Anzac's Dirty Dozen (30 page)

Read Anzac's Dirty Dozen Online

Authors: Craig Stockings

It should also be noted that while the Australian Special Forces prevented a missile launch against Israel, the Iraqis did not actually attempt to do so. The Iraqi Army did not have any missile launchers positioned in the Australian area of operations, nor did they attempt to move any there once the war began. It can be debated that it was the skill of the Australians that deterred the enemy from moving rocket launchers into position, but this is a debate that cannot be resolved with any degree of certainty. In addition, as subsequently revealed, Iraq no longer possessed any weapons of mass destruction as it had ended, or suspended, its chemical and biological programs some time prior to the war's commencement.

An event that requires particular comment here is the Australian seizure of the al-Asad air base, a major Iraqi air force facility. This was one of the few events for which the ADF provided a detailed brief to the public and it has been used to highlight the effectiveness of Australia forces. It was also notable as it brought together for the first time Special Air Service (SAS), Commando and Incident Response Regiment soldiers, while flying above in support were RAAF fighters. What is misleading is the government's description of the base's seizure in tones that suggest an epic military feat. In reality the base was abandoned, undefended and littered with scores of inoperable Iraqi aircraft. At most, the

Special Forces had to contend with some armed looters who scattered after a few well-placed shots shooed them on their way.

24

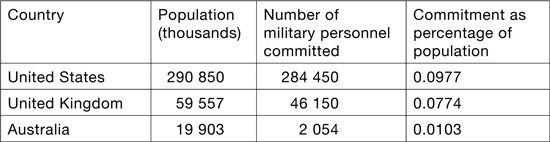

It is also possible to examine the Australian government's resolve in Iraq from the perspective of per capita commitment. When compared to the contribution of personnel by its allies, the suggestion that Australia âpunches above its weight' does not stand. The table below outlines the commitment by the three major participants in the invasion.

Commitment of Coalition military personnel to the Iraq War (Invasion Phase)

25

As would be expected, the United States provided the largest contingent to the Coalition in terms of raw numbers, and by some margin. But what is of more interest is the contribution viewed as a percentage of population. From this perspective the significance of the Australian effort becomes clear. The United States and the United Kingdom contributed personnel in roughly ten and seven times the proportion of Australia.

The commitment figure of 2054 personnel represents the ADF's entire theatre presence in the first phase of operations in Iraq and therefore includes the personnel who served with the air (C-130 transport planes, F/A-18 fighters, and PC-3 Maritime Patrol Aircraft) and maritime task groups (HMAS

Kanimbla

,

Anzac

and

Darwin

and Clearance Diving Team 3). While the above focused on Australia's ground contribution, some reflection on the nature of the larger ADF effort is warranted. While the

RAN's ships and the RAAF's planes did contribute â for example the

Anzac

provided naval gunfire support to the Royal Marines â it is hard to imagine that they were actually needed, given the sheer vastness of the sea and air armada deployed by the senior Coalition partners. It was probably only the RAAF's C130s that made a real difference to Coalition tasking, due to the perennial shortage of air transport that all modern operations seem to face. This is not to say that the personnel serving on Australia's ships and planes did not do their job, it is just that they were not essential and Australia only committed them to the operation to make up numbers, at very little additional risk, and no real benefit to the campaign's outcome as a whole.

After the fall of Baghdad to US forces on 9 April 2003, as represented by the pulling down of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, the war entered its post-conflict phase. Ironically, this phase would prove the most dangerous and challenging for the Coalition as it had to contend with a deadly insurgency while striving to establish a viable successor state to Saddam's regime. Australia never had any intention of participating in the occupation of Iraq, but it soon gave way to requests from the United States for assistance. The ADF gave this mission the name Operation Catalyst.

26

Again this analysis will focus on the ADF's ground-based contribution to Operation Catalyst. This is not to distract from the RAAF's C130 and P3C aircraft task groups or the RAN ship that continued to serve in the Middle East area of operations. Rather, it is because it was the land-based contribution that served in harm's way, on the ground, inside Iraq. Initially, Australia's assistance was quite small and took the form of a limited number of specialist personnel who deployed for a particular task and for a set period. Such tasks included, for example, assistance in the search for weapons of mass destruction, as air

traffic controllers who helped run Baghdad International Airport, and as embedded personnel in US and UK headquarters. In addition, the ADF deployed to Baghdad a security detachment to protect the Australian ambassador and staff. Australia's Middle East headquarters also moved forward to Baghdad in order to be located near the US headquarters.

Despite the initial intent to keep its presence inside Iraq as small as possible, the Australian government gave way to Coalition pressure and eventually deployed a more significant ground force. In April 2005, the ADF provided the al-Muthanna Task Group (AMTG). Its purpose was to protect a Japanese engineering group that was working in the province of the same name. The ADF also deployed the Australian Army Training Team â Iraq (AATT-I), whose task was to help the United States to train the Iraqi Army. Combined, both organisations numbered approximately 500 personnel.

27

In July 2006, AMTG relocated to neighbouring Dhi Qar Province and was renamed Overwatch Battle Group â West (OBG-W). Its new task was to provide operational overwatch to the Iraqi forces based in Dhi Qar and al-Muthanna Provinces, in case the local troops needed assistance. Australia withdrew both groups in June 2008.

28

Although an insurgency still raged across Iraq, its prosecution was not the mission of the Australians serving with AMTG/ OBG-W and AATT-I. Instead, their tasks were to train Iraqi soldiers and officers, and provide operational overwatch in both provinces, the latter a requirement they were never called upon to perform. Countering the insurgents was the job of the other Coalition forces that operated in these provinces, principally the American troops who guarded Main Supply Route Tampa, a key logistical corridor which traversed Dhi Qar. Instead of an aggressive pursuit of insurgents, the Australians adopted a defensive posture, a policy which allowed them to mitigate risk and thereby

avoid casualties. The Australians could and did defend themselves if fired upon, but seeking trouble was someone else's business.

29

Moreover, Dhi Qar and al-Muthanna proved to be among the quietest of Iraq's provinces, and the first to convert to local control. During the course of the war, Coalition forces suffered 99 and eight fatalities in these two provinces respectively. During the period in which the Australians were present, there were only five deaths as a result of hostile fire in Dhi Qar and none at all in al-Muthanna. In fact, both provinces were backwaters. The areas where the insurgency was most active were Basra to the south, al-Anbar to the west, or in Baghdad and its environs. Only the Kurdish regions of the far north were less dangerous. That said, it must still be recognised that threats did exist. Improvised explosive devices were used in Dhi Qar and al-Muthanna, and indeed a number of Australians were wounded in attacks. In addition, rockets did strike the Australian camp at Tallil, which resulted in the deaths of one Romanian and four US soldiers.

30

But such events were comparatively rare, and an Australian risk assessment that needed to include criminal activity, unexploded ordnance left over from the 1991 and 2003 wars, and road traffic accidents did not suggest an area of operations of exceptionally high danger. The characterisation of the Australian area as a ânon permissive battlespace' only served to undercut any claim that Australia punched above its weight in Iraq.

31

While casualty figures are an imprecise measure of how committed a country is to a military operation, they are indicative. As the United States bore the worst of the combat in the invasion of Iraq and the subsequent insurgency, it is not surprising that it also suffered the greatest number of fatalities: 4462 as of mid-2011. The United Kingdom's loss of 179 personnel was smaller, but still considerable. By contrast, the ADF lost just two soldiers during its entire involvement in the Iraq War, and both

deaths were non-battle related.

32

That Australia in a military commitment that lasted more than six years and involved over 20 000 personnel can suffer just two fatalities is a great outcome for the organisation and those who serve in it. It is, however, so extraordinary an achievement that it is hard to avoid the suggestion that Australia's commitment to the war was not as robust as that of its allies, and that while the ADF maintained a presence in the Coalition, the inescapable conclusion is that the policy of its deployed forces was to avoid taking any risks.

33

At the time of writing, Australia has lost 27 soldiers in the ongoing war in Afghanistan. These personal tragedies do suggest that Australia is attempting to contribute more in a combat sense to the US-led Coalition there than it did in Iraq. Australia was also one of the first countries to join the United States in attacking al-Qaeda and their Taliban protectors, and its Special Forces troops served with distinction in the war's opening phase in 2001 and 2002. The soldiers of the Australian SAS received particularly high praise for their performance during Operation Anaconda in March 2002, when they saved a party of US soldiers from two downed Chinook helicopters who were in danger of being overrun.

34

US personnel who got to know the Australian Special Forces described them in glowing terms, calling them âpros' and the âhardest looking men in Bagram'.

35

After working with the Australian SAS, the then Brigadier General James Mattis remarked, âwe Marines would happily storm Hell itself with your troops'.

36

Australia withdrew the SAS from Afghanistan in 2002 in order to have them available for the war with Iraq, and the nation did not return a field force to Afghanistan until September 2005. By 2011 this deployment had grown to approximately 1550 personnel supported by a further 800 serving elsewhere in the Middle East. The operational name given to the Australian

contribution to the war in Afghanistan is Operation Slipper.

Since re-engagement in 2005, the Australian area of operations has been Uruzgan Province in Afghanistan's south-east. The ADF contingent's mission is to train and mentor the Afghan National Army's 4th Brigade, build the capacity of the Afghan National Police in the province, and improve the capacity of the provincial government to deliver essential services to the population. In addition, the Australian Special Operations Task Group's mission is to disrupt insurgent operations and supply routes in the region. Based outside of Afghanistan but providing support to Operation Slipper are RAAF transport and surveillance elements, a detachment of gunners serving with the British Army in Helmand Province, embedded personnel serving on NATO and US staffs, as well as a RAN major fleet unit operating in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea.

37

In assessing the role of the ADF in the war in Afghanistan it is not yet possible to examine it from the perspective of outcomes achieved. Even the comparison of Australian accomplishments with those of other Coalition partners is problematic due to the limited information available. Moreover, there is considerable doubt among defence thinkers that Australia and its partners are even pursuing an achievable strategic goal. For example, the Provincial Reconstruction Team has completed an impressive list of reconstruction projects, yet the jury is still out on the effectiveness of such aid programs in winning the âhearts and minds' of a people. Operational outcomes, therefore, are still too undecided to serve as useful guides for determining the mission's overall success or failure.

It is necessary, therefore, to look at the Australian role in the war in Afghanistan not in isolation but rather in comparison with that of a defence force of another country. In its commitment to this conflict, Canada offers useful points of comparison

with Australia. Canada and Australia share a common language, cultural values and history, and both rely on mineral extraction for much of their national wealth. Each country also has a close military relationship with the United States. While Canada is approximately 50 per cent larger than Australia in population, its defence expenditure and size of its armed forces are roughly the same. In 2009, Canadian and Australian defence expenditure were also almost identical at US$19 575 and US$19 515 million respectively, while the number of full-time personnel fielded by the Canadian forces was 66 000 versus 57 000 for the ADF.

38