And the Band Played On (33 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

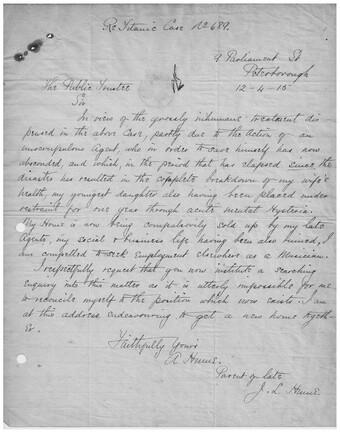

I respectfully request that you now institute a searching enquiry into this matter as it is utterly impossible for me to reconcile myself to the position which now exists.

I am at this address endeavouring to get a new home together

Faithfully yours,

A Hume,

Parent of late J. L. Hume.

Hume makes no mention in the letter of his attempts to claim compensation from the White Star Line for the two valuable violins he alleged Jock took with him on the

Titanic

. There is no record of a reply from the Public Trustee. The tone and content of Andrew’s letter suggests that he was desperate, almost to the point of being suicidal. Yet, as he was soon to demonstrate, he was very far from being down and out. Andrew was already well on the way to reinventing himself.

The Humes stayed in Peterborough until the end of the First World War, Andrew making violins and finishing them, and also buying and selling them. They then moved briefly to Bedford before settling in London, where Andrew set up shop at 167 Brixton Road. From here he advertised in

The Strad

:

a few fine old Italian violins and best modern maker’s specimens for sale, cheap. Also good bows, violas,

etc.

Highest-class repairs and refitting executed to order.

Brixton did not suit the Humes and within a few months he took a lease on a more central property in Great Portland Street on the other side of Oxford Street from Soho, where most of the quality shops selling musical instruments were, and still are, to be found. Here, away from the scandals, the tragedies and the memories of Dumfries, Andrew Hume regained his old confidence and Andrew Jnr, now aged nineteen, launched himself in his own career as a musician, forming a quartet called Andy and the Boys.

In 1920 Hume acquired a fine violin by the Milanese violin maker Leandro Bisiach. It seems to have been made for Hume as Bisiach has signed the violin and apparently added Andrew’s name, handwritten, to the label inside. How Hume came by it is one of those mysteries that provide endless debate in the elegant and subtle world of stringed instruments. After Hume’s death it found its way to the collection of the famous violinist Howard Davis, leader for 35 years of the Alberni Quartet and a teacher at the Royal Academy of Music. For a period, it was Davis’s own preferred instrument. It was sold in 1984 for £6,000 and is still in use today in the hands of a gifted violinist with the Welsh National Opera.

Around this time, Hume also seems to have acquired a Guadagnini. It featured in one of Andrew’s first advertisements for his new business at 34 Great Portland Street near Oxford Circus, where he and Alice lived above the shop. It appeared in

The Strad

in 1921:

FINE VIOLINS THIS MONTH BY

PRESSENDA, 1830; ROCCA, 1855;

L. GUADAGNINI, CERUTI

Also best Moderns, Bows, Strings, etc

Old instruments bought or exchanged

If your old instrument is not giving you

its usual satisfaction

send it on for rebarring or readjustment to:-

HUME, 34 Great Portland Street, W.1

By the following year, Andrew Hume was taking a large advertisement the full width of the page in

The Strad

. He was now describing himself as a ‘Violin Expert, Maker & Repairer’. The instruments offered for sale included ‘One baby Grand Piano as supplied to the Court of Italy’, a Stradivari from the ‘Heroz Coburg-Gotha collection’ [sic] and ‘a few of my own specials’.

A. Hume – significantly, Andrew never used his Christian name – became a prodigious correspondent on

The Strad

’s letters pages, contributing to debates about varnish and glues, and shamelessly exploiting any opportunity to promote his own instruments and expertise. In 1921 he wrote:

Since the June issue of your esteemed paper I have had a great many visitors to examine the specimens I have on hand at present, all parties making practically the same remark, viz., that they have never seen any varnish so perfect and beautiful, the wood and workmanship being equally so.

Hume also entered music competitions, sharing a twenty-guinea prize donated by the philanthropist Walter Wilson Cobbett in a competition organised by the Royal College of Music and winning a gold medal at the British Empire Wembley Exhibition of 1924–25. The Wembley exhibition seems to have been a turning point in Andrew’s new life. It was opened by King George V, who made the first ever broadcast by a British monarch and further marked the occasion by sending a telegram to himself around the world and back (via every far-flung outpost of the British Empire, of course); it took one minute and twenty seconds. Sir Edward Elgar brought ‘a choir of 10,000 voices’ to the opening ceremony. Andrew seized the opportunity offered by the huge public interest in the exhibition and took a stand – number v.917 in the ‘Palace of Industry’ – personally welcoming visitors. His advertisement in the April 1924 issue of

The Strad

made what was to be an irresistible offer to readers:

Empire Exhibition Wembley

Stand v.917 Palace of Industries [sic]

Should your violin NOT be giving you all the pleasure you desire when in use, take or send it to the above stand from 11am till 4pm any day and have my personal comment upon it. The following is one of many recently expressed opinions on the results of this course:

Dear Sir, My lucky star was in the ascendant when I brought my fiddle to you. You are a magician. The tonal improvement in it since can only be described as magical, the former ‘rawness’ has vanished and left a pure and clear singing tone behind. If the cost to me had been many times what it was, I would still be your debtor.

With many thanks, Yours truly, J.G.A.

Having relaunched his career through the exhibition, Andrew spent the next two years using the exhibition to promote himself relentlessly in a series of advertisements in

The Strad

.

The Hume Violin, Viola, Cello

Highest Award, London, 1918 and

B.E. Exhibition 1924–25

Pronounced by Messrs Strockoff, Thibaud

to be quite unsurpassable on all points.

A recent purchaser writes:

There is a charm, delicacy and refinement about it, as well as power and a wonderful reserve that is very rare, the more I play upon it the better I like it and I am enjoying my music more now than in the past. I simply can’t let it alone.

Andrew’s pioneering use of celebrity endorsements – Leo Strockoff and Jacques Thibaud were two of the greatest virtuoso violinists of their generation – would not stop there. From his stand at the exhibition Andrew had launched a gadget for anchoring cellos firmly to the floor. This ‘perfect cello and bass fixer’ cost 4s 6d and came with an endorsement from Pablo Casals: ‘Very simple and most efficient. Sincere congratulations – Pablo Casals.’

Given Andrew’s track record for deceit, it seems highly unlikely that Strockoff, Thibaud or Casals had said what Andrew claimed. However, modesty and caution were not among Hume’s characteristics and now he was back in his stride, boasting and selling:

I have ten recipes of Old Italian Varnishes of dates 1550, 1564 and 1745. I made the varnish used on this specimen (violin) in 1907. I consider it to be the very purest and finest preservative to be seen today . . .

I have also a number of FINE OLD MASTER

VIOLINS, VIOLAS and CELLOS for disposal.

It had taken Andrew Hume ten years to rebuild his life from the wreckage he had left behind in Dumfries. Once again he was a man of position, with a prosperous business and a great gift – this time for making and restoring violins, rather than playing them. Yet despite the veneer of success and the confidence he exuded, scandal and suspicions continued to follow him, centring around instruments that Hume referred to modestly as ‘one of my own specials’. They carried the initials A. H. but no one – including Andrew Hume himself – knew whether the ‘A’ stood for Alexander or Andrew. He signed all letters ‘A. Hume’ and called his business ‘A. Hume’.

Andrew’s great skill in obtaining and applying old Italian varnishes lay behind many of the doubts surrounding instruments he made or sold. He had a reputation in the trade for selling violins that were not always what he claimed they were. Mistakes were sometimes found in certificates of authenticity. There were disputes over provenance. ‘Let’s just say that people in the trade learned to be very careful when they were offered an instrument by Andrew Hume,’ says David Rattray, the distinguished Custodian of Instruments at the Royal Academy of Music and author of several books on the violin:

Early in March 1934 Andrew Hume sold his last instrument, a violin by Giovanni Guadagnini which he had advertised for sale in that month’s

The Strad

, a similar instrument to the one that Jock had supposedly taken with him on the

Titanic

. On 24 March Andrew collapsed after suffering a cerebral haemorrhage in his workshop in Great Portland Street. He was taken to the Charing Cross Hospital, where he died next day. He was sixty-nine. After the funeral, which none of his children attended, Alice returned to Scotland, but not to Dumfries. She died in Edinburgh on 11 April 1939, aged seventy-four.

The Strad

had already gone to press and the month after Andrew’s death it published his last classified advertisement:

Specially Fine Violins. No cracks. Chappuy, £8; Mezzin, £6; Degani, Bausch and others. Silver plated quick change to A flat Trumpet, low

pitch and unused. A and B flat Clarionets,

Albert and Boehm.

A. Hume, 34 Gt Portland Street, W.1.

It was not his only epitaph. The following month,

The Strad

published a short obituary, which began: