Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (33 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

But on April 12, nine days after the ransom was paid, the first bill surfaced. In a bakery in Greenwich, Connecticut, “a smartly-dressed middle-aged woman” used it to pay for her purchases. When she saw that the shopkeeper recognized the bill, she snatched it back and walked out to her green chauffeur-driven sedan.

80

No one thought to record the license number.

By now, Condon’s name was all over the newspapers. Reporters rang his doorbell, tapped on his window, and trampled over his frontyard. Condon studiously tried to finesse the truth, hoping not to alienate the kidnappers, to protect himself, and to stay in the game. Speaking from his front porch, he said:

I had contacts with the kidnappers and have direct contacts with them still. I have never identified them nor said a word against them. I value my life as they value theirs, and I know my life would not be worth anything if I said anything against them. I would be the happiest man in the world if I could place the baby’s arms around his mother’s neck.

81

The press continued to hound him, camping at his door and badgering him for more information. Lindbergh was worried, communication was impossible. Blaming the kidnappers’ silence on the press, Anne and Charles issued a statement on April 15:

It is still of the utmost importance for us and our representatives to move about without being questioned and followed, and we are again requesting the complete cooperation of the press to that end.

82

Then another bill surfaced. In New York, David Isaacs, a retired clothing merchant, found that a twenty-dollar bill given to him was marked, and he turned it over to a Secret Service agent. He received it on April 6 from the East River Saving Bank, not long after the ransom was paid. Apparently the kidnappers had tried to dispose of some of the money before the banks were alerted.

83

And soon a pattern began to emerge: the notes were passing north and south along the East Side.

In a letter to Evangeline on April 18, Anne expressed her anger at the many rumors and unsubstantiated claims.

84

As if in response, Schwarzkopf issued an explanatory statement, and then shut down communication with the press. But, public interest gained new momentum. A constant stream of cars, thousands of them, passed along the road leading to the Lindbergh estate.

85

The only good news, Anne wrote, was her doctor’s assurance that her pregnancy was going well.

When Elisabeth came to Hopewell the following weekend, Anne managed to maintain an air of quiet stoicism. But, in truth, she was exhausted and didn’t know how much longer she could keep up her spirits.

86

Yet Elisabeth wrote to Connie Chilton, on April 22, that they had spent a lovely day exploring the woods, which were beginning to burst with bloom. Anne was magnificent, she wrote, praising her strength and fortitude. Never once did she appear to break down. And yet, Elisabeth observed that Anne had withdrawn from the horror of the event, blocking out the chaos around her. The newspapers, the reporters, and the police meant nothing to Anne. What did they have to do with Charlie?

87

Betty Morrow, however, was terrified. She seemed to have absorbed all the tension and fear. She wondered how much Anne could endure before endangering herself or her pregnancy. Like Betty’s saintlike mother, who had tended her twin sister, she spent all her time making sure that Anne was sleeping and eating well.

Life at Hopewell adopted a predictable pattern. Police activity, which was distant from the Lindberghs’ living quarters, grew less as expectations diminished. Even Condon was beginning to doubt that the baby would be found alive.

On April 23, fifty-two days after the kidnapping and three weeks after the payment of the ransom, Condon stopped running his ad in the

Bronx Home News

. The press concluded that the Lindbergh baby hunt was “futile;” Charles thought otherwise. Unknown to the press, Charles had agreed to accompany John Curtis on a search along the Virginia coast for a ship called the

Mary B. Moss

, now said to be the one housing his baby.

With a detailed description of the kidnappers as well as an explanation for their motives and movement, Curtis had finally convinced Lindbergh that his story was true. Schwarzkopf, who thought Curtis’s story to be a hoax, acknowledged that he had produced nothing, so once again he permitted Charles to have his way. But after a week at sea in stormy waters off the Virginia coast, Lindbergh and Curtis had had no sight of the

Mary B. Moss

. Lindbergh, exhausted, irritable, and furious at the press, somehow continued to believe that Curtis held out the only hope. By the first week in May, the press, having got word of Lindbergh’s whereabouts, plastered the coastline with ships. Curtis said it was time to move to a sturdier boat. The gang was probably moving to rougher waters up north for the rendezvous. Lindbergh was elated. This was surely the last stop. The baby, Curtis told him, was in the waters near Cape May, off the coast of New Jersey.

After weeks of waiting for Charles to return, Anne was now convinced that Curtis was a liar. No one believed his story—no one but Charles.

88

Anne and the police tried to dissuade him, but Charles insisted on sailing Curtis’s yacht, the

Cachelot

.

He set sail for Cape May on May 9. For three days he and Curtis sailed aimlessly in search of the

Mary B

. while Curtis spun stories of gang dissension and fragmentation. Though Lindbergh continued to take Curtis’s word, Anne had had enough. Tired of the talk and deception, she turned inward, trying to find consolation in her own thoughts and memories. After three months of silence, Anne began to write in her diary. On May 11, 1932, she wrote that the kidnapping had an “eternal quality.” She was condemned to see her boy “lifted out of his crib forever and ever, like Dante’s hell.”

89

Anne didn’t want to possess the baby; she wanted only to see him, to comfort him, to touch his beauty. She didn’t want what she couldn’t have; she wanted only that life would make sense.

Schwarzkopf tried to encourage her, and Anne was grateful, but she knew that he could not sway Charles. Commander, interrogator, and now family friend, Schwarzkopf was as frustrated as she. He had tried to keep in touch with Lindbergh on the yacht, but the storms at sea had

prevented communication. On May 12, however, there was a message that demanded Lindbergh’s immediate attention.

Once again defeated by storms, Curtis and Lindbergh had dropped anchor along the New Jersey coast. Curtis went ashore, telling Lindbergh he needed to talk to the kidnappers through his gang contacts. Lindbergh, helpless, did some menial chores on the ship to keep himself busy. On reaching shore, Curtis received the coded message from Schwarzkopf and, unable to decipher its meaning, called police headquarters in New York. Immediately, two detectives set out for Cape May.

While the news was hitting the wires and the evening papers, Schwarzkopf drove to the Lindbergh estate, where he spoke briefly with Mrs. Morrow. Together they walked up the center stairs to Anne, sitting in her bedroom and reading in the light of a dreary afternoon. Schwarzkopf told her that the baby’s decomposed body had been found an hour earlier, buried beneath dirt and leaves in the woodlands of Melrose, no more than five miles southeast of the Lindbergh home.

Rocking her daughter in her arms, Betty said the words as gently as she could: “Anne, the baby is with Daddy.”

90

Ascent

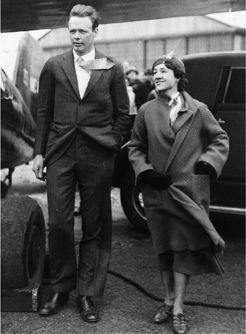

Anne and Charles, after the kidnapping, fall 1932. (Sygma)

Plunge deep

Into the sky

O wing

Of the Soul

.Reach

Past the last pinnacle

of speech

Into the vast

Inarticulate face

of Silence

.—

ANNE MORROW LINDBERGH

1

AY

12, 1932, H

OPEWELL

, N

EW

J

ERSEY

S

tanding on the deck of Curtis’s

Cachelot

as it sailed north toward Cape May, defying all that seemed logical, Charles had never been more certain he would bring the baby home to Anne. Each day he had cabled her from the ship, buoying her hope, raising her expectations. And Anne had so much wanted to believe that this time Curtis’s story would be true. Even when she could no longer bear it, even when Curtis seemed to her just another melting “face,” she took hope because Charles believed him. Now that she knew the baby was dead, she had to summon enough strength for both of them. She had to think clearly and stay in control.

Within half an hour of learning of her baby’s death, Anne wrote once again to her mother-in-law. Her cool words and measured phrases turned the death of her blue-eyed lamb with the golden curls she loved to touch into an event she had to process and document. He was no longer “Charlie,” but merely a body identified by its

teeth and hair, dressed in a nightsuit and killed in an instant

2

by a savage stranger indifferent to her pain.

Anne blamed the baby’s death on the press, as if it had conspired with the kidnappers. But on the discovery of the baby’s body, the reporters turned their rancor, only days before directed toward the Lindberghs, toward the perpetrators of the crime. The media saw the kidnapping as a desecration of America, a crime against the hero and his state. The editors of the

New York Times

wrote that those who committed this “most merciless, perfidious, and despicable of deeds” against “the ‘Little Friend of all the World’” were less than human, not even welcomed “by fallen angels in hell.” Their crime, wrote the

Times

, was more hideous than Pharaoh’s, more fiendish than Herod’s, because, while theirs were intended to defend of the state, the killing of the Lindbergh baby was a gratuitous act.

3

As if in agreement, Schwarzkopf pulled out all the stops. Furnished with descriptions from Curtis, he authorized a land, sea, and air search from the New Jersey shore to Cape Cod. Not to be outdone by Curtis, Condon declared he knew exactly to whom he paid the ransom and could pick the man “out of a thousand.”

Anne, frankly, didn’t care. On May 16, she wrote in her diary, “Justice does not need my emotions.”

4

The next day, however, Anne’s emotions took over. And once her tears started, they would not stop. It was the physical loss that overwhelmed her—the knowledge that she would never see or touch her child again. Memories flooded back, and moment by moment she had to barter for self-control. Anne’s tears permitted her to feel the cruelty of her baby’s death.

5

And yet her thoughts echoed the official police report: “death due to external violence to the head.” “External violence”—someone, something so depraved and hideous, it could not be human.

Anne walked the Hopewell estate, now in the full bloom of spring, with her mother and Elisabeth. When she saw the graceful blossoms of dogwood “like white stars cascading … upturned to the sun,” she couldn’t bear the pain.

6

Later, her feelings were captured in a poem, “Dogwood.” Expressing the recognition of nature’s indifference to human death was to become the purpose, the justification of her art, moving from her diaries and letters to her poems, essays, and books. Like Rilke, Anne began to hear “demon voices” condemning her blindness and neglect. She had failed to protect Charlie, to hear the ordinary sounds and signs that might have warned her of his death. Now everything around her was seared, and she was determined to transmit the sting of her senses. In her poem “No Angels,” she asks, as Rilke did in

Duino Elegies

, a faceless but intimate listener why she had not heard the message: