An Unsung Hero: Tom Crean - Antarctic Survivor (32 page)

Read An Unsung Hero: Tom Crean - Antarctic Survivor Online

Authors: Michael Smith

Tags: #*read, #Adventurers & Explorers, #General, #Antarctica, #Polar Regions, #Biography & Autobiography, #History

The ice floe, once about one mile across, had been whittled away by the constant weathering and battering on their long drift. It had now shrunk to only 120 yards (110 m) at its widest and was only large enough for their filthy, slushy home, Patience Camp.

But, frustratingly, the pack refused to budge open. All day and night the men kept a constant vigil, eager to detect even a slight sign of sea swell which would signal free-flowing water and an end to their captivity.

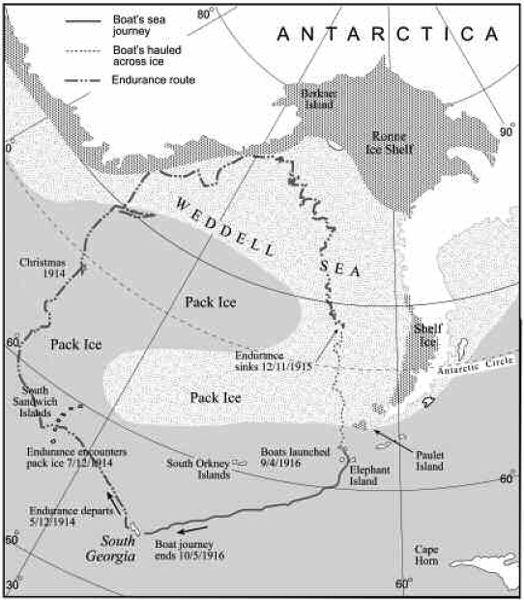

Endurance: The drift of the Endurance through the Weddell Sea and the expedition’s subsequent journeys to Elephant Island and South Georgia.

Over the following days they picked up the crucial signals for which they had been longing. The sea was taking over from the ice, the thin dark grey lines of open water getting larger by day and the floes all around noticeably melting. Despite adverse northerly winds that should have pushed them back to the south, they were still drifting slowly northwards, which indicated that the currents had taken control. Birds could be seen flying overhead, an encouraging signal that land was nearby.

On 7 April the peaks of Clarence Island, the smaller of the two islands, could be sighted some 60 miles (96 km) to the north. A little later the winds picked up, driving their slowly disintegrating floe against other larger chunks of floating ice. The constant battering of their vulnerable floating home spelt disaster for the castaways and it became increasingly apparent that the time for launching the boats had arrived – whether they liked it or not!

On Sunday 9 April, the men ate a hearty breakfast and the tents were taken down. Everything was poised to go. All that was required was open water.

By lunchtime their prayers were answered as sizeable leads of open water began to emerge alongside and at 1 p.m. the order came to launch the boats. The

Dudley Docker

and

Stancomb Wills

, packed with food and equipment, were the first into the water, where a small skeleton crew held them steady while the bulk of the party man-handled the heavier

James Caird

into the sea.

Worsley’s log recorded their position as 61° 56′ S, 53° 56′ W. The 28 men had spent almost six months on their fragile ice floe and drifted close to 2,000 miles (3,220 km) in a huge semi-circle around the Weddell Sea since

Endurance

was beset fifteen months earlier.

Miraculously, there had been no casualties. But as they pushed their boats into the bitterly cold, ice-strewn water the most hazardous part of their ordeal was ahead of them.

Launch the boats!

T

he three lifeboats pulled away from Patience Camp on 9 April 1916, the floe by now a small slushy little island of ice littered with the debris of humans who had spent almost six months attempting to make life as palatable as they could in the frozen wilderness. As they rowed, the ice around them began to close in again, shutting off lanes of open water and once again threatening their escape.

Some of the men rowed while others tried to push away great lumps of ice which drifted threateningly close to their vulnerable little vessels. It was soon clear that the men were dreadfully unfit and not up to the task ahead. The months of idleness at Patience Camp, coupled with the inadequate diet, had left them in no fit state for the hard work of rowing. At the same time, it was apparent that in raising the gunwales of the

Caird

and

Docker

, McNeish had inadvertently made them significantly more difficult to row.

But, to their profound relief, the little cavalcade of boats made some progress. The ice seemed to be receding and the amount of open, navigable water increased all the time. Moreover, although the men found the pulling very hard, the fatigue was to some extent offset by the warmth being generated by the exertion.

The

James Caird

, the largest and safest of the three, was in the lead. The boat, which was built in London to Worsley’s

specifications, was 22 ft 6 ins (7 m) long with a 6 ft (1.9 m) beam. Shackleton was in charge and he took with him another ten men, including Wild, McNeish, Hurley and Hussey. Next came the

Dudley Docker

, a 22-ft cutter built in Norway. There were nine men on board, led by Worsley and including Cheetham, Macklin and Marston.

Bringing up the rear was the

Stancomb Wills

, another cutter built in Norway, which was 20 ft 8 ins (6.3 m) long. Her beam was only 5 ft 6 ins (1.6 m) and she was barely 2 ft 3½ ins (0.7 m) from the inside of the keel to the top of the gunwale. Crammed inside her were eight desperate men, including Crean at the tiller.

In charge, nominally, was Hubert Hudson, navigating officer of

Endurance

. However, Hudson had struggled with niggling illnesses and the pressure of confinement on the ice floe, and was now heading for a nervous breakdown. Before the hazardous journey would finish, responsibility for the

Wills

would pass to the experienced hands of Tom Crean.

The imperturbable Irishman once again faced a crisis with equanimity and calmly rose to the occasion. As the difficulties worsened, he simply took control. It was, in many ways, similar to what he had done on the drifting ice floe to help rescue Bowers and Cherry-Garrard in 1911 and more recently, his heroic solo march to save the life of Teddy Evans in 1912. The difference was that previously Crean had displayed great courage by setting out alone to save other men. This time he was the leader, the skipper in charge of a tiny lifeboat struggling against the odds to combat the labyrinth of broken ice and ensure the safety of the seven other men in his charge.

What was particularly impressive, once again, was Crean’s composure and mental toughness. His physical strength was, as ever, readily apparent. But at moments of great stress, it was his capacity to remain calm, think clearly and obey orders that served him. While some of the men in the little boat struggled to cope with the strain, Crean stood out like a beacon. Shackleton, who possessed a masterful ability to judge and

direct people, could not have chosen a better person to take the helm of the

Stancomb Wills

on the hazardous journey.

Crean’s seamanship was also to the fore as the little craft pulled away from their icy home. Hurley, who was in the

Caird

alongside Shackleton, remembered that the little flotilla was struck by an ‘ice-laden surge’ which threatened to capsize the more vulnerable

Wills

. He recalled:

‘One of these reached to within a few yards of the

Stancomb Wills

which was bringing up the rear end; disaster was only averted by the greatest exertion of her crew and Crean’s skilful piloting.’

1

As darkness closed in, the men had rowed a total of 7 miles (11 km), an extraordinary achievement in the circumstances. Rowing in the dark was far too dangerous even to contemplate with so many icebergs blocking their path. Therefore, it was decided to tie up the three boats alongside a lengthy floe which, as luck would have it, contained a seal. The boats were hauled onto the ice and the seal made a welcome hot meal of fresh meat for the tired men.

By 8 p.m. the men, except two on watch, were into their sleeping bags. But at around 11 p.m. they felt the swell of the rolling sea beneath them and new disaster threatened. The floe suddenly lifted and cracked. The crack ran straight through one of the tents where some men were sleeping and they heard a splash as one of the party tumbled into the freezing black water. Shackleton rushed forward to see a frantic wriggling shape, trapped inside the sleeping bag and doomed to drown. In an instant he thrust a powerful arm in the direction of the writhing mass and hauled the man and sleeping bag back onto the ice. A second later the two halves of the broken floe crunched together. The wriggling man was Ernie Holness, a tough Hull trawlerman, whose sole concern was that he had lost his tobacco.

There were no dry clothes for Holness so volunteers marched him up and down the ice floe in the darkness to

prevent him freezing to death in temperatures which had dropped to –12 °F (–24 °C). Throughout the night, the men could hear the crackling of his frozen clothing which sounded like a suit of clanking armour as he walked stiffly back and forth, grumbling about his lost ‘baccy’.

All the men were cold, of course, and the incident with Holness had reminded them of their vulnerability. Few slept easily for the remainder of the night.

The party was up at 5 a.m. with the first hint of light. But the news was not good. Ice floes had moved in during the night, threatening to trap them once again. Nor was there any sign of Clarence or Elephant Islands. Worsley reckoned the distance was between 30 and 40 miles (48–64 km). Three hours later, to the relief of all, the pack began to disperse and once again the boats were launched.

It was another fraught day of heavy pulling on the oars while at the same time, the men had to keep constant vigilance against the threat of being struck by a passing floe. The men were exhausted, freezing, wet and hungry. The boats were heavily overladen and moved sluggishly through the choppy seas, while the men continually struggled for an inch of comfortable space among the packing cases and supplies which were strewn about their feet. They were continually wet from the spray, which frequently froze to their clothing and encased them.

To add to their woes, many of the party were struck by diarrhoea from the uncooked dog pemmican they had been forced to eat. Relieving themselves was a dreadful ordeal. It meant dangling their rump over the side of the heaving, swaying boat and exposing their most tender parts to a cold drenching from the breaking sea and painful frostbite where they would least want it to strike.

The

Wills

, whose gunwales had not been raised by McNeish, was undoubtedly the most exposed to the lumpy seas. Waves constantly poured over the sides and the weary men were occasionally up to their knees in the freezing water, though some reckoned that the sea water was warmer than the

air. At the same time, the continuous salty spray left the makeshift canvas covering over the

Wills

smothered in a screen of ice, weighing her down even further into the sea. At regular intervals, men had to risk their lives by clambering forward in the rolling seas to chip away at the accumulations of ice.

Blackborrow, the stowaway, was developing severe frostbite in his toes because his leather boots offered no protection against the wet and Hudson had developed a mysterious and debilitating pain in his buttocks which was increasing his feelings of woe. Several others were showing emotional strain and the withering effects of exposure.

Shackleton realised that the

Wills

, despite Crean’s experience, was highly vulnerable and might lose touch with the other two craft. Crean had been trained on large steel battleships and although he had some experience of small boats, it was not his natural area of expertise. As a result, Shackleton fixed a line between the

Wills

and the

Caird

. It was a lifeline, for the

Wills

would probably not survive alone in the high rolling seas, shipping water and weighed down with growing layers of ice which now covered the boat.

Concern about the fate of the

Wills

was shared by the men in the two other boats and Hurley recalled their fears:

‘It seemed from moment to moment that we should have to part the line and leave her to her fate. Sir Ernest, in the stern, strained his eyes into the dark torrent and shouting at intervals words of cheer and inquiry: “She’s gone!” one would say as a hoary billow reared its crest between us.

Then against the white spume a dark shape would appear and through the tumult would come, faint but cheering, Tom Crean’s reassuring hail, “All well, Sir”.’

2

The icebergs were a constant threat to all three boats and it was also apparent to the experienced sailors that the vessels were dangerously overloaded in these choppy seas. There was no

alternative but to dump something and the only commodity they could jettison was food.

Shackleton slashed their supplies from three to two weeks. Green, the cook who performed wonders in the most trying circumstances, produced the best and largest meal they had eaten in nearly six months before they reluctantly left a pile of food on an ice floe.

They rose next day to find 20° of frost and great rolling seas. The ice floe on which they had spent a relatively contented night was being buffeted and broken by the angry seas. It was breaking up and disintegrating beneath their feet and they were unable to launch their boats because there were no leads of open water. The anxiety was acute.

It was not until late afternoon, with the light already beginning to dim, that they spotted a lead and could launch the boats off the floe and into the uninviting water. Shackleton was unnerved by the experience, fearing that they would become trapped on a disintegrating floe in waters where they could not launch the boats. As a result, he vowed never to spend another night on an ice floe.