Among the Bohemians (56 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Defiance of convention took here the form of a retreat from unthinking modernity, and yet Acton remained all his life an original, who never lowered his sights from the high altar of Beauty.

It was Ottoline Morrell’s steadfast worship at this same altar that was to make her, for some, an object of ridicule, while others remembered her as one of the most influential and inspiring women of her time.

Ottoline confronted illness and bereavement with courage and determination, and soon after her death one young protégé wrote to Philip Morrell of ‘her love

for all things true and beautiful… no one can ever know the immeasurable good she did’.

In her old age Rosalind Thornycroft’s appearance did not betray how brightly her passions had burned in youth.

It was hard to imagine the fragile, bird-like old lady in a tweed skirt and genteel silk blouse as a wild romantic and Bohemian, smouldering with Wagnerian desires.

She and Godwin Baynes recovered from their shipwrecked marriage.

Godwin became a leading light in Jungian psychoanalysis, and had three subsequent wives.

Rosalind returned to England with the children, and found happiness in her marriage with another divorcé who also had three children.

In her sixties her desire for ceremony and beauty found its truest fulfilment when she joined the Roman Catholic Church.

‘She was an idealist first and last,’ remembered her daughter.

But life’s tragedies caught up with some of these idealists.

Vanessa Bell’s vitality and sense of fun were to take a blow from which they never recovered.

She was fifty-eight when her son Julian was killed in the Spanish Civil War, aged twenty-nine.

After that she became unsociable, reclusive even, escaping abroad when she could, finding respite only there or at Charleston with Duncan and her family.

She painted the garden, and her grandchildren, and flowers.

Her biographer concludes that, despite an apparent serenity, she was ‘walled up in her own feelings, isolated by her reserve and left profoundly alone’.

Nicolette Devas tried hard to hold on to her independent identity, her Bohemianism.

She felt the tug of the conventional world when she married Anthony Devas, but the John in her was never quite squashed.

‘There was no family tradition of self-control.

We had been reared among people who expressed their emotions in public without thought for the effect on others.’ It took the Second World War to beat Nicolette’s natural vitality into submission.

‘This war is going to kill the fun in me.

Never again shall I feel that lovely careless rapture.

I feel my youth dying.’ My frivolous grumbles proved to be true.

From twenty-eight I leapt to forty.

Nicolette’s memoir dwells passionately on the days of that lost youth, skimming over the post-war period in a few bleak chapters, as the heroes of her early life die one by one.

There is a similarly elegiac quality to the end of Robert Medley’s memoirs, as he mourns the death of Rupert Doone, his lifelong partner.

In the 1930s Robert had given unstinting support to Rupert in his great experimental

venture, the Group Theatre, which produced a number of plays by Auden and Isherwood.

Their life and work together had, he felt, been revolutionary and important in its achievements.

The Second World War drove a wedge between the intense phase of Medley’s youth and the second half of his life, when he quietly immersed himself in painting and teaching, but despite this the lessons of his earlier experiences were never neglected.

It had been ‘a time when I came to recognise standards and principles in a life of art that I have lived by ever since’.

But others refused to be beaten by life.

Stella Bowen and Ford Madox Ford separated.

In 1939 he died, and with the threat of war Stella and their daughter returned to England and found a cottage on a remote part of the East Anglian coast.

In it Stella reassembled objects from their travels – glass beads, a desk, paintings – which evoked her past life.

But regret was not in her nature.

Resilient and buoyant, she believed powerfully in the possibility of happiness.

Even with the bombers flying overhead Stella looked to the future full of curiosity and optimism:

Meanwhile we continue to fight for our existence.

And we are getting nicer all the time, so that even a poor stuck-up painter can feel sisterly towards football-fans and people who eat prunes and tapioca.

Surely that is an improvement!

There are people in the world who will not make compromises with life.

Their faces are turned like sunflowers towards the source of light, and even when battered and broken they refuse to give in to old age, sorrow, loss, defeat.

Nancy Cunard was one.

‘She was a good hater, and of course at the same time she loved things and people very deeply.’ Nancy lived on, in pain and barely able to walk, skeletally thin, still drinking rough red wine and smoking Gauloises.

Her ivory bracelets were crumbling, but she was honest, high-bred and angry to the end.

Her peripatetic life ended in Paris in 1965.

Kathleen Hale was another.

Though early poverty took its toll on her health, she was one of the survivors.

If her marriage was a disappointment, her two little boys brought her fulfilment, as did her success with the children’s stories about Orlando the Marmalade Cat, which she wrote and illustrated.

When Kathleen was seventy-eight she went to Buckingham Palace dressed in second-hand chinoiserie and an astrakhan hat from a charity shop, decked with a Moroccan necklace hung with coins and glass beads, to accept an OBE from the Queen: Bohemia triumphant.

She died in 2000 at the age of a hundred and two.

‘Iris Tree was the most truly Bohemian person I have ever known’ was

Daphne Fielding’s verdict on her close friend.

After her break-up with the handsome Austrian aristocrat who was her second husband, Iris found herself adrift with very little money.

She travelled in Italy, Greece and Spain, and friends supported her.

A small role playing herself in Fellini’s

La Dolce Vita

gave her enough money to survive for a while.

One rainy day in the fifties, Daphne bumped into her in a Venetian trattoria:

Suddenly she made her appearance, wearing a Galloway skirt of scarlet flannel, a black tabard and, for want of a better word to describe her headgear, a ‘runcible hat’ which appeared to be made of thick translucent indiarubber jelly set in a hat-shaped mould.

At her heels, a black familiar, was Aguri [her Belgian sheepdog].

Both of them were dripping wet.

In this memoir of Iris, Daphne Fielding dwells on her friend’s idealism, her insatiable desire for experiment and the starry-eyed romanticism which, even on her deathbed, never left her.

Iris’s last words – (she died in 1968) – were, ‘It’s here, it’s here… Shining… Love… Love… Love…’

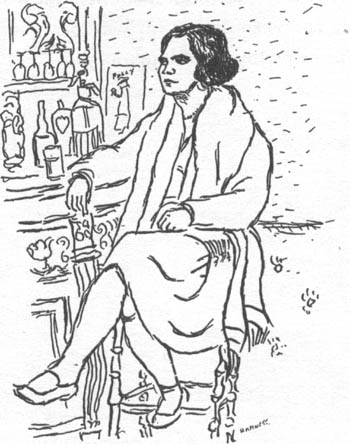

Betty May at the Fitzroy Tavern, by Nina Hamnett.

Betty May’s ghosted memoirs,

Tiger Woman

, came out in 1929.

Concluding, she wrote: ‘My feeling about my life is in many ways one of great dissatisfaction.’ The lows seemed to have outnumbered the highs, and

yet Betty’s irrepressible liveliness led her to conclude that fate had played its part in bringing her sorrow, for how could she have behaved differently?

Against this hidden but all-powerful influence it seems to me impossible and foolish to rebel.

It has brought me joy and it has brought me sadness.

No doubt it will bring me both again, but I am sure that I am born for adventure, and in the future I shall be able to face these things as I have faced them in the past.

One can only hope that Betty’s adventurous spirit sustained her through the hardship and dependency that seem to have dogged her into old age.

Her beauty faded and time took its inevitable toll on her energies.

There was a third marriage – she reappears briefly in the nineteen thirties as Betty Sedgwick, living in Hampstead – and a fourth, for she made it through World War Two, and surfaced again as Betty May Bailey.

But the trail was going cold; she withdrew.

Arthur Calder-Marshall tried, and failed, to find her.

The friends of her youth died or lost touch.

All but one: Bunny Garnett never forgot his early flame, the fascinating model for Claire in

Dope Darling

.

He remained true to the best spirit of Bohemia and helped her when she fell on hard times.

Reduced to a modest council house in Kent in the 1970s, Betty eked out her last years living on handouts from the state, a small stipend from her one-time lover, and memories.

Appendix A

Monetary Equivalents

In order to get some idea of what artists lived on in the period discussed in this book, the following figures, which give approximate equivalents of one old penny and one pound to today’s money (2001 figures), may be useful:

£ | £ | |

1900 | 0.25p | £ |

1905 | 0.26p | £ |

1910 | 0.25p | £ |

1915 | 0.19p | £ |

1920 | 0.10p | £ |

1925 | 0.15p | £ |

1930 | 0.20p | £ |

1935 | 0.22p | £ |

1939 | 0.21p | £ |

Source: John J.

McCusker, ‘Comparing the Purchasing Power of Money in Great Britain from 1600 to Any Other Year Including the Present’, Economic History Services, 2001, URL:

http:/www.eh.net/hmit/ppowerbp/

Appendix B

Dramatis Personae

The following notes do not aim to be encyclopaedic; there are omissions and failures of knowledge.

They are intended as an aide-mémoire for the reader who may appreciate extra briefing on some of the extensive cast of characters who appear in this book.

With this in mind, these deliberately abbreviated resumés emphasise their subjects’ context in the world I have called Bohemia, as opposed to their achievements, artistic or otherwise.

Acton, Harold (1904–1994)

Brought up in Italy and schooled at Eton, the author of

Memoirs of an Aesthete

(T948) frequented ‘haut Bohemia’ in the company of his Oxford contemporaries Evelyn Waugh and Peter Quennell.

Acton’s creed was culture, his predilections for the European and the exotic, for modernism and homosexuality; these marked him out as a nonconformist if not exactly a Bohemian.

Aldington, Richard (1892–1962)

‘I [never] wholly shuffled off the bourgeois… I should say I was naturally the eremitical kind of bohemian.’ Aldington’s semi-autobiographical novel

Death of a Hero

(1929) satirised both worlds with equal acerbity.

Aldington started as a poet; he was friends with Pound, F.

M.

Ford and D.

H.

Lawrence, and lived much of his later life in France.

Anrep, Boris (1883-1969)

Anrcp left his native Russia in 1908 to study art in Paris, and there fell in with Augustus John’s circle, including his future wife, Helen Maitland.

His mosaic on the main staircase of the National Gallery in London includes portraits of several illustrious contemporaries.

Despite living in a ménage-`-trois with Helen and his mistress Maroussia, Anrep remained a sought-after figure in high society.