Appropriate Place

Authors: Lise Bissonnette

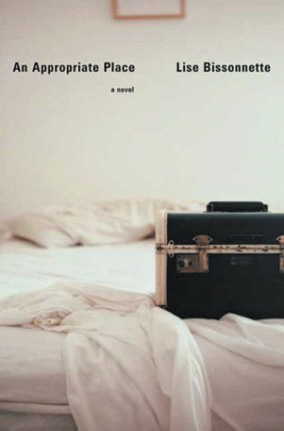

An Appropriate Place

a novel

Lise Bissonnette

Translated by Sheila Fischman

Copyright © 2001 Les Ãditions du Boréal

English translation copyright © 2002 House of Anansi Press Inc.

First published as

Un Lieu Approprié

in 2001 by Les Ãditions du Boréal

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic

piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate

your support of the author's rights.

This edition published in 2012 by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina

Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto,

ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

www.houseofanansi.com

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Bissonnette, Lise [Lieu approprié English]

An appropriate place / Lise Bissonnette. -- 1st ed.

Translation of: Un lieu approprié.

ISBN 978-1-77089-116-6 (epub)

I. Title. II. Title: Lieu approprié English.

PS8553.I877288L5313 2002Â Â Â Â Â C843'.54Â Â Â Â Â C2002-904129-5

PQ3919.2.B52L5413 2002

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing

program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the

Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

for Godefroy-M. Cardinal

One

AT THE VERY MOMENT

when Gabrielle Perron

is brushing against her chauffeur's knee, he slams on the brakes. For the last time.

The limousine comes to a halt across the pavement, the door slams and, instead of

going to open Gabrielle's, Jean-Charles becomes absorbed in a bed of begonias, a

pallid spot on the already yellow lawns on rue des Bouleaux where a single eponymous

birch tree is growing, sickly.

Gabrielle joins him just as he turns away, she sees the little calico

cat whose brains are spreading onto the white begonias, its forehead split down the

middle and its life departing through an orange smudge, its black-and-grey flecked

belly stops twitching, the eyes are already closed. Gabrielle grazes the sweating

muzzle â she who detests being kissed by a cat â but she has to put off her caress

till later.

And so all is well, despite the incident. Jean-Charles is dropping her

off one last time at 10,005 rue des Bouleaux; it was a mistake for her to sit in the

front, but the backseat was jammed with the thousand items left over when an office

is cleared out â the papers, the photos under glass, the collection of prints by

Charlène Lemire that she'd been one of the first to admire and that now, in her

home, would finally be given the softer light necessary for their silken ghosts.

There was also, wrapped in old-maidish tartan, the huge and fragile rosewood ashtray

that had belonged to a prewar premier and that the museum didn't want, nor did the

custodian of the storerooms in Parliament, where smoking was now forbidden. But

Gabrielle Perron had sat in front today to be silent in the presence of the man to

the nape of whose neck she'd been speaking for four years, his name is Jean-Charles

and he has never wavered, neither when avoiding a deer in the pitch black night nor

while driving through a demonstration in broad daylight.

All is well, he will empty out the limousine and go on his way, he

will always believe that she brushed against his knee to draw his attention to the

animal, she'll offer him a glass of water at the kitchen counter and walk him to the

fourth-floor elevator, he won't imagine that she would have stripped naked today, in

front of his brown eyes and his firm hand, in a puddle of sunlight from the living

room to which he couldn't imagine being admitted.

Jean-Charles has wadded a page of a newspaper lying on the backseat,

he wipes the bumpers of the navy Chevrolet, such a small cat can't have left any

traces. Gabrielle wonders if he too is trying to put on a brave face, but apparently

not. “We'll have to find out who the cat belongs to,” he says. She disagrees, rue

des Bouleaux is lined with identical apartment buildings, all pink bricks and

deserted white balconies, very few children there have cats, Gabrielle knows that,

for she bought the apartment because there weren't many children and she'd thought

that animals were not allowed. Instead, she sends Jean-Charles to the concierge, who

will know how to dispose of the animal and restore the line of begonias. “Her name

is Fatima,” says Gabrielle.

Plump and hefty, she is already on the doorstep, a still-young woman

whom Gabrielle pictures always sitting at a table over hams and potatoes. Between

her legs stands a little girl Gabrielle has never seen, but then, what does she

actually know about Fatima? The building is new, the hallways shiny, the garbage

cans taken out on time, there's no need for conversation.

The child cries over her little calico cat, she swallows, then she

howls, then she shrieks the tears from her throat. Her hair is too short, her eyes

are too huge, she could be an embryonic seamstress in a factory, she'll know how to

blaspheme before she reaches puberty. Like Fatima, who is shouting now in her own

language, guttural, a language of the sun but of curses too, of which Gabrielle

knows that she herself is the object. Rue des Bouleaux murmurs now like the lanes of

her childhood, when the mothers cursed one another between the clotheslines and the

boys deliberately killed all the cats, in the sheds at night.

Jean-Charles has two sons, Jean and Charles, teenagers who perhaps do

the same in their part of town with its still-lively laneways. Gabrielle sighs. She

wonders in what way the brain of a cat is less than that of a child, on the brink of

summer on rue des Bouleaux, in Laval.

She offers an apology that isn't heard, goes back and forth with

Jean-Charles from the limousine to the fourth floor, while Fatima finally drops the

little corpse into a garbage bag. The chauffeur will be entitled to a glass of

water. From the vestibule he won't be able to see the puddle of sunlight in the

living room that Gabrielle Perron will air out. Finally now, in June, she is going

home to the place where she told her life to wait for her.

There are three things to do to make the place liveable. Disconnect

the answering machine so that unknown supplicants, hearing only a ring, will

henceforth apply elsewhere. Buy flowers, potting soil and flower boxes to dress up

the balcony, because now she'll be there to water them. She'd like too some ivy that

would climb up a trellis on the east side, where the vacant lot was supposed to be

turned into a park but where, instead, small houses for small growing families had

sprouted, happy owners of garden furniture behind tall fences. But first she'll have

to learn how to grow ivy, which needs to take root somewhere. And she must arrange

the books on the shelves she'd made to measure for the guest room, with a sliding

ladder for looking at books near the ceiling, the idea comes from castles. Large

sections of shelves are still empty, for five years she has shelved only novels, art

books and the works of sociology and politics that she had underlined and thought

she'd understood in Strasbourg or Paris, that she'd brought home so proudly in her

student trunk. There was a metre of Rosa Luxemburg, by Rosa the Red herself or by

others, half that by Enver Hoxha, a very incomplete collection of

Esprit

above the complete collection of

Parti pris

and then, in alphabetical

order, the material for her thesis on palingenesis. At one glance, she can identify

the books that mattered from their spines: Madaule, locked inside his Christianity,

Poulantzas, who killed himself and Touraine, who still today talks about the change

of which she'd thought she would be the transmitter over the course of a summer like

this one, locked inside words while other brunettes were being married in white.

She'd had to reinforce the corners carefully so that the weight of her

library wouldn't rest entirely on the floor, apartments in Laval don't have the

joists that castles do. Now she will be able to put away the green papers and the

white papers and the commission reports, the books on sovereignty and federalism,

cases of them were delivered the previous week after being flung into boxes any old

way in the big office that she left without regret. She'll have to go through them

and preserve only those documents that she can recollect, that she cares about

because she contributed paragraphs or chapters to them, or because she found in them

echoes of her own developing social commitment. She'll get down to it tomorrow.

This afternoon she is still full of energy. The refrigerator is empty,

she'll have to get bread, milk, salmon from the fish store that's opened in the mall

adjacent to the highway, and maybe get some

choux à la crème

, if she has

any, from Irène, the woman who has given her own name to her white cakes. Then

she'll just have to put some Sauternes on ice, and at seven o'clock, when the sun

won't set on her balcony because it gives onto the northern side of the Rivière des

Prairies, though you can see its light dying over Montreal and its lives, for which

she is no longer responsible, she will finally begin to resemble Colette, the photo

of Colette at her window looking onto the garden of the Palais-Royal, surrounded by

faded books, adrift in her memories of lovers, and tasting the sugar as the aroma of

the last coffee wafts up.

Gabrielle Perron has no wrinkles, but she wants the time to see them

come; this summer will be perfect. Sitting on the counter is the Sico paint card,

she picked it up at the hardware store months before, thinking that she would

repaint the whites, they're turning grey in the kitchen and the living room, the

finishing is downscale in these apartments that were hastily put up as soon as the

zoning laws permitted. It will be white again, because of the paintings, which don't

tolerate colours, neither pale nor bright, but there are plenty of whites on a Sico

card, matte ones and glossy ones, ivories and velvets, orchid and lily, Adriatic

stones and Abitibi snow. Above all, she wants nothing iridescent.

She'll have to call Madeleine, but not today, even if she would enjoy

hearing her prattle away, over light wine, about the disarray of her latest

encounter â a man she met in the supermarket or at the university â whom she'll have

undressed and dressed again between midnight and dawn if he wasn't married, to whom

she'll have neglected to give her phone number. The last one was from Cambodia and

he'd been one of the rare ones who knew how to disappear discreetly, Madeleine had

even been slightly put out. In any event, on a sunny day like this she'd be at the

pool, colouring herself amber. She'll try to talk Gabrielle out of white, she

herself never wears it, it's hard on the complexion of any woman over forty.

Gabrielle Perron's Toyota, a cream one, will be cool in the

underground parking space. Not a sound from the corridor, that's another reason why

she chose to live here, with walls and an elevator so blind that you only encounter

the shadows of neighbours there, they sometimes say “hello” or “have a nice

day,”

like characters on American television, and if they know who

Gabrielle Perron is, which she doubts, they behave as if she is merely the owner of

apartment 401, with a balcony like theirs, and otherwise of no interest.

She goes to pick up her mail on the left side of the lobby. Virtually

nothing â a leaflet from a real estate agent, but Gabrielle has no interest in

selling, and an invitation to a benefit dinner for the party, which she's no longer

obliged to attend. It's nice to be able to tear them to pieces.

To be done: order paint, ivory or off-white as the clerk says, and

Gabrielle pictures millions of pigments just off the scale, prettily, around her

enormous windows, then bread, milk and finally salmon. There are no

choux à la

crème

at Irène's. She'll have to go directly home, she's always afraid of

poisoning herself with stale fish, even though they assure her that the crushed ice

in the display cases keeps it cool, it comes mainly from the Pacific, thousands of

kilometres in refrigerated trucks and who knows how many hours in the open, in those

little fish stores that are always run by boys with dark hands. What she likes about

salmon, what restores her confidence, is the pink colour that in a few moments will

burn under the broiler, a dish for a woman on her own who is elegant enough to be in

tune with the dusk, so many would gobble a piece of cheese in front of the

TV

set and mope around, waiting for night.

As she leaves the parking lot, she sees that some teenagers have put

up a booth with a large banner warning of a new famine in Ethiopia. She'd thought

the disaster was over, but you never know with desertification and global warming

and the forgotten people whose lives are no more stable than bubbles, the real story

never makes it to our newspapers. Now, at the onset of a heat wave, the young people

are selling polar bears decked out in red tuques, scarves and mittens, mounds of

them sit in big cartons, they recycle unsold Christmas stock from Eaton's, salve

your conscience for twenty dollars a shot. Gabrielle ends up with a stuffed animal

on the passenger seat, the timing is good, she'll make a gift of it to Fatima's

daughter who is her Ethiopia today, her little devastated zone in the sun.

Fatima always answers right away, as if she spends her life on the

doorstep, her concierge's apartment is tiny, you can see the ironing board jutting

out from the kitchenette into the crowded living room, where a huge aquarium fills

the entire wall on the right, to each his library. The child is in front of the

TV

set, where a half-naked woman is crackling under

the bullets of an invisible killer. Her eyes, which were weeping a while ago at the

gentle convulsions of a calico cat, are scathing. The stuffed animal won't do.

Gabrielle holds it out instead to Fatima, who is again displaying the closed smile

that she's noted for, it's part of her job description. Gabrielle hasn't earned even

a hint of forgiveness, but at least the day is slipping past a forgettable

misfortune. The garbage truck will be here at six a.m. and, after all, she couldn't

offer the little girl another cat, that would have been despicable; anyway it takes

time to get over the death of a cat, at least according to Madeleine, who's had

several and who claims that it's harder to recover from being abandoned by a cat

than by a lover.

Fatima arranges the toy with its back to the aquarium, on the armrest

of a flowered easy chair, and the mood does lighten. To connect with it, Gabrielle

talks about painting. Does she know of a painter in the vicinity? One with satisfied

customers in the building? It's not urgent, but Gabrielle has been away so much in

recent years, she's not sure where to inquire. Fatima has an accent that sounds at

once Spanish and German, at least to Gabrielle, who knows nothing but a few sounds

of the so-distant Alsace. No, she wouldn't dare to recommend anyone, but there's a

boy in 202 who did quite a few odd jobs for the owner of 404, the terrace apartment,

last month. The man seemed pleased, he'd even let the boy have the key for the day,

as long as he returned it to Fatima at five o'clock. And that's how a concierge

knows everything and nothing.