Antony and Cleopatra (58 page)

Read Antony and Cleopatra Online

Authors: Colleen McCullough

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Historical Fiction, #Historical, #Romance, #Antonius; Marcus, #Egypt - History - 332-30 B.C, #Biographical, #Cleopatra, #Biographical Fiction, #Romans, #Egypt, #Rome - History - Civil War; 49-45 B.C, #Rome, #Romans - Egypt

Emboldened, he sought out Cleopatra and tried to tell her how he felt, but it fell out as he had expected. She laughed at him, pinched his cheek, kissed him lovingly, and told him to run away and do the things boys of his age should. Hurt, isolated, with no one he felt he could turn to, he moved further from his mother mentally and began not to come to dinner. That he might have gone to Antony never occurred to him; he saw Antony as Cleopatra’s quarry, didn’t think that Antony’s response would be any different from hers. The dinner omissions became more numerous in exact proportion to Cleopatra’s increasingly remorseless browbeating of her husband, whom she treated, Caesarion thought, more like a son than a partner in her enterprises.

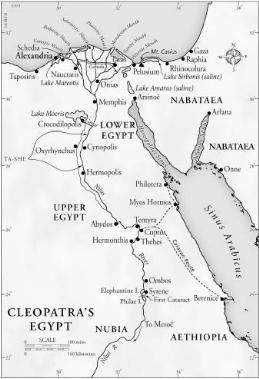

There were, however, enjoyable days, sometimes longer periods; in January the Queen took

Philopator

out of his shed and sailed down Nilus to the First Cataract, even though it was not the right season to inspect the Nilometer. For Caesarion, a wonderful trip. He had made the journey before, but when he was younger; now he was fully old enough to appreciate every nuance of the experience, from his own godhead to the simplicity of life along the mighty river. The facts were stored away; later, when he was Pharaoh in truth, he would give these people a better life. At his insistence they stopped in Coptus and took the overland caravan route to Myos Hormus on the Sinus Arabicus; he had wanted to take the longer path to Berenice, far down the Sinus, but that Cleopatra refused to do. From Myos Hormus and Berenice the Egyptian fleets set out for India and Taprobane, here they returned bearing their cargoes of spices, peppercorns, ocean pearls, sapphires, and rubies. Here too the Horn of Africa fleets were harbored; they carried ivory, cassia, myrrh, and incense from the African coast around the Horn. Special fleets brought home gold and jewels sent overland to the Sinus from Aethiopia and Nubia; the country was too rugged and Nilus too convulsed by cataracts and rapids to use the river.

On their return journey, sailing now on the current, they paused at Memphis, entered the precinct of Ptah, and were shown the treasure tunnels that branched out a long way toward the pyramid fields. Neither Caesarion nor Antony had seen them, but Cha’em, their guide, was careful not to let Antony see where and how the entrance was accessed; he was led blindfold, and thought it a great joke until, his eyes freed, he beheld the wealth of Egypt. For Caesarion it was an even bigger shock; he hadn’t begun to grasp how much there was, and spent the rest of the long journey marveling at his mother’s parsimoniousness. She could afford to feed all of Alexandria to the point of gluttony, and yet she grumbled at his pathetic little free grain dole!

“I do not understand her,” he muttered to Antony as

Philopator

sailed into the Royal Harbor.

A remark that sent Antony into fits of laughter.

The conquest of Illyricum was to take three years, but the first of them, that same year Antony was supposed to have been senior consul, was the hardest, simply because it took a year to understand how to go about the business handily. As with any enterprise of Octavian’s, it was meticulously planned insofar as any military venture could be. Governor of Italian Gaul for the duration of the Illyrian campaign, Gaius Antistius Vetus was to deal with the restless tribes living in the Vale of the Salassi on the northwestern frontier; though many hundreds of miles away from Illyricum, Octavian wanted no part of Italian Gaul at the mercy of barbarian tribes, and the Salassi were still a nuisance.

The actual Illyrian campaign was divided into three separate theaters: one on the sea, two on the land.

Back in favor, Menodorus was given command of the Adriatic fleets; his job was to scour the islands off Istria and Dalmatia and sweep the Liburnian pirates from the sea. Statilius Taurus was given command of the group of legates who drove east from Aquileia over the pass of Mount Ocra toward the town of Emona and, eventually, the headwaters of the Savus River. Here dwelled the Taurisci and their allies, who perpetually raided Aquileia and Tergeste. Agrippa was to strike southwest from Tergeste into the lands of the Delmatae and the town of Senia; from that point Octavian would assume the command himself, turn east, cross the mountains, and descend upon the Colapis River. Once on the river, he would march to Siscia, at the confluence of the Colapis and the Savus. This was the wildest, least-known country.

The propaganda commenced well in advance of the campaign, for Illyricum’s subjugation was a part of Octavian’s scheme to make it plain to the people of Italia and Rome that he, and he alone, cared about their safety as much as he cared about their welfare. Once Italian Gaul was freed from all outside threat, the entire alp-fringed Italian haunch would be as safe as the leg.

Leaving Maecenas to govern Rome under the indifferent eye of the consuls, Octavian sailed from Ancona to Tergeste, and thence rode overland to join Agrippa’s legions as their nominal commander-in-chief. Illyricum came as a shock; used though he was to thick forests, these were, he sensed, more akin to the leafy wastelands of the German forests than anything Italia or other civilized places could produce. Wet, gloomy, dense beyond imagination, the gigantic trees stretched on forever, the rugged ground beneath their canopy so stripped of light that only ferns and fungi grew there. The people, Iapudes now, hunted deer, bear, wolf, aurochs, and wildcat, some for food, some to safeguard their pathetic villages. Only in a few clearings did they break the soil to grow millet and spelt, the source of pallid bread. The women kept a few chickens, but the diet was monotonous and not particularly nourishing. Trade, which flowed through the sole emporium, Nauportus, consisted in bearskins, fur, and gold panned from rivers like the Corcoras and the Colapis.

He found Agrippa at Avendo, which had surrendered at sight of the legions and so much formidable siege equipment.

Avendo was to be their last peaceful submission; as the legions began to cross the Capella ranges, the forests proved to contain an undergrowth of shrubs and bushes too dense to penetrate without physically hacking a path.

“No wonder,” said Octavian to Agrippa, “that countries much farther away from Italia than Illyricum have been pacified while Illyricum remains unconquered. I think even my divine father would have blanched at this terrible place.” He shuddered. “We are also marching—if I may use that word ironically—at some risk of attack. The undergrowth makes it impossible to recognize the site of an ambush ahead of us.”

“True,” said Agrippa, waiting to see what Caesar suggested.

“Would it help if we sent some cohorts up on to the ridges on either side of our progress? They might have a chance of spotting raiders crossing a clearing.”

“Good tactics, Caesar,” Agrippa said, pleased.

Octavian grinned. “Didn’t think I had it in me, did you?”

“I never underestimate you, Caesar. Too full of surprises.”

The advance cohorts on the ridges foiled several ambushes; Terpo fell, Metulum lay ahead. This was the biggest settlement in the area, with a well-fortified wooden stronghold atop a two-hundred-foot crag. Its gates were shut, its inhabitants defiant.

“Think you can take it?” Agrippa asked Octavian.

“I don’t know, whereas I do know you can.”

“No, because I won’t be here. Taurus is in a dilemma—is he to keep going east, or turn north toward Pannonia?”

“As Rome needs both east and north pacified, Agrippa, you’d better go and make up his mind for him. But I will miss you!”

Octavian surveyed Metulum carefully, and decided that his best line of attack was to build a mound from the valley floor all the way up to the log walls two hundred feet above. The legionaries dug away cheerfully, piled up the rock-larded earth to the specified height. But the Metulans, who had captured siege engines and apparatus from Aulus Gabinius years before, promptly used their excellent Roman spades and shovels to undermine the mound; riddled with tunnels, it fell apart. Octavian re-erected it, but not flat against Metulum’s cliffs. Now it reared free, shored up on every side by stout planks. A second mound was raised alongside it. Able to turn their hands to anything, legionary artificers began constructing a wooden framework between the fortress cliffs and the two Roman mounds; when the scaffolding reached the height of the walls, it would carry two planked bridges from each mound to those walls. Each of the four gangways was wide enough to allow eight soldiers abreast, which would lend the assault great and immediate manpower.

Agrippa came back just in time to witness the attack upon Metulum’s walls, and toured the siegeworks thoughtfully.

“Avaricum on a tiny scale, and flimsier by far,” he said.

Octavian looked devastated. “I did it wrong? It isn’t what is needed? Oh, Marcus, let us not waste lives! If it isn’t right, tear it down, please! You’ll think of a better way.”

“No, no, it’s fine,” Agrippa soothed. “Avaricum was a city with

murus Gallicus

walls, and Divus Julius’s log platform took a month to build, even for him. This will suffice for Metulum.”

For Octavian, much depended upon this Illyrian campaign, even above and beyond its political importance. Eight years had passed since Philippi, yet despite the campaign against Sextus Pompey, people still sneered that he was a coward, too afraid to face enemy troops. The asthma had finally disappeared, and he thought its recurrence unlikely in surroundings like these, wet and wooded. He believed that marriage to Livia Drusilla had cured him, for he remembered that his divine father’s Egyptian physician, Hapd’efan’e, had said a happy domestic life was the best recipe for a cure.

Here in Illyricum he had to forge a new reputation—as a brave

soldier

. Not as a general, but as one who fought in the front lines with sword and shield, the same way his divine father had on many occasions. Somewhere he had to find an opportunity to be a front-line soldier, but so far he hadn’t succeeded. The deed had to be spontaneous and dramatic, visible to those who fought around him—something truly remarkable, worthy of being recounted from legion to legion. If that happened, he would be free of the canard of Philippi. Display battle scars for all to see.

His chance came when the attack on Metulum got under way at dawn on the day following Agrippa’s return. Desperate to be rid of the Roman presence, the Metulans, undetected, had mined a way out of their citadel and emerged at the base of the scaffolding in the middle of the night. They sawed through the main support beams, but not completely; it was the weight of the legionaries, massing on the gangways, that caused the collapse.

Three of the four bridges broke and fell, soldiers plummeting to the valley floor in dozens. By happy chance, Octavian was close to the remaining bridge. When his troops faltered and began to retreat, he seized a shield, drew his sword, and ran to their front rank, halfway across.

“Come on, boys!” he shouted. “Caesar’s here, you can do it!”

The sight of him worked wonders; cheering, shrieking their war cry to Mars Invictus, the troops rallied and, with Octavian at their head, pounded along the gangway. They almost made it. Right under the wall the bridge gave way with a crackling roar; Octavian and the soldiers directly behind him fell into the valley.

I cannot die! a part of Octavian’s mind kept repeating, but it was a cool mind still. As he tumbled off the structure he grabbed for the end of a shattered strut, held it for long enough to spot another below him, and so went down the two hundred feet in stages. His arm felt wrenched out of its socket, his hands and forearms were porcupined with splinters, and somewhere his right knee took a frightful blow, but when he wound up on the mossy ground buried under timber, he was still very much alive.

Frantic men tore the heap apart, screaming to their horrified companions that Caesar was injured but not dead. As they dragged him out, handling the right leg as gently as they could, Agrippa arrived, white-faced.

Octavian gazed up at the ring of faces around him, consumed with pain, determined not to be a sissy and show it.

“What’s this?” he demanded. “What are you doing here, Agrippa? Build more bridges and take this wretched little fortress!”

No stranger to Octavian’s nightmares about cowardice, Agrippa grinned. “Typical!” he roared in a stentorian voice. “Caesar’s badly wounded, but our orders are to take Metulum! Come on, boys, let’s start again!”

The battle was over as far as Octavian was concerned; he was put on a stretcher and carried to the surgeon’s tent to find it jammed with casualties, so many that they spilled out of it to lie everywhere around it. Some were appallingly still, others groaned, howled, cried out. When his stretcher bearers would have pushed all the wounded aside to get Caesar immediate attention, Octavian stopped them.

“No!” he gasped. “Put me down in turn! I will wait until the medics consider my wound the next to be treated.”

And from that they could not budge him.

Someone bound the knee tightly to stanch the bleeding, then he lay and took his turn, the soldiers trying to touch him for good luck, those with the strength crawling to take his hand.

Which didn’t mean that when his turn came, he was palmed off with an assistant surgeon. The chief surgeon, Publius Cornelius, attended to his knee in person, while an underling began to pluck the splinters from his hands and forearms.

When the packing bandage was removed, Cornelius grunted. “A bad wound, Caesar,” he said, probing delicately. “You’ve broken the kneecap, which has splintered in places and come through the skin. Luckily none of the main blood tubes has been torn, but there is a lot of slow bleeding. I’m going to have to pick out the fragments—a painful business.”

“Pick away, Cornelius,” Octavian said with a grin, aware that every other occupant of the huge tent was watching, listening. “If I yell, sit on me.”

From where he got the fortitude to endure the next hour, he didn’t know; as Cornelius worked on the knee he kept himself occupied in talking to the other wounded, joking with them, making nothing of his own plight. In fact, were it not for the agony, the entire experience was fascinating. How many commanders ever come into the surgeon’s tent to see for themselves what war can do? he wondered. What I have seen today is yet one more reason why, when I am undisputed First Man in Rome, I will pile Pelion on top of Ossa to avoid war for the sake of war, war in order to secure a triumph after a governorship is over. My legions will garrison, not invade. They will only fight when there is no other alternative. These men are brave beyond imagining, and do not deserve to suffer needlessly. My plan to take Metulum was a poor one, I did not count upon the enemy’s having sufficient intelligence to do what they did. And that makes me a fool. But a lucky fool. Because I have been badly wounded as a consequence of my bungle, the soldiers will not hold my bungle against me.

“You’ll have to call it a day and return to Rome,” Agrippa said after Metulum capitulated.

The gangways had been rebuilt upon a stouter framework and guards posted to make sure no Metulan miners repeated their work; the very fact that Caesar had been severely wounded spurred the men to get inside Metulum. Which burned to the ground after some of its inhabitants panicked. No spoils, no captives to be sold into slavery.

“I fear you’re right,” Octavian managed; the pain was worse than immediately after his injury. He plucked at his blankets, eyes sunk in their orbits. “You’ll have to carry on without me, Agrippa.” He laughed wryly. “No impediment to success, I know! In fact, you’ll do better.”

“Don’t blame yourself, Caesar, please.” Agrippa frowned. “Cornelius tells me that the knee looks inflamed, and asked me to persuade you to take some syrup of poppies to ease your pain.”

“When I am out of the district, perhaps, but until then, I cannot. Syrup of poppies isn’t available for a humble legionary, and some of them are in more agony than I am.” Octavian grimaced, shifted on his camp bed. “If I am to scotch Philippi, I must keep up appearances.”

“As long as that means you survive, Caesar.”

“Oh, I will survive!”

It took five

nundinae

to transport a litter-bound Octavian to Tergeste, and another three to get him to Rome via Ancona. An infection set in that saw him traverse the Apennines in delirium, but the assistant surgeon who had traveled with him lanced the abscess that had formed, and by the time he was carried into his own house, he was feeling better.

Livia Drusilla covered him in tears and kisses, then told him that she would sleep elsewhere until he was fully out of danger.

“No,” he said strongly, “no! All that has sustained me is the thought of lying next to you in our own bed.”

As delighted as she was worried, Livia Drusilla consented to share his bed provided that a curved cane roof was placed over the injured knee.