And the Band Played On (16 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

On Saturday 4 May thirty-three more unidentified bodies lying at the Mayflower Rink were sent to Fairview for burial. It seems likely that Jock was among these but the burial certificate leaves room for uncertainty as, six days later, on 10 May, a further thirty-three bodies were interred at Fairview, some of them having been brought back to Halifax by the

Minia

which recovered seventeen bodies, burying two at sea.

A memorial service for the dead was held at All Saints Cathedral on Sunday 5 May. Principal Clarence McKinnon paid tribute to the ‘unidentified . . . whose graves would be kept forever green’. He said, ‘They shall rest quietly in our midst under the murmuring pines and hemlocks but their story shall be told to our children and to our children’s children.’

Among the congregation was Captain Larnder and most of his crew. There had been little time for any of them to rest since their return to Halifax on 30 April. The day after unloading their cargo of corpses they had been ordered to prepare for their next voyage. Larnder’s log for Wednesday 1 May, headed ‘In Port’, described that day’s activities:

Paid off crew

Checked life belts

Shore gang began coaling ship

Carpenter repaired deck damage

Filling fresh water tanks

When the arrangements for the memorial service became known Larnder asked his employers, the Commercial Cable Company, if the

Mackay-Bennett

could delay sailing so that he and his men could attend the service. Permission was given and early on Monday 6th, the morning after the service, the

Mackay-Bennett

set sail again. Its three tanks, which had served as an ice mortuary, now held huge drums of cable. This time, Larnder’s mission was one that would give him pleasure, one that he understood and one for which he had been trained, though no less dangerous. They were to find and repair a break in the world’s longest undersea cable, connecting the 3,173 nautical miles between Brest and St Pierre, one of two French islands just off the Burin Peninsula off the south-west coast of Newfoundland. The cable had been laid in 1898 but later extensions took it on to Cape Cod and New York, increasing its importance and value as a fast telegraphic link between Europe and the USA. Larnder would be pleased to know that one hundred years later, the world wide web depended on a similar cable made of fibre optic connecting the two continents.

As they passed George’s Island, Larnder started a new page in the log. He headed it: ‘Brest–St Pierre’ and added for good measure underneath, ‘On to Cape Cod then New York’. A storm lay ahead but for the first time in three weeks Captain Frederick Larnder felt in control of his life again.

10

Mutiny on the

Olympic

4 May, Southampton

As the corpses of seamen were being carried off the

Mackay-Bennett

, fifty-four crew members on the

Titanic

’s sister ship,

Olympic

, were appearing in court in Southampton charged with mutiny. The episode has to be one of the most shameful and ill-judged prosecutions ever to come before a British court of law and, if it were not so shocking, it would be pure slapstick, involving as it does a captain called Herbert Haddock.

The

Olympic

, under the command of Captain Haddock, had been due to sail from Southampton to New York at noon on 24 April 1912. Like the

Titanic

, the

Olympic

had been built with an insufficient number of lifeboats for the passengers and crew and in the week following the

Titanic

disaster, the White Star Line scrabbled around to find more lifeboats before the

Olympic

put to sea. Harland & Wolff, the Belfast firm that had built both liners, were unable to supply wooden lifeboats in time so the White Star Line borrowed forty collapsible boats taken from troopships in Portsmouth harbour and loaded them on board the

Olympic

.

Southampton was still reeling from the death of 500 of its fathers and sons on the

Titanic

and, understandably, the crew of the

Olympic

who had lost family members and friends took more than a passing interest in the condition of the collapsible boats that their lives might depend upon. After examining them they decided the boats were rotten, unseaworthy and, for the most part, unfit for purpose. With only three exceptions, the entire crew of firemen, greasers and trimmers stopped work, collected their kit and left the ship singing, ‘We’re All Going The Same Way Home’, accompanied by a tin whistle band led by a self-appointed conductor.

With passengers already boarding the ship, the situation was not looking good for the White Star Line – and that was before the intervention of their Southampton manager, the undiplomatic Mr Curry, who told the men that their refusal to obey orders was ‘rank mutiny’ and that Captain Haddock could order the police to arrest them for desertion. An impromptu meeting of the strikers was held on the quayside. The secretary of the Seafarers’ Union, Mr Cannon, told the men that he did not wish to influence their decision and would be guided by their vote. ‘Not a single man voted to rejoin the ship,’ wrote a reporter from

the New York Times

who had watched the situation develop with interest as more than half of the

Olympic

’s passengers were American. Mr Cannon told the

Times

reporter: ‘The men inspected the boats when they were mustered this morning and found many of them in a rotten condition. One man is alleged to have put his hand through the canvas of one boat. All the boats are from six to ten years old, and when the men tried to open them they could not do so.’

The White Star Line began a frantic hunt for substitute firemen and trimmers, having apparently forgotten that it had drowned virtually a whole ship’s crew from the town two weeks earlier. Unable to find any living or willing hands in Southampton, it switched its search and managed to recruit 100 men in Portsmouth, bringing 150 more by special train from Liverpool and Sheffield. While the search for blacklegs was going on, the

Olympic

lay at anchor in the Solent, appropriately off Spithead, the scene of a successful Royal Navy mutiny in 1797. By this time, several of the

Olympic

’s 1,400 passengers were considering mutiny themselves, annoyed about going nowhere for two days and increasingly concerned about their own safety. The White Star Line’s attempts to amuse them by distributing kites to fly on deck was not a success.

At a meeting of the First Class passengers in the

Olympic

’s smoking room, the Duke of Sutherland decided that the crisis required more leadership than Captain Haddock was providing. Puffing away at a large Cuban cigar, the Duke asked for? ‘volunteer stokers’, who would work in shifts to get the ship to Queenstown where the captain might be able to raise a more amenable Irish crew. Surprisingly, seventeen First Class passengers offered their services, including an American businessman Ralph A. Sweet who accompanied Sutherland to put their plan to Captain Haddock. ‘He thanked us very nicely,’ Sweet said later. ‘I thought he was going to put us to work right away but he told us that he would not call on our services.’

On the night of 25 April, the substitute firemen and trimmers, having arrived in Southampton, were taken out to the

Olympic

by tugboat. Their arrival did not go down at all well with the fifty-four firemen and stokers remaining on the ship, who objected to the newcomers on the grounds that they were not union members and were unqualified to take the liner across the Atlantic. As soon as the relief crew started up the ladder to board the

Olympic

, they were passed on the way down by the fifty-four seamen, who demanded that the tug took them back to shore.

The Royal Navy now became involved in the dispute. Captain Haddock signalled for assistance by lamp to the cruiser

Cochrane

, whose captain, William Goodenough, boarded the tug to warn the men they were guilty of mutiny and liable to heavy punishment. The men still refused to return to the

Olympic

. The tugboat returned with the men on board to Southampton, where it was met by police who arrested them for ‘unlawfully disobeying the commands of the master of the ship’.

The White Star Line cancelled

Olympic

’s trip and refunded the passengers’ money, some of the passengers

‘complaining bitterly of the actions of the sailors declaring they would try to get back the cheques given in aid of the

Titanic

disaster fund’, according to White Star Line managers. The company then telegraphed the Postmaster General (the

Olympic

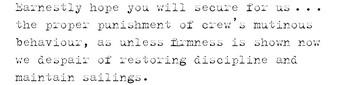

being a Royal Mail ship) as follows:

The ‘mutineers’ appeared before magistrates at Southampton that morning. At first they were made to stand in two rows facing the magistrates but they were then provided with seats. Mr C. Hiscock ‘appeared for the White Star Line’. He explained that the men were charged under the Merchant Shipping Act, which provided that if any seaman was guilty of wilful disobedience he was liable to be imprisoned for a period not exceeding four weeks. The court heard that of the 200 men taken on board to break the strike, only three were able to show they had ever been to sea. The men were remanded until 30 April, when they appeared again before the magistrates and were remanded. The case received very little coverage, eclipsed as it was by the simultaneous arrival in Britain that day of many of the

Titanic

survivors and the arrival in Halifax of the

Mackay-Bennett

with the dead, including Jock.

On 4 May, the fifty-four seamen were brought back to court, where they pleaded not guilty to mutiny. An ex-Naval officer and quartermaster, George Martell, was one of the witnesses for the defence. He said he was

‘thoroughly disgusted by the appearance of the men shipped in to take the place of the striking firemen . . . They were not the sort of shipmates for me,’ he said. They were ‘the scallywags of Portsmouth’.

The magistrates decided that the charges were proved but expressed the opinion that it would be ‘inexpedient’ to imprison or fine the men because of the circumstances which had arisen prior to their refusal to obey orders. The magistrates discharged them all and hoped they would return to duty, which indeed they did on 15 May, much cheered by the sight of new Harland & Wolff wooden lifeboats installed on the deck of the

Olympic

in time for its delayed voyage to New York.

‘No untoward incident marred the departure of the

Olympic

from Southampton,’ the

New York Times

reported the next day. ‘Most of the men concerned in the recent dispute rejoined the ship.’ The newspaper added that the leading fireman on the

Olympic

as it sailed to New York was a man called Barret, who knew a thing or two about lifeboats having just spent a night in one. One of the few crew members to survive the Titanic, Barret had just returned from New York having arrived there on the

Carpathia

with the other survivors. Before boarding the

Olympic

he was invited to tea by the Wreck Commissioner, who was ‘eager to hear his vivid story of the engineers’ experience after the collision with the iceberg’.

11

Titanic

’s Bandmaster Honoured

18 May, Colne, Lancashire

Unlike my grandfather Jock who had nothing to indicate who he was when his body was recovered by the

Mackay-Bennett

, Wallace Hartley, the bandmaster, was quickly identified. His violin case was still strapped to his chest; his initials, WHH, were on a gold fountain pen and on a silver matchbox found in his pockets; he carried several letters; and there was a telegram addressed to ‘Wallace Hotley, Bandmaster Titanic.’