An Anthropologist on Mars (1995) (27 page)

Read An Anthropologist on Mars (1995) Online

Authors: Oliver Sacks

One of Pontito’s many steep, angled stairways. Though very accurate, Franco’s painting (below) broadens the perspective, adding elements that a photograph (left) is unable to do.

One of Pontito’s many steep, angled stairways. Though very accurate, Franco’s painting (below) broadens the perspective, adding elements that a photograph (left) is unable to do.

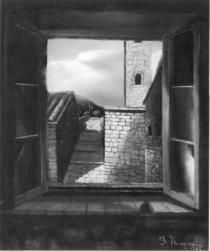

The view from Franco’s window, again showing composite perspectives.

The view from Franco’s window, again showing composite perspectives.

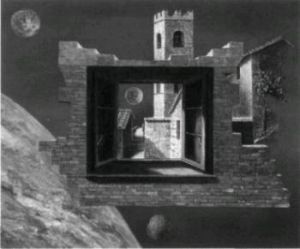

Two of Franco’s apocalyptic or “science-fiction” paintings, showing Pontito “preserved for eternity in infinite space.” The first shows the intimate view from his bedroom window; the second, a green-and-gold fragment of the church garden beneath a looming planet.

Two of Franco’s apocalyptic or “science-fiction” paintings, showing Pontito “preserved for eternity in infinite space.” The first shows the intimate view from his bedroom window; the second, a green-and-gold fragment of the church garden beneath a looming planet.

Precisely such an access to the past—a past preserved unchanged in the brain’s archives—was described to Wilder Penfield, so he thought, by some of his patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. These memories could be evoked, during surgery, by stimulating the affected part of the temporal lobes with an electrode; while the patients remained perfectly conscious of being in the operating room, questioned by their surgeon, they would also feel themselves transported to a time in the past, always the same time, the same scene, for any particular individual. The actual experiences evoked during such seizures varied enormously from patient to patient: one might re-experience a time of “listening to music”, another “looking at the door of a dance hall”, or “lying in the delivery room at birth”, or “watching people enter the room with snow on their clothes.” Because the reminiscence remained constant for each patient with every seizure or stimulation, Penfield speaks of them as “experiential seizures.”

87

87. It is now clear that though there are repetitive or reiterative elements in such seizures, there are always elements of a fantastic or dreamlike kind as well. (One such patient, described at the turn of the century by Gowers, would always see “a sudden vision of London in ruins, herself the sole spectator in this scene of desolation”, before having a convulsion or losing consciousness.) Penfield’s findings are discussed, and submitted to a radically different interpretation by Israel Rosenfleld, in The Invention of Memory.

He conceives that memory forms a continuous and complete record of life experience, and that a segment of this is evoked and played convulsively, involuntarily, during the seizures. For the most part, he feels that the particular memories activated in this way lack special significance, and are merely inconsequential segments activated at random. But on occasion, he grants that such segments might be more—might be particularly prone to activation because they are so important, so massively represented, in the brain. Was this, then, what was happening to Franco? Was he being forced to see, convulsively, frozen segments of his own past, “photographs” from his brain’s archive?

The notion that past memories endure in the brain, though in a somewhat less literal, less mechanical form, is an idea that haunts psychoanalysis—and the great autobiographers, as well. Thus Freud’s favorite image of the mind was as an archaeological site, filled, layer by layer, with the buried strata of the past (but one where these layers may rise into consciousness at any time). And Proust’s image of life was as “a collection of moments”, the memories of which are “not informed of everything that has happened since” and remain “hermetically sealed”, like jars of preserves in the mind’s larder.

88

88. In Remembrance of Things Past, Proust writes:

A great weakness, no doubt, for a person to consist entirely in a collection of moments; a great strength also; it is dependent upon memory, and our memory of a moment is not informed of everything that has happened since; this moment which it has registered endures still, lives still, and with it the person whose form is outlined in it

.

(Proust is only one of the great meditators on memory—wondering about memory goes back at least to Augustine, without any resolution, finally, as to what memory “is.”)

This notion of memory as a record or store is so familiar, so congenial, to us that we take it for granted and do not realize at first how problematic it is. And yet all of us have had the opposite experience, of “normal” memories, everyday memories, being anything but fixed—slipping and changing, becoming modified, whenever we think of them. No two witnesses ever tell the same story, and no story, no memory, ever remains the same. A story is repeated, gets changed with every repetition. It was experiments with such serial storytelling, and with the remembering of pictures, that convinced Frederic Bartlett, in the 1920

s

and 1930

s

, that there is no such entity as “memory”, but only the dynamic process of “remembering” (he is always at pains, in his great book Remembering, to avoid the noun and use the verb). He writes.

Remembering is not the re-excitation of innumerable fixed, lifeless and fragmentary traces. It is an imaginative reconstruction, or construction, built out of the relation of our attitude towards a whole active mass of organized past reactions or experience, and to a little outstanding detail which commonly appears in image or in language form. It is thus hardly ever really exact, even in the most rudimentary cases of rote recapitulation, and it is not at all important that it should be so.

Bartlett’s conclusion now finds the strongest support in Gerald Edelman’s neuroscientific work, his view of the brain as a ubiquitously active system where a constant shifting is in process, and everything is continually updated and recorrelated. There is nothing cameralike, nothing mechanical, in Edelman’s view of the mind: every perception is a creation, every memory a recreation—all remembering is relating, generalizing, recategorizing. In such a view there cannot be any fixed memories, any “pure” view of the past uncolored by the present. For Edelman, as for Bartlett, there are always dynamic processes at work, and remembering is always reconstruction, not reproduction.

And yet one wonders whether there are not extraordinary forms, or pathological forms, of memory where this does not apply. What, for example, of the seemingly permanent and totally replicable memories of Luria’s “Mnemonist”, so akin to the fixed and rigid “artificial memories” of the past? What of the highly accurate, archival memories found in oral cultures, where entire tribal histories, mythologies, epic poems, are transmitted faithfully through a dozen generations? What of the capacity of “idiot savants” to remember books, music, pictures, verbatim, and to reproduce them, virtually unchanged, years later? What of traumatic memories that seem to replay themselves, unbearably, without changing a single detail—Freud’s “repetition-compulsion”—for years or decades after the trauma? What of neurotic or hysterical memories or fantasies, which also seem immune to time? In all of these, seemingly, there are immense powers of reproduction at work, but very much less in the way of reconstruction—as with Franco’s memories. One feels that there is some element of fixation or fossilization or petrification at work, as if they are cut off from the normal processes of recategorization and revision.

89

89. Memory can take many forms—all, in their different ways, invaluable culturally—and we should only speak of “pathology” if these become extreme. Some people have remarkable perceptual memories, for example; they seem to take in automatically and to recollect without the least difficulty all the rich details of a summer holiday, the scores of people met, the way they dressed, their talk—the thousand incidents that make up a day on the beach. Others retain no memories (and perhaps lay down no memories) of such matters, but have huge conceptual memories, in which vast amounts of thought and information are retained, in highly abstract, logically ordered form. The mind of the novelist, the representational painter, perhaps tends to the former; the mind of the scientist, the scholar, perhaps to the latter (and, of course, one may have both sorts of memory, or varying combinations). Pure perceptual memory, with little or no conceptual disposition or capacity, may be characteristic of some autistic savants.

It may be that we need to call upon both sorts of concept—memory as dynamic, as constantly revised and represented, but also as images, still present in their original form, though written over and over again by subsequent experience, like palimpsests. In this sense, with Franco, however sharp and fixed the original, there is always some reconstruction in his work as well, particularly in the most personal pictures, such as the view from his bedroom window. Here Franco brings into an intensely personal and aesthetic unity a range of buildings that cannot be seen (or photographed) all at once, but that he has observed, lovingly, at different times. He has constructed an ideal view, which has the truth of art and transcends factuality. Whatever photographic or eidetic power Franco brings to it, such a painting always has a subjectivity, an intensely personal cast, as well. Schachtel, speaking as a psychoanalyst, discusses this in relation to childhood memories: