Ancient Iraq (25 page)

CHAPTER 13

No matter how fascinating the ever-changing spectacle of political and economic situations, there are times which call for a pause; there are periods so richly documented that the historian feels compelled to leave aside monarchs and dynasties, kingdoms and empires, wars and diplomacy, and to study the society in a static condition as it were. How did people live? What did they do in everyday life? These are questions which come naturally to mind and deserve an answer.

1

In Mesopotamia the days of Hammurabi – or, more exactly, the century which begins sixty years before his reign (1850 – 1750

B.C

. in round figures) – is one of these periods. Here our sources, both archaeological and literary, are particularly copious. It is true that we know very little about the capital cities of southern Iraq: Isin and Larsa have just begun to yield their secrets, and eighteen years of excavations at Babylon have barely scratched the surface of the huge site, the height of the water-table having prevented the German archaeologists from digging much below the Neo-Babylonian level (609 – 539

B.C

.). In the small area where deep soundings were possible only a few tablets and fragments of walls pertaining to the First Dynasty were found, some twelve metres below the surface. But on other sites other archaeologists have been more fortunate. The monuments they have unearthed – the royal palace of Mari, the palace of the rulers at Tell Asmar, the temples and private houses of Ur, to mention only the most important – are perhaps not very numerous, but they are of outstanding quality. As regards written documents we are even better provided, for not only do we have the Code of Hammurabi, but his correspondence, the royal archives of Mari, Tell Shimshara and Tell al-Rimah,

2

and many legal, economic, administrative, religious

and scientific texts from Mari, Larsa, Sippar, Nippur, Ur, Tell Harmal and various other sites; in all, perhaps thirty or forty thousand tablets. Indeed, it can be said without exaggeration that Mesopotamia 1, 800 years before Christ is much better known to us than any European country a thousand years ago, and it would be in theory possible for historians to draw a fairly complete and detailed picture of the Mesopotamian society in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

B.C

. As this would go far beyond the boundaries of the present work, we shall limit ourselves to the sketching of the three main aspects of this society: the god in his temple, the king in his palace, the citizen in his house.

The God in his Temple

The temples – the ‘houses’ (

bitu

) of the gods as they were called – varied in size and layout. Some were small wayside chapels which were part of a block of houses and consisted of hardly more than an open courtyard with an altar and a pedestal for the divine statue,

3

others were larger detached or semi-detached buildings, comprising several courtyards and rooms,

4

and finally, there were the enormous temple-complexes of the greater gods, which often included several shrines for the minor deities of their household and retinue.

5

These temples no longer retained the admirable simplicity of the early Sumerian sanctuaries (see Chapter

4

). Throughout the ages they had increased in complexity to incorporate the numerous services of a strongly organized religious community. Moreover, their plan reflects a high degree of specialization in the performance of the cult, and it appears that a distinction was made between the parts of the temple open to the public and those reserved for the priests, or perhaps for certain categories of priests only. Whether the concept that the great gods could only be approached by degrees was developed by the Sumerians or introduced by the Semites is a much debated problem which cannot be discussed here.

All the main Mesopotamian temples had in common certain features.

6

They all comprised a large courtyard (

kisalmahhu

) surrounded by small rooms which served as lodgings, libraries and schools for the priests, offices, workshops, stores, cellars and stables. During the great feasts the statues of the gods brought from other temples were solemnly gathered in this courtyard, but on ordinary days it was open to all, and we must imagine it not as an empty and silent space, but as a compromise between a cloister and a market-place, full of noise and movement, crowded with people and animals, unceasingly crossed by the personnel of the temple, the merchants who did business with it and the men and women who brought offerings and asked for help and advice. Beyond the

kisalmahhu

was another courtyard, usually smaller, with an altar in its middle, and finally, the temple proper (

ashirtu

), the building to which none but the priests called

erib bîti

(‘those who enter the temple’) had access. The temple was divided by partitions into three rooms, one behind the other: vestibule, ante-

cella

and

cella

(holy of holies). The

cella

contained the statue of the god or goddess to whom the temple was dedicated. Usually made of wood covered with gold leaves, it stood on a pedestal in a niche cut in the back-wall of the

cella

. When all doors were open the statue could be seen shining faintly in the semi-darkness of the shrine from the small courtyard but not from the large one, as it was at a right angle with the temple doorway, or hidden behind a curtain, depending on the layout of the temple. Flower pots and incense burners were arranged at the god's feet, and low brick benches around the

cella

and ante-

cella

supported the statues of worshippers, together with royal steles and various

ex-votos

. A two-step altar, a table for the sacred meals, basins of lustral water, stands for insignia and dedicated weapons made up the rest of the temple furniture. Rare and expensive materials were used in the construction of the building: cedar beams supported its roof, and its doors were made of precious wood, often lined with copper or bronze sheets. Lions, bulls, griffins or genii made of stone, clay or wood guarded the entrances. At the corners of the

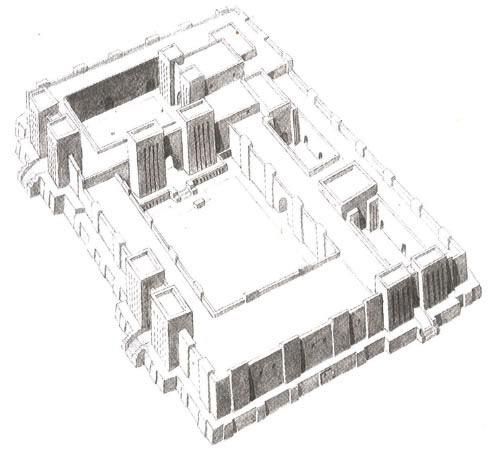

The temple of Ishtar-kititum at Ischâli (Diyala valley). First half of the second millennium

B.C.

Reconstruction by H. D. Hill. From H. Frankfort

, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, 1954.

temple precinct and buried under the pavement were brick boxes containing bronze or clay ‘nails’, royal inscriptions and the statuettes of the kings who had founded or restored the sanctuary. These ‘foundation deposits’ (

temenu

) authenticated the sacred ground, marked its limits and kept the netherworld demons at bay.

7

Every day throughout the year religious ceremonies were performed in the temple: the air vibrated with music,

8

hymns

and prayers; bread, cakes, honey, butter, fruit were laid on the god's table; libations of water, wine or beer were poured out into vases; blood flowed on the altar, and the smoke of roasting flesh mixed with the fumes of cedar-wood, cyprus-wood or incense filled the sanctuary. The main object of the cult was the service of the gods, the

dullu

. The gods were supposed to live a physical life and had daily to be washed, anointed, perfumed, dressed, attired and fed, the regular supply of food being ensured by ‘fixed offerings’ established once and for all by the king as supreme chief of the clergy, and by pious foundations. In addition, certain days of the month considered as sacred or propitious – the days when the moon appeared or disappeared, for instance – were devoted to special celebrations.

9

There were also occasional ceremonies of purification and consecration, and of course the great New Year Festival celebrated in some cities in the spring and the autumn. But the priests also served as intermediaries between men and gods. Better than anyone else they knew the proper way of approaching the great gods; on behalf of the sick, the sorrowful, the repentant sinner they would offer sacrifices, recite prayers and lamentations, sing hymns of grace and psalms of contrition; and as they alone could read into the mysterious future, there was no king nor commoner who, on frequent occasions, would not consult them and ask for an omen. For each of these acts of cult a strict and complicated ritual was laid down. Originally prayers and incantations were in Sumerian, but under the First Dynasty of Babylon the Akkadian language was allowed into the Temple, and we possess, for instance, a ‘Ritual for the Covering of the Temple Kettle-drum’, where it is said that a certain prayer should be whispered ‘through a reed tube’ in Sumerian into the right ear of a bull and in Akkadian into its left ear.

10

The chief administrator of the temple was the

shanga

, a high dignitary who, in the reign of Hammurabi, was appointed by the king himself. He was assisted by inspectors and scribes who registered all that entered or went out of the temple stores and commanded low-grade employees, such as guards, cleaners and

even barbers. The wheat and barley fields of the temple were run by

ishakku's

(Akkadian for

ensi

, which shows how low this once prestigious title had fallen), and were worked by farm hands and sometimes corvées which involved the entire population of the town or district.

A large number of priests were attached to the main temples.

11

Sons and grandsons of priests, they were brought up in the sanctuary and received a thorough education in the temple school, or

bît mummi

(literally ‘House of Knowledge’). At their head was the high-priest, or

enum

(Akkadian form of the Sumerian word

en

, ‘lord’) and the

urigallum

originally the guardian of the gates but now the main officiant. Among the specialized members of the clergy, the

mashmashshum

who recited incantations, the

pashîshum

who anointed the gods and laid their table, the

ramkum

who washed the statues of the gods, the

nishakum

who poured out libations and the

kâlum

who chanted incantations but also fulfilled some mysterious functions, were the most important. These priests were assisted by the sacrificer (

nash patri

, ‘sword bearer’), as well as by singers and musicians. Although he took part in religious ceremonies, the

ashipum

(exorcist) cannot be considered a priest in the narrow sense of the term, since he served the public and notably the sick. The same remark applies to the

sha'ilum

, who interpreted dreams, and even more the

barûm

or diviner, a very busy and rich man in a society where divination was part of everyday life. Unfortunately, we know almost nothing about the temples of female deities. There is no doubt, however, that the temples of Ishtar, the goddess of carnal love, were the sites of a licentious cult with songs, dances and pantomimes performed by women and transvestites, as well as sexual orgies. In these rites, which may be found shocking but were sacred for the Babylonians, men called

assinu, kulu‘u or kurgarru

– all passive homosexuals and some of them perhaps castrates – participated together with women who are too often referred to as ‘prostitutes’. In fact, the true prostitutes (

harmâtu, kezrêtu, shamhâtu

), such as the one who seduced Enkidu (page 118), were only haunting the temple

surrounds and the taverns. Only those women who were called ‘votaress of Ishtar’ (

ishtarêtu

) or ‘devoted’ (

qashshatu

) were probably part of the female clergy.

12

In sharp contrast with all this were the

nadîtu

, who usually came from the best families and could marry but were not allowed to bear children so long as they remained in the temple ‘cloister’ (

gagû

) where they lived in communities. Loosely attached to the temple, the

nadîtu

were, in fact, remarkable business women who made fortunes from buying and letting out houses and land. On their death their wealth was left to their parents or relatives, thereby preventing the estates from being fragmented through the marriage of daughters.

13

All these people formed a closed society which had its own rules, traditions and rights, lived partly from the revenues of the temple land, partly from banking and commerce and partly ‘from the altar’,

14

and played an important part in the affairs of the state and in the private life of every Mesopotamian. Yet the days when the temple controlled the entire social and economic life of the country were over, for the vital centre, the heart and brain of the state, was now the royal palace.