Among the Bohemians (6 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

For some Bohemians, the distinction between borrowing and downright dishonesty became blurred.

Cheques were bounced, shops lifted, hotel bills left unpaid by fleeing guests.

Constantine Fitzgibbon expended considerable ingenuity in cheating the gas company.

He inserted twenty-five centime pieces into the meter, which worked if you gave it a sharp tap at the same time.

He also discovered to his joy that if he placed a sixpence on the railway line which ran a few hundred yards from his tumbledown cottage near Buntingford, the train would squash it to the size of a shilling, and the gas meter would not differentiate.

There were those who took the view that possessions were bad, so it was all right to take them off people.

Philip O’Connor broke open his sister’s gas meter and went off with the proceeds without any compunction.

In the thirties, the critic Geoffrey Grigson and his wife took pity on the indigent Fitzrovian poet Ruthven Todd, ‘an unhealthy-looking grey oddity’.

Grigson had often wondered how this Bohemian kept alive – he seemed to have no visible means of support.

Eventually he fathomed that Ruthven supported himself by stealing.

[He was] a thief, an innocent, honest literary thief.

He wouldn’t have picked your pocket or burgled.

Books and manuscripts were his game, not from shops, but from friends or those who befriended him.

Unaware, the Grigsons let Ruthven a room in their house for ten shillings a week in the belief that a job he then had reviewing books would cover this paltry sum.

One day Grigson was chatting to a bookseller acquaintance in his shop off the Charing Cross Road.

The bookseller mentioned that he had bought for ten shillings a batch of second-hand books, one of which happened to contain a letter to Grigson.

A few weeks later, the bookseller pointed out another strangely familiar batch of books which he had bought from the

same seller.

It was Ruthven Todd.

Grigson paid ten shillings and bought them back.

This arrangement persisted for some time; Todd filching his landlord’s books from the top shelf where he was least likely to notice their absence, selling them and paying his rent back out of the proceeds; Grigson then retrieving his possessions for payment of the same sum.

We never taxed the Innocent Thief with his theft, this generous creature who seldom came to see us without some present, paid for God knows how, for the children.

Thus by shifts and expedients and the generosity of friends the Bohemian ekes out a dependent survival; Grigson’s patient collusion in what the bourgeois world would undoubtedly see as a reprehensible offence, his warm-hearted appreciation of Ruthven’s essential honesty and niceness, leaves one feeling the world to be a better place.

*

One of the most noticeable and cheering things of all as one delves into accounts of Bohemia is the ready assumption among the better-off that if you had money you were honour-bound to help those who had none.

And even if you had no money at all – like Dylan and Caitlin Thomas – you despised bourgeois tight-fistedness:

Avarice, meanness, stinginess were the worst of all crimes for us… We ourselves were never mean.

We bought drinks liberally round the house, on tick… It is easy not to be mean when there is nothing in the kitty to be mean with.

The more that is in the kitty, the more difficult it is, apparently, not to be mean.

It was of course an attitude that reduced them speedily to a state of utter dependency.

Friends’ open-handedness must have saved many an impoverished artist from despair.

Take Augustus John; it was he who spotted Kathleen Hale’s talent and gave her the post as his secretary, at two pounds a week, so that she could give up scratching a living doing odd jobs and find more time for her own work.

Or take Maynard Keynes, who tactfully subsidised two of his best friends, both in money difficulties, the painter Duncan Grant and the writer David Garnett.

Keynes insisted that a deed of covenant made out to Grant should be dependent on an equivalent deed made out to Garnett, thereby ensuring that each felt impelled to accept the money, because refusing it would jeopardise the offer to the other.

Keynes also contributed

heavily towards the cost of running the Bell country house, Charleston.

Roger Fry was another philanthropic friend to penniless artists: it was partly their plight that persuaded him to start the Omega Workshop in 1913, as a way of providing hard-up artists with a minimal income.

A similar enlightened attitude prevailed when Helen Anrep, Fry’s mistress, was left after his death in reduced circumstances – an unmarried ‘widow’; Vanessa Bell and others clubbed together to buy her a reconditioned refrigerator.

The story is well known of how Virginia Woolf and Ottoline Morrell – deeply impressed by reading

The Waste Land

– set up a fund to release T.

S.

Eliot from the necessity of working in a bank (help which he rejected as insufficient).

It is only one among many heartening examples of altruism in the artistic community.

Long before he was famous, Lytton Strachey was supported financially by his friend Harry Norton.

The painter Dorothy Brett regularly paid Mark Gertler’s rent for him.

The editor Edward Garnett, having located a cheap cottage for W.

H.

Davies to live and write in, paid for the poet’s fuel and light out of his own pocket.

Numbers of young artists – Gertler, Nash, Meninsky, the poets Rupert Brooke and Isaac Rosenberg – had reason to be grateful to the patron Eddie Marsh, who bought their work, had them to stay and helped them out in innumerable ways.

Edward Wads worth was a painter who had inherited a fortune, and he and his wife Fanny entirely supported the Vorticist leader Wyndham Lewis during his most impoverished period.

But Lewis found it hard being an object of charity.

Regrettably, one week the expected sum of money failed to materialise, whereupon Lewis scrawled an ungracious postcard to his benefactors bearing the words:

Where’s the fucking stipend?

Lewis

Lewis later became dependent on the reluctant charity of Dick Wyndham (no relation), an aspiring artist of substantial independent means, who felt exploited by Lewis’s rapacity.

The writer took revenge on his patron, portraying him in

The Apes of God

(1930) as a vile charlatan with deviant sexual tastes, and that was the end of that friendship.

Patronage took many forms.

Dick Wyndham’s cousin David Tennant, a cultured socialite, made life easier for artists in the way he knew best, by starting the Gargoyle Club, which he specifically aimed at a Bohemian clientèle, keeping the prices deliberately low.

Rudolf Stulik, the Austrian

patron

of the famous Eiffel Tower restaurant, applied a Robin Hood principle, charging people what he thought they could afford.

The tactic eventually

bankrupted him, and though the artists set up a fund to bale him out, he was forced to leave his restaurant.

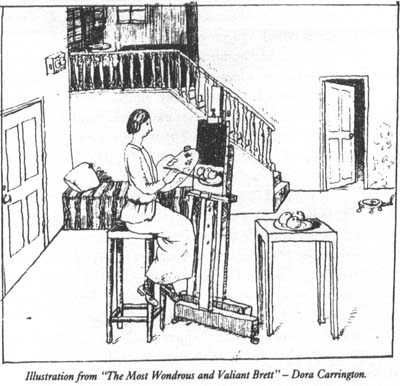

Illustration from “The Most Wondrous and Valiant Brett” – Dora Carrington.

Carrington pays homage to her friend Brett, at work in her sparse studio.

The

gas ring at floor level was a common feature of rented rooms.

Established writers like Edmund Gosse, George Bernard Shaw and John Galsworthy were notably generous to younger authors in distress, producing loans and handouts.

They were also luminaries of the Royal Literary Fund, which gave grants to writen in desperate straits: in 1910

£

1,650 was raised to help authors who had ‘turned their back on the prospect of pecuniary gain’.

There was of course no certainty of subsidy for all; in 1925 Liam O’Flaherty was rescued from the brink by a cheque for

£

200, but in 1938 Dylan Thomas was turned down.

Unfortunately there was no equivalent fund for artists, and with no state-funded safety-net, the Bohemian social network could be a lifeline for those who were desperate.

Somebody usually knew somebody who could help, rally others, organise a temporary whip-round – even if they themselves were little better-off.

It was the compassionate Viva King who set up an appeal to rescue her old friend Nina Hamnett from utter destitution.

Nina Hamnett had spent a lifetime only just keeping her head above

water – or perhaps, in her case, whisky.

A splendidly buoyant and sociable character, she appears in innumerable memoirs of the period; she was the Ur-Bohemian, uncrowned ‘Queen of Bohemia’, first lady of Fitzrovia.

In 1911 she rebelled against her middle-class background, and scraping by on the fifty pounds advance on a legacy from her uncle, plus two shillings and sixpence a week donated by some kindly aunts, she launched into the London art world with a vengeance.

Her exuberance and spontaneity won her a wide circle of friends at the Café Royal, including Augustus John, Walter Sickert, Roger Fry and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and she soon conquered Paris, where she became an habituée of the left bank cafés, a friend of Modigliani, Picasso and Cocteau.

She was an admired painter, but her real gift was for living life to the full.

By the thirties Nina, a fixture in the Fitzroy Tavern, was virtually a tourist attraction in her own right.

Yet she was always penniless.

There are endless stories of her getting stranded in Paris unable to pay for her hotel, sitting in bars waiting for acquaintances to turn up to pay her mounting drink bill – though often she would have preferred a square meal.

Ruthven Todd helped out when she couldn’t afford clothes by printing a circular for her which read

WHAT DO YOU DO WITH YOUR OLD CLOTHES

?

Do you give them to the

SALVATION ARMY

or the poor?

If so,

DO NOT REMEMBER NINA.

But as her youthful resilience waned, the issue of her poverty began to get more serious.

Her talent had degenerated but she never lost her good spirits

wrote Viva King.

The smallest happening in her life was enlarged to happy proportions.

About 1937 I heard she was living in extreme poverty and a friend and I started a fund to help her…

They sent a circular to all Nina’s friends suggesting that everyone should contribute half a crown a week to keep her going.

The fund got off to a good start, but after a while the goodwill started to wear thin as it became clear that there was no other remedy for Nina’s poverty.

Eventually only Viva herself and one or two others were still loyally keeping the bailiffs at bay.

Viva acknowledged that Nina, despite her dissolute ways, was capable of giving great joy, and saw no reason why she should be abandoned by the old friends who had had such good times in her company over the years.

For Nina, despite having to live in bug-infested rooms with at times only

boiled bones and porridge to keep her from starvation, was munificent when she had money.

As a true Murger-style Bohemian, Nina would blow any money that came her way on ‘ruinous fancies’.

Her name had become well known in the newspapers after she had been sued for libel by the notorious diabolist Aleister Crowley in 1934.

*

One day after this when Nina was sitting in the Fitzroy Tavern, Ruthven Todd walked in with a copy of a popular paper, and pointed out to her a photograph captioned ‘Miss Nina Hamnett, artist and author… takes a walk in the Park with a gentleman friend’.

The caption was inaccurate, for the lady with the unnamed male friend was in fact Betty May.

Nina jumped up, borrowed the newspaper and half a crown for a taxi, and dashed to Fleet Street where she demanded settlement for libel; to avoid trouble the paper promptly gave her twenty-five pounds.

Before long she was back at the Fitzroy Tavern where she opened a tab for all comers.

When Betty May walked in Nina instantly plied her with whisky; the astonished Betty wondered where all the largesse was coming from, and as soon as she found out she too was on her way to Fleet Street threatening writs.

The paper obliged, forced to admit that their photograph of her was wrongly captioned, and she was soon back at the party with another twenty-five pounds.

The celebrations went on well into the evening, by which time both women were back to their usual penniless state.

In her autobiography Nina rather wistfully reflected that her reckless attitude to money came about from her middle-class upbringing – ‘being brought up as a lady and taught never to mention money’.

Unfortunately, such artlessness had dire consequences.

Poverty is bad enough, borrowing could suffice as a means of struggling by, but serious grown-up debt was no laughing matter.

For one proud spirit debt was a way of life.

When he was at Oxford the young writer Arthur Calder-Marshall became friends with an eccentric spinster known to him and his fellow undergraduates as ‘Auntie Helen’; they attended her tea parties and sat at her feet while she expounded to them on poetry and philosophy.

In due course it dawned on Calder-Marshall that Auntie Helen was practically starving.

He gently offered to give her some money.

The old lady was indignant; she had learnt over a lifetime how to survive on nothing, and she was not going to start compromising now:

‘… I don’t want your money and I’ll tell you why.

As an Artist who will have to fight the Philistines all your life, the sooner you learn this the better.

Remember:

PROVIDED YOU ORDER THE BEST, THERE’S NO NEED TO PAY FOR IT

.’