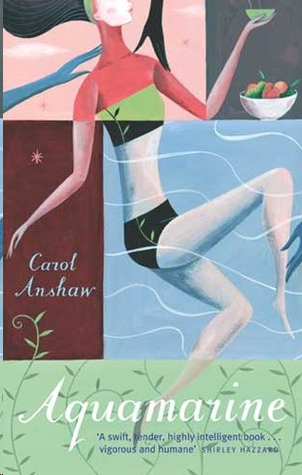

Aquamarine

Table of Contents

July 1990 New Jerusalem, Missouri

July 1990 Venus Beach, Florida

Copyright © 1992 by Carol Anshaw

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anshaw, Carol.

Aquamarine / Carol Anshaw.

p. cm.

ISBN

0-395-58562-7

ISBN

0-395-87755-5 (pbk.)

I. Title.

PS

3551.

N

7147

A

94 1992 91-27963

813'.54—dc20 CIP

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Robert Overholtzer

QUM

10 9 8 7 6

Note: The actual hundred-meter freestyle event at the 1968 Olympics had its own setting, and was won and lost by real-life women, who don’t enter into this story. All characters and events in these pages are purely imagined.

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to quote from the lyrics of the following songs: “Cheek to Cheek.” © Copyright 1935 by Irving Berlin. © Copyright renewed. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Lyric excerpt reprinted by permission of Irving Berlin Music Company. “Open All Night,” copyright © 1982 by Bruce Springsteen/ASCAP. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

For Barbara

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank my agent Jean Naggar, my editor Janet Silver, and the Ragdale Foundation.

Also, my deep appreciation to Rebecca Chekouras, Lyn DelliQuadri, Chap Freeman, Chris Paschen, Johanna Steinmetz, Claire Whitaker and—always and most especially—Mary Kay Kammer.

Freestyle

October 1968 Mexico City

F

OR A FEW

supersaturated moments, Jesse feels and sees and smells and hears everything. The crushing heat, the Mexican sky white with a flat sun, pressing like an iron against the roll of her shoulders. The rising scent of chlorine and baby oil and something that’s not sweat exactly, but an aquatic analog, something swimmers give off in the last few minutes before an event, a jazzy mix of excitement and fear and wanting. The crowd, riled up as though they are going to swim this race themselves.

Except for her godmother, who sits in the stands, unruffled, unflapped—a midwestern Buddha, here by way of two days and a long night on a Trailways bus from Missouri. With her is Jesse’s brother, bouncing a little in his seat, twiddling his hands like a haywire backup singer, a Temptation gone kaflooey. There’s so much else going on, though, that for once he draws no particular attention.

Down at pool level with Jesse is Bud Freeman, coach of the American women’s team, a crew-cut fireplug several inches shorter than Jesse, at the moment casually peppering her arm with light jabs of his thick finger, reminding her that Marty Finch is a splash-out-and-die girl, not to worry about her in the first fifty meters. His mouth is so close to Jesse’s face she can smell his breath, which is like oranges. She nods and tongues the insides of her goggles and looks over his shoulder at Marty, who is doing leg stretches against the next starting block, not looking at Jesse. Which is smart. Jesse shouldn’t be looking at her either, not now.

Jesse stands next to the Lane 4 starting block. She’s still nodding at whatever Bud is saying, although she has stopped listening, doesn’t really need to. She has swum this race in her head every day since she was fourteen. For most of those three years’ worth of days, her body has been through fifteen thousand meters, so it will know on its own precisely how to take these hundred. Today she will really just be going along with herself for the ride.

It’s time to take to the blocks. In this instant, the wave she was riding—absorbing everything at once—crashes onto the shore of her self, and she whites out into a space at her dead center. She loses Bud, the crowd, the sun. All there is is her and the water stretching out in front of her, to be gotten through. Fifty meters up. Flip. Fifty meters back. A quick trip.

She stretches the strap of her goggles around the back of her head, lets it snap. Fiddles with the eye cups, tugs at the strap ends until she’s sure she has a seal. She crouches and swings her arms behind her, then forward, just short of losing her balance. She’s ready. She doesn’t even need to see the starter to know he’s raising the pistol. She can feel the event approaching, feel herself moving into it.

“Swimmers, take your marks.” The metallic command comes through the public address horns, taking the event out of the dimension of not-happening, onto the plane of about-to-happen.

She hyperventilates to expand her lungs, flattens her soles against the roughed surface of the block. Now comes the critical moment, the one in which she needs to leave even herself behind and become purely what she can do, translate matter into energy, become velocity. In the hundreds of events she has swum on the way to this one, this split second in which she can see the race ahead completely, and see herself winning it, has given her an edge.

This time, though, the power of belief slips away, just a little. Just for the microslice of the second it takes for her to look over at Marty. Who does, for a flash instant, look back. But, through her goggles and then Marty’s, and with the sun behind her blacking her out, Jesse can’t read her face. She is still trying to decipher it, to pull some important message off it, still trying to link today with last night, to figure out the connection between those events and this one. While she is temporarily lost in this constellation of fear and exhilaration and squeezed hope, the starter’s pistol, which she is supposed to respond to instinctively, as though it’s inside her, goes off in some very faraway place. Taking her completely by surprise.

And so Jesse Austin leaps out, hangs suspended for a freeze-frame moment, and enters Olympic waters one tenth of a second later than she should. She can’t curse the lapse. There’s no time. The next minute is an aquamarine blur. The color shattered into a million wavy panes as the water prisms the sunlight that hits the pool bottom. Aquamarine and the deep blue of the wide stripe she follows down the center of the lane, tucking into her flip turn, where the stripe dead-ends in a T. The touch of painted concrete against the balls of her feet as she pushes off. And then the last fifty. She knows she’s swimming fast, maybe faster than she ever has. She feels an infinitesimal difference. It’s as though the water has given in, is letting her through.

And then, there’s the slick slap of tile on the palm of her hand as she finishes where she started. She comes up fast and flushed and eating air. She corkscrews out of the water, ripping off her goggles, looking around wildly for signs. To her left, in Lane 5, Marty has also touched. She’s pulling off her cap with a rubbery squeak, bending back, her Hair catching the water like white seagrass. Jesse watches this for a moment; it’s a part of the too much happening all at once. She’s still looking for the word to come down.

Then Bud is crouching on the rim of the pool just above her, shaking his head, holding up two fingers. She has come in second, taken the silver. Won something, but it’s the loss that hits her first. She feels as though great weights are dragging her under. She looks over and watches Marty catch the good news from Ian Travers, the Australian coach. She has taken the gold. She’s tossing her cap and goggles into the air and smiling with her whole body. And then she looks around and reaches outside the perimeter of her victory, over the lane markers to wrap an arm around Jesse’s shoulders. It’s a cross-chest carry of sorts, a gesture to bring Jesse up with her.

Amazingly, it works. Jesse can feel her spirit grabbing onto Marty’s, and for this moment at least believes

they’ve

won, that together they’ve beat out the competition, that the two of them are laughing together in the hilarious ozone just above the plane of regular mortals. They go under, somersault, come up, and shoot out of the water, trailing arcs of spray behind them.

Jesse feels they have attained a great height, as though glory is a wide, flat place they will inhabit forever, rather than a sharp peak that will quickly slide them down another side, to ground level. But she isn’t looking down now, only out, toward the limitless possibilities implicit in having attained this one.

She can feel their breezes rushing over her, lightly.

Skywriter

July 1990 New Jerusalem, Missouri

“S

WEETHEART

.” Neal braces himself in the kitchen doorway, rocking in and out a little as he says, “Can you close the cave? I’m almost done tallying up in the office.” His T-shirt is sweat-stuck to his rib cage. He pulls off his baseball cap and wipes his forehead with the inside of his arm. This is the hottest summer down here in anyone’s memory. It has cleared a hundred every noon for the past six days. Even the really old folks, who can usually top the present with some dramatic weather of the past, say no, this is the worst hot spell ever.

Jesse nods sure, blots a thread of perspiration from her temple, and releases her hair from the clip at the base of her neck. It whooshes out like a fan. She gathers it and reclips it tightly. “I should just get this mop cut off.”

Neal looks at her for a moment as if he sees her, but with the sound off. Then he tunes in. “Don’t think of it. Red hair’s hard to come by. Yours is your crowning glory.”

“I hope you never stop flattering me,” Jesse says, and turns to finish dissolving the lump of canned lemonade in a scarred plastic pitcher, spinning it around with a spatula. The baby inside her kicks, connecting with the handle of the spatula, knocking it out of her hand. She and Neal both look down at the gray rubber blade, centered in a puddle on the old linoleum. And then at the surprise in each other’s eyes.

“Do you think this says something about her starter personality?” Jesse says. There are moments when it hits her that she and this baby inside her have yet to meet.

“You mean, even if we send her to some fancy school and teach her which fork to use and how to address invitations, is she still going to wind up punching guys’ lights out in bars?”

“We can hope,” Jesse says. “I love the idea that she might already be a little scrapper in there.” She reaches for the roll of paper towels standing on the counter, but Neal gets there first and begins mopping up while she rinses her hands, wipes them down the skirt of her seersucker maternity smock, pushes open the screen door of the house, and steps outside.

The house started off as two mobile homes set together, but with the passing of time and the addition of a back room and a jalousied side porch and a small patch of front yard bordered by Jesse’s rosebushes, it almost passes for a real house. The roses hold it down, give it weight with their sweep of brilliant reds, hybrid tea roses tagged with names of celebrity and importance. Kentucky Derby. Dolly Parton. Chrysler Imperial. The house is set back on the property in a small stand of trees, up a roped-off dirt drive away from the cave and its visitors, out of earshot of the stalactite xylophone, which pulses “Lady of Spain” and “Que Será, Sera” up through the soles of those walking the ground above it.

The cave belongs to Neal’s family, the Pratts. They are mostly invested in traveling carnivals but have a few stationary attractions like this and Lookout Point at the western edge of the state, plus a small geyser in Arkansas. Billed as Pratt’s Caverns, it’s an old-fashioned sight. In the spring, two guys came by and tried to talk Neal into putting in a laser show. He wasn’t interested. He likes the cave fine just the way it is. He sometimes refers to it as “majestic.” One of the things about him which first caught Jesse’s notice was this capacity for corniness. He really reads the verses inside birthday cards. He sings along at concerts, and with the car radio.

This is the height of their tourist season, and in this heat, the natural coolness of the cave makes it even more attractive. Today they had more than two hundred people going through, including two tour buses of Germans early in the afternoon. The entrance has been shut for over an hour now. Before they can close up entirely, though, someone has to check to make sure all the caverns are empty. Sometimes local school kids sneak in, try to stay the night to see if the place is haunted. Once in a while, old people wander off from their tours, grow confused, get a little lost.

The steps are so worn at the center, it looks as though the stone is sagging. Jesse follows them down, holding on to the rail—something she never did before the baby. She is used to being physically reckless. Now she has to behave like a courier of valuable goods.