton’s VIII Corps, was to advance towards Mande-Saint-Etienne, but came off badly in a clash with the 3rd Panzergrenadiers and the

Führer Begleit

.

‘The 11th Armored is

very green and took unnecessary casualties to no effect,’ Patton recorded. The division was shaken by the shock of battle. Even its commander was thought to be close to cracking

up under the strain, and officers seemed unable to control their men. After bitter fighting to take the ruins of Chenogne on 1 January, about sixty German prisoners were shot.

‘There were some unfortunate

incidents in the shooting of prisoners,’ Patton wrote in his diary. ‘I hope we can conceal this.’ It would indeed have been embarrassing after all the American fulminations over the Malmédy–Baugnez massacre.

Tuesday 2 January was

‘a bitter cold morning’

, with bright clear skies, but meteorologists warned that bad weather was on the way. Manteuffel appealed to Model to accept that Bastogne could no longer be taken. They had to withdraw, but Model knew that Hitler would never agree. Lüttwitz also wanted to pull back east of the River Ourthe, as he recognized that the remnants of the 2nd Panzer-Division and the Panzer Lehr were dangerously exposed at Saint-Hubert and east of Rochefort. In the

Führer Begleit

,

battalions were down to less than 150 men and their commanders were all casualties. Remer claimed that there was not even enough fuel to tow away the damaged tanks. The answer from the Adlerhorst

was predictable. Hitler insisted on another attempt on 4 January, promising the 12th SS

Hitler Jugend

and a fresh Volksgrenadier division. He now justified his obstinacy on the grounds that, although his armies had failed to reach the Meuse, they had stopped Eisenhower from launching an offensive against the Ruhr.

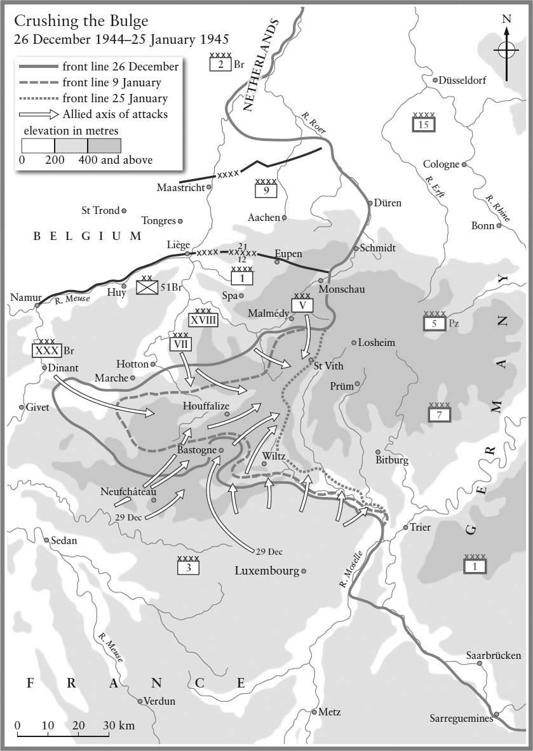

The First Army and the British XXX Corps began the counter-offensive on 3 January as planned. Collins’s VII Corps, led by the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions, attacked between Hotton and Manhay, with Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps on its eastern flank. But the advance was very slow. The weather conditions had worsened with snow, ice and now fog again. Shermans kept sliding off roads. No fighter-bombers could support the advance in the bad visibility. And the German divisions, although greatly reduced, fought back fiercely.

Although the 116th Panzer-Division was forced back from Hotton, German artillery, even while withdrawing,

‘continued to pour destruction’

on the town. The theatre, the school, the church, the sawmill, the Fanfare Royale

café, the small shops on the main street, the houses and finally the Hôtel de la Paix were smashed. The only structure undamaged in Hotton was the bandstand on an island in the Ourthe river, and its roof was riddled by shell fragments.

On 4 January, Manteuffel launched a renewed assault on Bastogne as ordered, but this time his troops came in from the north and north-east led by the 9th SS

Hohenstaufen

and the SS

Hitler Jugend

supported by two Volksgrenadier divisions. In the north near Longchamps the 502nd Parachute Infantry, which had just fought a protracted battle, received a lucky break. A German panzergrenadier from the SS

Hohenstaufen

became lost in the snow-bound landscape. Seeing a soldier standing in a foxhole with his back to him, he assumed he was German, went up and tapped him on the shoulder to find out where he was. The paratrooper, although taken by surprise, managed to knock him down and overpower him. During interrogation, it transpired that the German prisoner was a company runner, carrying all the details of the attack planned for the following morning. He even volunteered the exact position of the assembly areas for 04.00 hours. Since the information seemed too good to be true, the regimental interrogator suspected that he must be planting disinformation, but then began to realize that it might well be genuine. The 101st Airborne headquarters was informed, and every available field artillery battalion and mortar platoon stood ready.

The attack of the SS

Hohenstaufen

against the 502nd Parachute Infantry was severely disrupted in the north. But the offensive against the Bastogne pocket, as it was now termed, hit the 327th Glider Infantry round Champs, the scene of the battle on Christmas Day, and was especially ferocious in the south-west. The 6th Armored Division, attacked by the

Hitler Jugend

, was close to breaking point; and after one battalion collapsed, a general withdrawal took place, losing Mageret and Wardin. A complete collapse was prevented by massive artillery concentrations.

Even the experienced 6th Armored had lessons to learn. A lot of the fog of war on the American side came from the simple failure of commanders at all levels to report their position accurately.

‘Units frequently make errors

of several thousand yards in reporting the location of their troops,’ a staff officer at the division’s headquarters observed. And on a more general perspective he wrote that American divisions were ‘too sensitive to their flanks … they often do not move unless someone else is protecting their flanks when they are quite capable of furnishing the necessary protection themselves’.

‘If you enter a village

and you see no civilians,’ another 6th Armored officer advised, ‘be very very cautious.

It means that they have gone to ground in their cellars expecting a battle, because they know German soldiers are around.’

Many soldiers closed their minds to the suffering of the Belgians as they focused on the priority of killing the enemy. Those who did care were marked for life by the horrors that they witnessed. Villages, the principal targets for artillery, were totally destroyed. Farms and barns blazed. Women and children, forced out into the snow by the Germans, were in many cases maimed or killed by mines or artillery from both sides, or simply gunned down by fighter-bombers because dark figures against the snow were frequently mistaken for the enemy. GIs found wounded livestock bellowing in pain, and starving dogs chewing at the flesh of lacerated cows and horses even before they were dead. Water sources were poisoned by white phosphorus. The Americans did what they could to evacuate civilians to safety, but all too often it was impossible in the middle of a battle.

West of Bastogne, the 17th Airborne Division took over from the 11th Armored Division on 3 January. The 11th Armored had advanced just ten kilometres in four days, at the cost of 661 battle casualties and fifty-four tanks. The newly arrived paratroopers appeared to fare little better in their first action.

‘The 17th Airborne, which attacked this morning,’

Patton wrote in his diary on 4 January, ‘got a very bloody nose and reported the loss of 40% in some of its battalions. This is, of course, hysterical.’

The 17th Airborne, fighting towards Flamierge and Flamizoulle on the western edge of the Bastogne perimeter, was up against the far more experienced

Führer Begleit

and the 3rd Panzergrenadier-Division.

‘We have had replacements

who would flop down with the first burst of enemy fire and would not shoot even to protect others advancing,’ an officer complained.

American advice came thick and fast.

‘The German follows a fixed form

. He sends over a barrage followed by tanks, followed by infantry. Never run, if you do you will surely get killed. Stick in your hole and let the barrage go over. Stick in your hole and let the tanks go by, then cut loose and mow the German infantry down.’ ‘Don’t go to a white flag. Make the Germans come to you. Keep the Krauts covered.’ Officers also found that their men must be trained what to do when shot in different parts of the body, so that they could look after themselves until a medic

arrived. ‘Each man takes care of himself until the medical men arrive.

No one

stops the fight to help another.’ Yet badly wounded men left in the snow without help were unlikely to survive more than half an hour.

The 17th Airborne Division had a tank battalion manned entirely by African-American soldiers attached to it.

‘Our men had great confidence in them,’

a colonel reported. ‘We used the tanks to protect our infantry moving forward. The tanks would come first with the doughboys riding on them and following in squad columns [behind them]. Selected men were in the last wave, tail end of the company, to knock off Jerries in snow capes. The Jerries in snow capes would let the tanks and bulk of the infantry pass, then rise up to shoot our infantry in the back, but our “tail enders” ended that.’

When they captured a position, they usually found that the ground was frozen so hard that it was impossible to dig in. The division decided that they needed to use their 155mm guns to blast shellholes on an objective or piece of ground to be occupied, so that foxholes could be prepared rapidly. With so much to learn against such hardened opponents, it was hardly surprising that the 17th Airborne had such a baptism of fire.

‘The 17th has suffered a bloody nose,’

12th Army Group noted, ‘and in its first action lacks the élan of its airborne companions.’ But there were also examples of outstanding heroism. Sergeant Isidore Jachman, from a Berlin Jewish family who had emigrated to the United States, seized a bazooka from another soldier who had been killed, and saved his company by fighting off two tanks. He was killed in the process and was awarded a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor.

The 87th Infantry Division to the west was not making any better progress, having come up against a Kampfgruppe

from the Panzer Lehr. There were constant complaints about soldiers being far too trigger-happy and wasting ammunition. A sergeant in the 87th Division described how he

‘saw a rifleman

shoot a German and then empty his gun and another clip into him although it was obvious that the first shot had done the job. A 57mm gun fired about forty rounds into a house suspected of having some Germans in it. Practically all were A[rmor] P[iercing] shells and fired into the upper floors. The Germans were in the basement and lower floor and stayed there until we attacked.’

The 87th Division, despite Remer’s compliments on their fighting prowess, suffered all the usual faults of green troops. Men froze under

mortar attack instead of running forward to escape it. And when soldiers were wounded, several would rush over to help them instead of leaving them to the aid men following on behind. Unused to winter warfare, the 87th and the 17th Airborne suffered many casualties from frostbite. Men were told to obtain footwear which was two sizes too big and then put on at least two pairs of socks, but it was a bit late for that once they were already in action.

Middleton was utterly dejected by the performance of the inexperienced divisions. Patton was furious: his reputation was at stake. He was even more convinced that the counter-attack should have been aimed at the eighty-kilometre base of the salient along the German frontier. He blamed Montgomery, but also Bradley who was

‘all for putting new divisions in the Bastogne fight’

. He was so disheartened that he wrote: ‘We can still lose this war … the Germans are colder and hungrier than we are, but they fight better. I can never get over the stupidity of our green troops.’ Patton refused to recognize that the lack of a good road network at the base of the salient, together with the terrain and the atrocious winter weather which frustrated Allied airpower, meant that his preferred option would probably have stood even less chance of rapid success.

The advance of the counter-offensive in the north fared only slightly better, even with the bulk of the German divisions switched to the Bastogne sector. There was nearly a metre of snow in the region and temperatures had dropped to minus 20 Centigrade.

‘Roads were icy

and tanks, despite the fact that gravel was laid, slipped off into the sides, destroying communication set-ups and slowing traffic.’ The metal studs welded to the tracks for grip wore off in a very short time. In the freezing fog, artillery-spotting Cub planes could operate for only part of the day, and the fighter-bombers were grounded. The 2nd Armored Division found itself in an ‘extremely heavy fight’ with the remnants of the 2nd Panzer-Division.

‘A lucky tree burst

from an 88-mm shell knocked out between fifty and sixty of our armored infantry, the largest known number of casualties’ from a single shell. But

‘Trois Ponts was cleared

as was Reharmont and by nightfall the line Hierlot–Amcomont–Dairmont–Bergeval was reached,’ First Army noted. The 82nd Airborne Division took 500 prisoners.