Andromeda Klein (30 page)

Authors: Frank Portman

Andromeda’s concern was different. She knew she wouldn’t be able to avoid laying out some cards and faking a lottery-numbers reading. Yet she was determined not to disarrange the order of the cards till she had had a chance to document and study them. For it was likely that Daisy had been the one who had constructed the hiding space in

Sexual Behavior in the Human Female

and had placed the cards in it; and it was possible that she had done this without shuffling them (because there’s no reason to shuffle at the end of a reading). Thus, it was just conceivable that Daisy’s last spread before placing the cards in the book, whenever that had been, was possibly preserved and might be reconstructed.

Huggy, if you really can help me remember things, now would be the time, Andromeda thought pointedly, imagining a future Huggy-summoning operation in which the HGA would dictate the cards to her as It had done with the King of Sacramento’s numbers.

The response came almost instantly, all of a sudden, a powerful, vibrating voice discerned in the hum of the fluorescent lights, not distant but very present, so present that it was astonishing that no one else could hear it:

Don’t shuffle

, It said.

Cut the deck in half and deal from the top, and don’t use more than twenty-nine cards. Also, don’t get back in that car

.

The voice was gone.

Later on, she realized, of course, that that was exactly the way to ensure that the top and bottom ten cards of a seventy-eight-card deck would remain in their original order. And she was glad she trusted the voice. After a cursory lottery-number-generating operation she invented on the spot (reducing the number value of pairs of minor arcana cards, leaving out the court cards, and counting major arcana as single numbers), the top and bottom ten remained in the middle of the deck, separated by the Three of Swords.

The numbers for Saturday had already been drawn, so they played them for Wednesday on the lotto machine at the counter. If their numbers won the jackpot, and no one else did, they would split it four ways, and it was easy to calculate even without Huggy’s help: the cash value award would be around $2.8 million apiece.

“One more thing,” said Andromeda, feeling shameless, but also rather clever. “I have a bad feeling about the, uh, the Gimpala. Some of those cards were, mm, ominous. Severe numbers like threes and fives, and lots of wands, which are fire. You don’t want to mess with that kind of elemental imbalance. I don’t think we should drive it home. I mean, you can. But, you know, don’t die.” It probably wouldn’t have persuaded the highest tarot court in the land, but she said it quickly and with as much confidence as she could.

Whatever Rosalie would have said next was interrupted by the sudden piercing sound of sirens in the distance. There was no need to point out how weedgie that was.

“It’s like there’s a fire every night around here these days,” said Josh.

“Elemental imbalance,” said Andromeda.

“No kidding,” he said.

Josh laughed long and hard when Bethany explained how the Gimpala was stuck permanently in reverse, and said he’d drive them home and would take a look at the transmission in the morning. But he made Rosalie demonstrate her backing-up technique in getting the car to the garage, just because he wanted to see it. Even half drunk, Rosalie managed it expertly and at great speed. After that, Josh seemed a little more interested in her.

Although her house was closest, Rosalie arranged to be dropped off last. Bethany rolled her eyes at Rosalie as she got out of the car but smiled at Andromeda and lightly kissed the top of her head before trotting off. They left Andromeda by the corner, clutching her still-vibrating

Sexual Behavior in the Human Female

and feeling a warm feeling on top of her head and silently thanking, giving praise to, Huggy for making it all happen and enabling them all not to die.

“Wednesday,” said Josh as he rolled up his window. “Drugs and guns as far as the eye can see. And for me: hookers.”

Even if Rosalie ended up doing something she regretted, Andromeda felt, not dying before having the chance to consult Daisy’s Pixie deck was surely worth it.

xvi.

The first thing to do, Andromeda Klein was thinking, while waiting at the St. Steve spot down the hill for Byron the Emogeekian to pick her up to take her to church, was to set aside half a million dollars for each of the parents. She would have to have a lawyer draw up a contract so the mom couldn’t touch the dad’s share, because the mom would immediately take it all and spend it if she could. It would be satisfying to cut the mom out completely, but giving her five hundred thousand to squander might give the dad time to make a getaway with his. Den would get something too, in some kind of account that Mizmac could never touch. What was left would be used to buy back all the Sylvester Mouse books and to fund a private library that she would design herself, along the same lines as the International House of Bookcakes but far, far away from Clearview, near Mount Shasta or New York or somewhere like that. Scholars and magicians could visit it by appointment only after having proved their worthiness, via online questionnaire and personal interview. And she, the Mistress of the Library, would live in a tiny cylindrical room atop a tower that would rise behind the main structure, a room that would also serve as a temple and astronomical observatory and house her magical and scientific equipment.

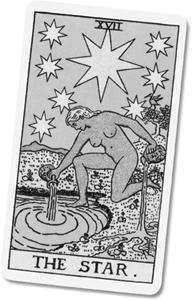

The top ten and the bottom ten cards in the Daisy deck hadn’t, when spread out in the Celtic Cross pattern, been particularly illuminating. It was impossible to know for certain what order they had been in, or even if they had been readings at all. As at the station, however, there had been a surfeit of Wands—rather remarkable, in fact, since the lottery oracle had included three Wands cards, and the remaining seven had all managed to turn up in one or the other of Daisy’s possible readings. But laying out the cards in the peace of her banished, consecrated room had been satisfyingly weedgie nonetheless. Daisy’s scent had filled the space as soon as Andromeda had opened

Sexual Response in the Human Female

, and she had felt an unmistakable tingly chill, particularly on the back of her hand, when she had touched the High Priestess, a card she had always associated with Daisy, rightly or wrongly. “Who’s here?” she had asked. And, as though in response, a rushing sound of the wind in the curtains had seemed to announce Dave, who approached her carrying Daisy’s old Little One in his mouth and dropped it in front of her. That was all the more impressive because Andromeda had left it in the Daisy bag and he had had to dig it out.

But it was much harder to read cards without notes scribbled on them. Redoing them would take a great deal of work, and she hated to sully the pristine Daisy deck at any rate. The lottery-funded library-temple in New York or Shasta would have an annotated tarot deck at each table, ready in case any patrons needed to use it to look something up, she decided. And perhaps she could have a limited number of annotated decks printed up for sale in the gift shop.

You’re not going to win that lottery

, said Huggy. It was hard to know where to direct the glare in response: somewhere inside her head, or her heart, or in another, unseen dimension occupying the same space, or perhaps floating above her. She was trying anyway when Byron arrived, leaning her shoulder in and looking down, and she must have looked weird.

“Why yummy muggy me?” he said, rolling down the window and leaning up to it as he opened the door. “The look of death,” he added.

(Mean-mugging

, stage-whispered Huggy in her head.

He’s referring to your impertinent countenance.)

“Shut up,” she said, and that went for both Huggy and Byron, though only he seemed hurt by it. Huggy was a help but made things difficult, too. Well, “the look of death” wasn’t the nicest thing to say. Andromeda had felt she looked unusually cute that morning in her own mirror, but that was with the lighting arranged to her advantage, and holding her head just right. No telling what havoc the cool morning light would bring …

“countenance.”

Now, that was what the dad would call a fifty-cent word (because when he was learning words fifty cents was this huge amount of money), and she chalked one up for Huggy and made a mental note of it for future use.

Andromeda only put effort into figuring out what people really meant to say when there was a chance she’d be interested in their opinions. Otherwise, she’d have spent nearly one hundred percent of her time in a guessing game. She doubted Byron would have much of interest to say on any subject. But pulling her hair and hood back from her ear and tilting her head was an unavoidable reflex.

“What? Oh, I was thinking about the lottery.”

Byron waited respectfully, as he always did, as though expecting some significant clarification or words of wisdom to follow. He waited till she was in the car and they were on the road before he said:

“So did you listen to it?”

It took Andromeda a moment and a little prod from Huggy to realize he was talking about the Choronzon CD he had given her. In fact, she had forgotten all about it. The idea of Cthulhu rock was a lot more interesting than the reality, which was horrible and hurt her ears and had little value that she could see. Just a growling man with a loud clatter in the background. She hadn’t made it through the first twenty seconds. It was funny, though, to imagine the dad in his studio recording stuff like that, saying “Okay, boys, ‘The Boundless Daemon Azothoth,’ from the top” in his Groucho voice.

“Oh yes,” she said. “Thanks. It was awful, but I liked it.”

He was silent, as though waiting for her to say more. “Oh, good,” he finally said, but he was acting mad. The mom did this all the time, so Andromeda knew what was expected and she followed up with some extravagant words of praise and thanks that would have sounded sarcastic to anyone other than the person they were directed at. Like the mom, Byron ate it up, and was all, or mostly, smiles again.

“I’m so glad you liked it,” he said, not letting the subject go.

Ye Gods

, said Huggy,

you’ve hooked up with a moron boy

, not realizing, perhaps, that hooking up and going to church were, in the twenty-first century, often two rather different things. But Andromeda said, “Especially that one song,” which finally seemed to put the subject away and seemed to make him smile way too hard.

She caught her reflection in a gutter puddle on the way up to the church steps, and wished she hadn’t. It was a bad angle. She curled her hair under a little with her hand and pulled her hood a little farther around her face.

“Okay, Blessed Mary Ever Virgin,” said Byron, trying to be funny.

The emogeekian had made an effort and had cleaned up pretty nice. Leather shoes, a kind of suit jacket (no tie, though), and he had shaved off the scraggly little beard. He was still too short, though the shoes made him a little taller at least. Was this how Catholic boys always dressed to go to church when they were trying to impress weedgie girls and persuade them to teach them magic? Maybe so, but he had also pretty closely adhered to her instructions, if taking note of her complaints about his appearance and correcting them as best he could counted as following instructions.

Of course it does

, said Huggy.

That’s what

instructions

means

. Andromeda had to admit, it was nice to be listened to.

“I like your cat collar,” he said.

“It’s a choker,” she corrected, but found herself liking that he noticed it and also liked the word

choker

, which she didn’t often have occasion to say aloud. Could he possibly really have a male tramp stamp like Rosalie had said?

St. Brendan’s was tiny, far smaller than Andromeda had expected it to be, smaller even than the main churchlike building of the International House of Bookcakes. In spite of herself, and to her surprise, she realized she was rather frightened at the prospect of actually attending a service, but the church building was far less scary and Transylvanian than she had pictured it. It looked like a school from the outside.

“Where would the anchoress go?” she wondered aloud to herself, but Byron heard, because he said: “Where would the what what?”

An anchoress, she explained patiently, as though it were common knowledge, even though she had only just looked it up herself, was a woman who lived in a small, sealed room inside of or attached to a medieval church. There was one window through which she could observe the church services, and another on the outside so that villagers could converse with and pass gifts and food to her. Her job was to meditate and pray, a very important role in the Middle Ages. The boy version was called an anchorite, but anchoresses were more common.

“I don’t think we have those anymore,” said Byron dryly.

Of course, Andromeda had known there wouldn’t be an actual anchoress at the suburban church in twenty-first-century California. She had just been trying to picture where the anchoress’s cell would have been and what it would have looked like, had this been a medieval church. Because she could see why the King of Sacramento had referred to her as an anchoress: the description on the Internet reminded her very much of her box. She often felt rather anchoress-esque, when she thought about it, shy and self-contained and voluntarily confined in a small space, exploring inner worlds while remaining in a stationary trance. I’d have made a good one, she thought as they headed up the steps and slipped through the main doors.

The vestibule was deserted. Miniature statues of saints, mostly ladies, one bearded non-Jesus man, and a little child in a crown and a dress stood against the walls surrounded by what appeared at first glance to be tiny, flickering candles but turned out on closer inspection to be tiny electric lights. Byron had a point: all the female saints did look like they were wearing hoodies in a way, and they were all thin and frail-looking, too. Maybe their hair underneath was just as awful as Andromeda’s. In fact, that was pretty much guaranteed, pre-blow-dryer era.

“These all used to be bacon gods,” she whispered, trying to explain how the early Christian church had replaced local deities with its own saints in popular worship.

They’re still pagan gods!

stage-whispered Huggy. And of course It was right: changing their names changed little; that was just something humans did on account of their own vanity. A good magician, of course, would know to learn all their names if he wanted to make proper use of them.

Andromeda had expected these incidental shrines, and had been prepared to give this mini-lecture on their origins. She had researched it and even practiced it in the bath that day. Half-whispered, half-thought, it had sounded impressive and weedgie. But as usual, out in the air, the words—from the yet-to-be-written volume XX of

Liber K—

came out garbled and nonsensical, and Byron just stared at her.

“No, I’m pretty sure this has always been the mother-o-saurus,” said Byron, pointing to the sign that said

MOTHER OF SORROWS

.

She couldn’t tell which he had meant to say, so Andromeda half smiled in case it was a joke, then added: “Well, the mother-o-saurus looks a lot like Isis.” She pulled

Sexual Response in the Human Female

from her bag, found the High Priestess, and held it up against the picture of the mother-o-saurus, whose halo and rays looked, maybe, a

little

like the High Priestess’s headdress (though not quite as much as Andromeda had expected it to). “So this crown is the crown of Hathor, the sun with cow horns around it. And Isis was a virgin and the mother of Horus. She’s also the Statue of Liberty, too.” And Wonder Woman. The crowns weren’t looking similar enough to make her point the way she thought they would, but she knew she was right. It was in lots of books. “She was called the Popess in the Middle Ages,” she added lamely. An anchoress with a special hat, she thought, remembering the King of Sacramento.

Byron said “Holy shit” to indicate that he was impressed, but it didn’t seem like his heart was in it. She would have to consult Mrs. John King van Rensselaer so she could describe it better, how the emblems of ancient cults got updated and passed down to future civilizations over and over, how gods and goddesses got recycled.

The mother-o-saurus in the picture had a heart stabbed with swords floating above her chest, just like the King of Sacramento.

Not just like

, said Huggy, surging in.

Do I have to count them for you?

There were seven little swords puncturing the mother-o-saurus’s heart, rather than the three in Pixie’s Three of Swords card that the King of Sacramento had had on his chest beneath his robe. The Seven of Swords is … Andromeda couldn’t remember the Golden Dawn motto.

Futility

, said Huggy.

You of all people should know: it’s futility

.

“Futility, of course,” said Andromeda, loudly enough that Byron shot her an “Are you feeling all right?” look.