An Unsung Hero: Tom Crean - Antarctic Survivor (3 page)

Read An Unsung Hero: Tom Crean - Antarctic Survivor Online

Authors: Michael Smith

Tags: #*read, #Adventurers & Explorers, #General, #Antarctica, #Polar Regions, #Biography & Autobiography, #History

There are no Eskimos from which to learn the art of survival in Earth’s coldest and most inhospitable environment and there are few indigenous inhabitants, though it is visited

by varieties of penguins, seals and whales. There are very few other living things beyond some algae, lichens and mosses, so all food and equipment has to be transported to the continent and carried along on any journey. Antarctica is also a land of extremes. Despite the ice sheet covering, it rarely snows and for much of the year the continent is either plunged into total darkness for 24 hours a day or bathed in full sunlight.

People down the ages had believed in the existence of Antarctica, or the Southern Continent, for perhaps 2,000 years before its presence was finally established. Long before its discovery, the ‘unknown southern land’ –

Terra Australis Incognita

– had entered mythology. Greek philosophers claimed that a giant land mass was needed to ‘balance’ the weight of the lands known to exist at the top of the earth. Since the Northern Hemisphere rested beneath Arktos (the Bear), the general belief was that the southern land had to be the opposite – Antarktikos.

Great sailors like Magellan and Drake flirted with the unknown southern land in the sixteenth century and two intrepid French explorers – Jean-Baptiste Bouvet de Lozier and Yves Joseph de Kerguelen-Tremarec – discovered some neighbouring sub-Antarctic islands in the eighteenth century. But it was Captain James Cook, arguably the greatest explorer of all time, who first crossed the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773, in his vessels,

Resolution

and

Adventure

. Cook never actually saw Antarctica – he sailed to within 75 miles of land – and was doubtful about the value of any exploration in such a frigid and hostile environment.

The earliest people to see Antarctica travelled on the expedition led by the Russian, Thaddeus von Bellingshausen, which on 27 January 1820 recorded the first known sighting. But Bellingshausen was unsure about his sighting and it was not until January 1831, that sealing captain John Biscoe circumnavigated the continent.

Sir James Clark Ross penetrated the pack ice which surrounds the continent for the first time in 1841 and sailed

alongside the frozen land mass in his ships,

Erebus

and

Terror

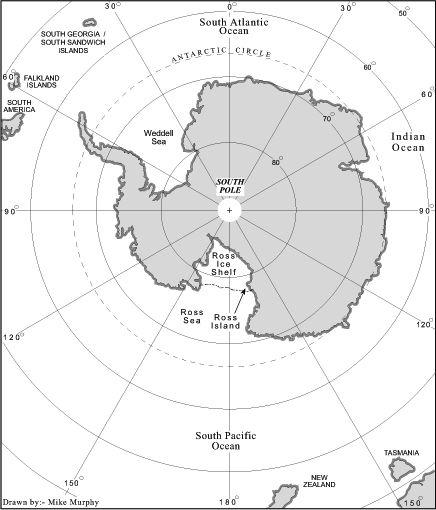

. He gave the names of his two ships to two of Antarctica’s most prominent mountains which stand guard over the entrance to the area that was to be frequented by several British expeditions around Ross Island in the Ross Sea.

An international expedition, led by the Belgian, Adrian de Gerlache, took the ship

Belgica

deep into southern waters between 1897 and 1899. His ship became stuck fast in the ice in the Bellingshausen Sea off the Antarctica Peninsula, which extends like an outstretched finger from the continent up towards the tip of South America.

Reluctantly and with great trepidation, de Gerlache and his crew were the first humans to spend the winter in the Antarctic, where the sun vanishes for four months. The hardship, bitter cold and endless gloomy months of total winter darkness took a heavy toll on the crew. One man died and two others were declared ‘insane’.

The survivors included a 25-year-old Norwegian, Roald Amundsen, and a 33-year-old American, Frederick Cook. Amundsen, the finest polar explorer of all time, would later complete the first ever navigation of the North West Passage across the frozen top of the North American Continent, and he would reach the South Pole a month before his ill-fated British rival, Captain Scott. Cook, a flawed but undeniably gifted character, would falsely claim until his dying day that he had beaten Robert Peary to become the first man to reach the North Pole.

The first landing on the Antarctic Continent outside the Antarctic Peninsula is thought to have taken place on 24 January 1895 when an eight-man party from the whaler,

Antarctic

, landed at Cape Adare. The identity of the first person to make the landfall has never been accurately established because of a series of disputes. But the naturalist, Carsten Borchgrevink, claimed to have leaped out of the rowing boat ahead of others to gain the honour of being first to place his feet on the Continent. Borchgrevink later went on

to secure the significant distinction of leading the first expedition to deliberately overwinter in Antarctica.

Borchgrevink, a Norwegian, landed near the entrance of Robertson Bay at Cape Adare on the Adare Peninsula in 1899 and erected two small prefabricated huts where his ten-man party was the first to spend winter on the Antarctic Continent. One hut, the party’s living quarters, still stands today. However, Borchgrevink’s exploratory deeds were modest and confined to a short trip onto the Ross Ice Shelf, or the Great Ice Barrier.

The first major attempt to explore Antarctica was conceived some years earlier by a remarkable English naval figure, Sir Clements Markham, who had made a brief trip to the Arctic decades before. Markham, an ex-public-school boy who entered the Navy at thirteen years of age, was on board the

Assistance

in 1850–51 during one of the many fruitless searches for Sir John Franklin’s party, which had tragically disappeared in search of the North West Passage in 1845 with the loss of all 129 lives.

It was an episode which shaped Markham’s colourful life and had profound consequences for Britain’s role in polar exploits, first in the Arctic and later in the exploration of the Antarctic Continent. Britain’s memorable part in the ‘Heroic Age of polar exploration’ would have been entirely different without the driving influence of the formidable bewhiskered Victorian patriarch, Markham.

Markham, a brusque and stubborn man who has been likened to a Victorian Winston Churchill, adopted polar exploration as a personal quest which bordered on obsession. There was a fanatical zeal about the way he manoeuvred, cajoled and expertly used his influence to ensure that Britain should undertake new expeditions south at a time when there was little support elsewhere for the idea. Moreover, Markham ensured that future exploration to the South would be a naval affair, when Britain could once again demonstrate its manhood and superiority to a slightly disbelieving world.

The Antarctic: the fifth largest continent was largely unexplored at the start of the twentieth century.

In particular, he was determined that the expedition would use traditional British methods of travelling, which meant man-hauling sledges across the ice, rather than the more suitable and modern use of dogs and skis. Dogs were quicker, hard working and at worst, could be eaten by the other dogs or the explorers themselves to prolong the journey or ensure safe return.

Markham, however, was typically sentimental towards dogs and implacably opposed to using them as beasts of burden at a time when others – notably the Norwegians – used the

animals to great effect. There is little doubt that he greatly influenced Scott’s lukewarm attitude to animals on both his journeys to the South, with the result that British explorers were destined to suffer the dreadful ordeal of man-hauling their food and equipment across the snow. The beasts of burden were the explorers themselves.

Markham, who loved intrigue, successfully engineered himself into the position as unelected leader of the venture but it took almost two decades to bring the first British expedition to Antarctica into fruition. In his celebrated

Personal Narrative

of events leading up to the

Discovery

expedition, he recalled:

‘In 1885 I turned my attention to Antarctic exploration at which I had to work for sixteen years before success was achieved.’

1

It was the first tentative step towards the British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901–04. It was also the opening chapter of Britain’s participation in the Heroic Age of polar exploration. Tom Crean was eight years of age at the time and Scott, Markham’s protégé, was sixteen.

Markham plotted and planned his Antarctic adventure with great determination, especially when it came to selecting his own preferred choice as leader of the first expedition. Although probably not his first choice, he had alighted on a young naval officer who was destined to carry his banner into the South – Robert Falcon Scott, or as he has become known, ‘scott of the Antarctic’.

Markham had been ‘talent spotting’ in the Navy for some years and finally selected Scott towards the end of the century, helped by a chance meeting near Buckingham Palace in June 1899. Writing in his famous book,

The Voyage of the Discovery

, Scott remembered:

‘Early in June I was spending my short leave in London and chancing one day to walk down Buckingham Palace Road, I espied Sir Clements on the opposite pavement,

and naturally crossed, and as naturally turned and accompanied him to his house. That afternoon for the first time I learned that there was such a thing as a prospective Antarctic expedition.’

2

Two days later Scott formally applied for the post as commander of the expedition, though he must have been given some indication from Markham that at the very least he was likely to travel with the expedition. In any event, Scott was not officially appointed until a year later on 30 June 1900 at the age of 32. It was the beginning of the Scott legend.

Markham, meanwhile, was busily trying to arrange the sizeable sum of £90,000 (equivalent to £8,000,000 at today’s purchasing prices) to pay for the expedition – the largest amount ever raised in Britain for a polar journey. This was a prolonged and frustrating exercise and only after lengthy debate and political manoeuvring was the cash found. Markham’s dream had become a reality.

The British National Antarctic Expedition was under way, complete with a new, purpose-built ship, the 172-ft long

Discovery

which boasted a steel-plated bow and 26-inch thick sides to combat the ice. It was to be a mixture of exploration and scientific research, although this, too, caused considerable friction between the sponsors, the Royal Geographical Society and Royal Society. Although there was some dispute over the expedition’s priorities, Markham’s will prevailed. Markham was unequivocal and insisted that the great object of the expedition was the ‘exploration of the interior of Antarctic land’.

Crucially, it was Markham who decided that Scott should explore the Ross Sea area which had been discovered 60 years earlier by Sir James Clark Ross and was to become forever associated with Britain’s polar exploration exploits during the Heroic Age.

Markham schemed and plotted at every turn, imposing his influence right down to the smallest details of the expedition. He even designed individual 3-ft long, swallow-tailed

flags or pennants which would be carried by the sledging parties on their journeys across the ice into the unknown.

With most squabbles now settled,

Discovery

left London on 31 July 1901 for the short trip to the Isle of Wight to participate on the fringe of Cowes Week and receive a royal farewell. The country was still coming to terms with the loss of Queen Victoria after her long reign and the new, but uncrowned monarch, Edward VII and his wife Queen Alexandra, came on board

Discovery

on 5 August to bid the expedition a royal farewell. Scott was impressed and recalled:

‘This visit was quite informal, but will be ever memorable from the kindly, gracious interest shown in the minutest details of our equipment, and the frank expression of good wishes for our plans and welfare. But although we longed to get away from our country as quietly as possible, we could not but feel gratified that His Majesty should have shown such personal sympathy with our enterprise …’

3

Discovery

, the fulfilment of Markham’s obsessive ambition and the opening chapters of both Britain’s Heroic Age and the Scott legend, sailed slowly away from the Isle of Wight at noon on 6 August 1901. She would not return home for almost three years.

On the other side of the world, Tom Crean was in the middle of a period of almost two years on board HMS

Ringarooma

, the P-class special torpedo vessel of 6,400 tons which formed part of the Royal Navy’s Australia–New Zealand squadron.

Ringarooma

, with the unlikely sounding name, was to be the unexpected launching pad for his remarkable Antarctic career.

The odd name for a ship in the Royal Navy arose from a special arrangement struck between Britain and Australia in the late Victorian age. Under the Imperial Defence Act of 1887, the Australians agreed to pay for the building of five warships for the Navy on condition that they were deployed in the seas around Australia and New Zealand.

Ringarooma

, built in 1890,

was crewed by Royal Navy personnel, but the Australians were given the right to choose their own names for all five ships.

Crean had joined

Ringarooma

on 15 February 1900 but before long had suffered an unfortunate brush with naval authority. On 18 December he was summarily demoted from PO to Able Seaman for an unknown misdemeanour, a rank he would retain for exactly twelve months.

4