Amphetamines and Pearls (14 page)

Read Amphetamines and Pearls Online

Authors: John Harvey

I stood balanced and in mid-swing: my own eyes were still sharp on their target.

âEveryone back to the far wall. And keep your hands high, high, high.'

Tom Gilmour stood at the doorway. His feet placed slightly apart, both hands tight round the Magnum that was aiming behind me, aiming at Jupp who was holding the boy's Luger in his skinny hand. He had been about to shoot me in the back of the head. Then the room was full of cops.

Tom came over and lowered my arms from the position in which they had stuck. He lowered them and took the bayonet from my grasp. Took it and dropped it to the floor with a clatter. Then he turned to the Negro who had not moved, except to attempt to stem the flow of blood.

Gilmour looked at the cut in his right hip and kicked him in the leg just below it.

âAll right, you black mother-fucker, shift your arse over to that wall!'

15

Vonnie was wearing a white blouse that buttoned up to the neck and ended in a cute little frilly collar. She had on a plain black skirt and she was sitting beside me changing the plaster on my cheekbone.

Her hands were small and cool and I liked the feel of them on my face. Still I flinched when the plaster came away from the bruised skin and she tutted at my babyishness. She leaned her head over towards me and put her lips alongside the centre of the bruise; she ran her kiss down the cut. It was good to close my eyes and concentrate on that. On that and nothing else.

I needed to forget a lot of things: I needed to forget whose mouth was moving over me like warm silk.

âDo the police think it was this John who killed Candi, or do they think it was Thurley?' She was whispering in my ear. âAfter all, didn't you say that Thurley's gun was the one which shot her?'

I moved my head an inch away. Her mouth came after it. I tried again.

âThe same kind.'

âWhat do you mean? I thought you said it was the same gun.'

I kept my eyes away from her face.

âI said the same calibre gun. That doesn't make it the same weapon.'

She slid her hand over my arm and began to nestle up to me.

She said: âSo they don't know for sure who did it yet?'

I said: âYou're showing a lot of concern.'

She said: âWell, I did pay you to find out, or had you forgotten that?'

I stood up and walked a few paces away. I felt safer out there.

âNo, Vonnie, I hadn't forgotten that. In fact, that was one thing that made me uncertain for longer than perhaps I should have been.'

Those clear innocent schoolgirl eyes were looking straight at me.

âUncertain about what, Scott?'

âThat you killed your own sister.'

The room was suddenly very cold: a shiver swept through me and the hair at the back of my hands began to crackle slightly. The smile moved off her face to be replaced by something that was a mixture of fear and hate. Then these, too, disappeared and the winning smile returned. She got up and came towards me; put her hands on my arms and raised herself to her toes. One of her hands crept up behind my neck and pulled my face down on to hers. She kissed me for a long time, her tongue hotly probing my mouth as though she were trying to get inside my mind. I let myself go limp and she was kissing nothing and she let go of me and stepped half a pace away.

Her face crumpled and the tears came; she wiped at her cheeks with the back of one of her smooth little hands.

Through her tears she said: âOh, why do you accuse me of such a â¦' and then the tears returned and stopped her saying more.

I didn't know whether she was playing at being Mary Astor on purpose, or whether she had seen âThe Maltese Falcon' so many times that she said the words unconsciously.

But I had seen it too.

âThis isn't the time for that schoolgirl act!' I replied. âYou've been trying that on ever since I first saw you and it just won't work on me any more. So don't stand there forcing tears out of your face and looking like a virgin martyr!

âAt first I couldn't work out why, Vonnie, until I remembered seeing your face a long time ago. It was at a party at your house and I was there with Candi and I was kissing her and I opened one eye and caught sight of you watching us. I knew that if you could look at us with such hatred in your eyes, such jealous hatred, then you were not the sweet unspoilt little thing you were busy making out to be.

âJealousy like that doesn't vanish, Vonnie, along with childhood games and comics: it stays, it germinates, it grows inside until it swamps the person it's thriving in.'

The tears had stopped now and she was just standing there, listening and looking up into my face and I didn't have any idea at all what she might be thinking.

âYou must have got to thinking about what Martin was doing those nights he came home late from meetings about his new business. And, besides, a woman can tell when her husband is having another woman.

âSo you made it your business to find out. And you found out that he had been seeing your sister. And the jealousy you would have felt about anyone else was compounded inside your heart until there was only one way of letting it all out.

âAnd that way was through a .32 calibre hole into the middle of Candi's back.'

The look in her eyes was changing now: I thought it might have been like this when she had called on Candi.

âCandi rang me as she was afraid of getting a nasty visit from one of Jupp's boys, then how pleasantly surprised she must have been to see her sister on the doorstep. Only she didn't know that you had a gun in your handbag.'

Vonnie said, âScott, you don't have to â¦'

She reached up for me and kissed me again, but my mouth was closed and my face was like stone. She pulled her face away and looked at me with hatred in her schoolgirl eyes.

I knew the script. I knew there should be a knock on the door and I would say, âCome in', and then the door should open and a cop would be standing there and I would say, âHello, Tom'.

But I hadn't said anything to Tom. Or to anyone else. Yet.

Vonnie was sitting on the settee, staring at her handbag. I went forward and picked it up by the handles and held it out in front of me.

âIs it still there, Vonnie? The little gun you killed her withâCandiâAnnâwhatever you called her when you did it. Is it still there?'

I dropped the bag down on to the settee in front of her, without opening it.

I didn't look at her face again: I didn't want to see what was in her eyes.

I turned and walked to the door. Opened it. Walked out into the street. The wind was still cold and once again I pulled my overcoat collar up round my neck and hunched down my head. Looking for the warmth that was so difficult to find.

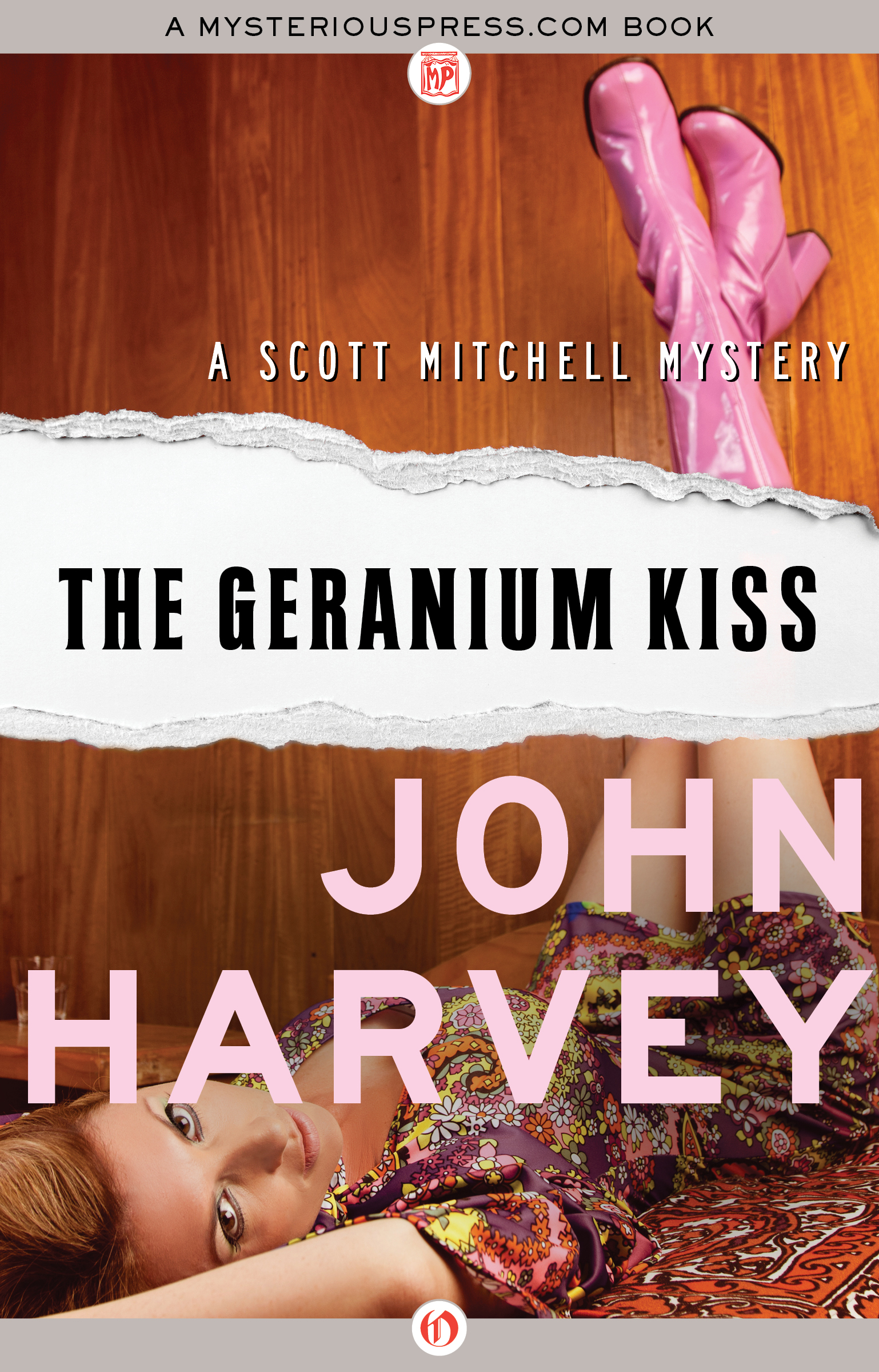

Turn the page to continue reading from the Scott Mitchell Mysteries

1

It was nine minutes after eleven and I was lying in a bath tub of water, that was gradually becoming the same depressing shade of grey as the sky outside. Or my last memory of it. But then, most of my memories were that colour.

It was early December and after pretending for a long time that it wasn't going to happen, it was winter. Summer had been hot and long; Autumn had produced reds and golds the brightness of kids' picture books. Just when everything had conspired to lull folk into a false sense of securityâwham!

The thing that annoyed me most was that I had been surprised. I shouldn't have been. I'd been around long enough to know that life worked like that. Maybe I'd been around too long. Thirty-six years too long.

No. It hadn't all been like that. There was a time back there, somewhere. Four years less than four days. â¦

Something cut in on my self-pity. Downstairs the phone was ringing. Another thing I should have known. No-one would call for days. Then when I took a bath there would be enough bells ringing to make me think I was the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Not that I'd ever worked out whether the best thing to do was to jump out of the bath, grab a towel and run down the stairs or wait until they phoned again later.

If it was important they'd call again.

Maybe.

Maybe they'd just move on through yellow pages to the next private investigator in the book.

I stayed where I was. There's something about your own warm dirt which is eternally consoling. I guess in the end it has to be.

The phone stopped ringing. I began to apply my mind to the great human problem of how the hell I was going to pass the time until there was a reasonable chance of getting to sleep for the night.

I could walk down to the coffee shop and indulge myself in blueberry shortcake; stay home with my stereo and a book of bridge problems; wait in the bath until my skin began to flake off into the water

Â

â¦

The phone cut across my thoughts again.

Okay, I said to myself, let's go.

I splashed a good quantity of murky water on to the floor; pulled at a towel and secured it around myself at the third attempt; collided with the edge of the bath; half-ran, half-hopped down the stairs, almost slipping three steps from the bottom; grabbed at the receiver; in time to hear the phone cut off at the other end of the line.

I told the telephone exactly what it could do with itself and sat down on the stairs, drawing breath. Then I padded through into the kitchen and put water in the kettle, switched it on. Took down the glass jar of Columbian coffee beans and shook some into the electric grinder. Ground the beans, warmed the enamel pot. I measured the amount of coffee that went into the pot and the amount of water that followed it. Stirred everything up and set the pot on the cooker.

Now I could go upstairs and get dressed. It was five minutes off twelve o'clock.

At three minutes past midday the phone went again. Don't ask me why I noticed the time. Occasionally I get obsessive about little things like that. Once I swore to myself that I wouldn't be able to live unless I had scrambled eggs for breakfast every day. I had sworn I wouldn't be able to live without a whole lot of things.

But here I still was and it was a hell of a long time since I'd had scrambled eggs.

I took the phone off the hook.

âHello,' I said, âthis is Scott Mitchell.'

âWell, hello,' said someone somewhere, âI'm glad you're finally up.'

The speaker was female with the kind of voice that goes with all those ads for Martini and Bacardi and the other drinks I'd never really got around to. I wondered what she wanted from me.

âWhat do you mean?' I asked.

âWell, Mr Mitchell, you have been proving rather difficult to get hold of.'

âI've been taking a bath,' I explained.

âOh,' she said with a slight smirk in her voice, âthen that would make you even more difficult to get hold of.'

âThat depends where you had in mind getting a grip,' I said.

âThat depends what you've got that's worth the effort.'

She was rising in my estimation with every minute and that wasn't the only thing that was rising. It wasn't every woman who could make me feel randy over the telephone in the middle of the day. But perhaps I'd been taking calls from all the wrong people.

âAre you still there, Mr Mitchell,' the voice said, âor have you slipped away for a quick rub down?'

âA quick what?'

âA quick ⦠oh, forget it!'

âI'm trying to,' I said, âbut it's hard. There's this image in my mind that's most disturbing.'

âThe only thing I can suggest, Mr Mitchell, is that you take yourself in hand. There's nothing else I can do in the circumstances.'

There was a pause during which I was conscious of the sound of her breathing, then she added, âUnfortunately.'

âThere is one thing you could do,' I told her.

âWhat's that?'

âYou could tell me why you phoned. I'm sure it wasn't only to brush up on your telephone technique.'

âAre you telling me that my technique needs improving?' She managed to sound almost hurt.

âNot at all,' I replied, âbut I'll withhold my written reference until I've experienced it in person.'

âNow, Mr Mitchell, you're bragging! Don't tell me that you can write. I thought you were a big dumb private detective.'

âI am. But I'm one of the newer kind. Got smart and went to evening classes: reading, writing and elocution.'

âWhat happened to the elocution?' she asked.

âI dropped out of that one. The teacher would keep coming up behind me with a long, pointed stick. Something to do with my diphthongs.'

âYour what?'

âForget it,' I said, âI haven't used them in a long time. And you still didn't tell me why you called.'

âYou know a policeman called Gilmour,' she said.

I didn't know if it was a statement or a question, so I didn't reply. Just waited.

Finally, she carried on. âHe suggested that you might be the man to get in touch with. There's a little difficulty and we need some help.'

âWe?'

âYes.'

âMeaning you and your husband?'

âMeaning my employer and myself, Mr Mitchell. I no longer have a husband.'

âYou make it sound as though you lost him in a waiting room at Victoria Station.'

âActually, it was room 101 of the Royal Hotel. Now can we get on with business?'

âBy all means. What kind of difficulty do you happen to be in?'

She hesitated, then said, âI don't think I can discuss it on the phone, Mr Mitchell. Couldn't we meet?'

âI'm sure we could. But if you didn't want to talk about it on the phone, why didn't you go straight into my office?'

âI don't believe in trusting other people's recommendations too fully. I wanted to make my own assessment before arranging any kind of meeting. This is a very delicate affair, Mr Mitchell.'

âIn that case,' I said, âmaybe you'd better try someone else. I'm about as delicate as King Kong.'

âBut look how gentle he was with Fay Wray,' she replied.

I liked that. I liked a woman who'd seen a movie or two.

âSo what's your assessment?' I asked.

âWhere's your office?'

I gave her the address in Covent Garden and told her I'd meet her there in an hour and a half. She said it sounded a long time, but I figured that didn't matter.

Hard-to-get Mitchell, that's me.

âOne last thing,' I said.

âIt's Stephanie,' she said, âStephanie Miller.'

âHow did you know that was what I wanted?' I asked.

âIt wasn't,' she replied and hung up.

I poured myself some coffee and sat in the armchair. Yes, that's right, the armchair. I had visitors like starving people had food.

The coffee was a little strong by now, but that didn't matter. I sat there trying to picture what she might be like. Finally figured that she'd be above medium height, longish dark hair, strong face; good clothes over a better shape.

I considered calling Tom Gilmour at West End Central and asking him what it was all about. For no good reason, I decided against it. I could wait. I was the kind of guy who just thrived on surprises.

Why, I was already getting worked up about Christmas.

This year I might even get a present from someone other than myself.

After another cup of coffee, I got the car out of the garage and drove into town.

Since the vegetable traders had moved away from Covent Garden and the developers had threatened to move in, it was like walking around in some kind of ghost town. The painted iron work of the original market still survived and where properties had been demolished, kids had used the walls that surrounded the empty sites for a series of highly-coloured murals. Yet, despite all this, there was a deadness, a lack of reality about the place.

Maybe that was why I stayed there; why I still liked it. Or maybe that was because I couldn't afford an office anywhere else.

I pushed open the side door next to what had been a jewelry showroom and was now an empty space and another plate glass window waiting to be broken.

The stairs that led up to the first floor were dirty and looked as if they'd hadn't been swept in a long time. It was dark on the landing and I felt for the light switch. Nothing happened. I should have known.

The sign that had been painted on the frosted glass of the outer office door read, âScott MitchellâPrivate Investigator'. The capital letters had all begun to flake away slightly, as though they thought they were giving the place too good a name.

I pushed the key into the lock and let myself in. Three paces took me over to the inner door and I unlocked this as well. Both locks.

Nobody could say that I wasn't a careful man. Sometimes. Usually when it didn't matter.

I pulled up the shade at the window and looked down into the street below. No-one walked the pavements. No-one drove along the street. I turned away and sat down behind my desk, wondered if I could take yet another cup of coffee. Decided that I could. After all, I hadn't had lunch.

The water boiled just as I heard a car draw up outside. When I looked out of the window, I was staring down on to the top of a neat little sports job in two-tone blue. After a few moments, I got a second mug from the cupboard and set it alongside the first.

Then I sat back behind the desk and tried to look the way I guessed she'd want me to look.

She didn't look too surprised when she came round the door and saw me sitting there. But then, maybe her expectations hadn't been too high.

My own had and she came up to them in every way. Not only that, but I'd managed to get the description right in most detailsâonly the hair was fair rather than dark. She wore a mid-length dark purple skirt under a dark fur coat that certainly hadn't come from any jumble sale. She smiled and came towards me holding out her hand.

I stood up and accepted it, being a gentleman underneath all the tough, wise-cracking exterior. Her fingers were cool, her grip firm and confident. Her eyes were a kind of greeny-blue and they never left mine until we had both sat down.

âCoffee?' I asked, nodding my head in the direction of the percolator in the corner.

She made a face, as though anticipating some kind of gritty brown mixture, but said yes anyway.

Then she said, âYou live a long way from your office, Mr Mitchell.'

âI like to leave work far behind me,' I said, âthe only thing is that it has ways of chasing after me.' I tried my second-best smile. âOh, and won't you make that Scott. Mr Mitchell sounds too formal.'

âIf you don't want your work to follow you home,' she said, âwhy have your home number in the book as well as this one?'

âI guess, Stephanie, that I can't afford to turn down the possibility of being hired. If you see what I mean.'

âI see what you mean,' she replied. âOh, and won't you call me Miss Miller?'

I blinked and got up to pour out the coffee. By the time I had brought it back to the desk, she had lit up a cigarette. I hesitated a moment, waiting for her to offer me one so that I could refuse, but she didn't give me the opportunity.

I looked down at the way she had hitched the hem of her skirt above her knees and wondered what kind of opportunities she might give me. If any.

âThat's not bad,' she said after sipping from the edge of the cup as though it might turn the tables and bite her. âNot bad at all. Maybe you ought to be in the restaurant business?'

âSorry,' I said, âI already have a good business.'

She looked around the office. âWhere do you keep it?' she asked. âThis really is a good front.'

I laughed a little and drank some of the coffee. She was right. It was good and business wasn't. I tried to picture myself in a white apron pouring morning coffee and calling out for some more slices of home-made apple pie at the same time. I didn't like what I saw.

I said, âMaybe what you've brought will help things along a little. Do you think we can talk about it now ⦠or are you frightened that the place is bugged?'

Ostentatiously, I looked under the desk for a hidden recording device. As I did so, she crossed her legs easily and pleasantly.

âAre you really feeling for something under there?' she asked. âOr is that just an excuse to look up my skirt?'

I grinned. âIt could be both.'

She said, âLook, do you want me to tell you why I'm here or not?'

I shrugged my shoulders. âIt'll do. For now.'

She picked up her coffee cup and held it in both hands in front of her, not drinking from it, simply holding it. I wondered what it was about the things she had to say that made her need that kind of support, that kind of comfort.