America's Greatest 20th Century Presidents (25 page)

Read America's Greatest 20th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Charles River Editors

Kennedy speaking to the country about the Cuban Missile Crisis

For the next four days, President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Khrushchev were engaged in intense diplomacy that left both sides on the brink. Europeans and Americans braced for potential war, wondering whether any day might be their last. During that time, however, the Soviets used back-channel communications through Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy seeking a way for both sides to reach an agreement and save face. Finally, on October 28

th

, Khrushchev and Kennedy agreed to the removal of the missiles, under U.N. supervision. In exchange, the U.S. vowed never to invade Cuba, while privately agreeing to remove intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that had been stationed in Turkey, near the Soviet border, under the Eisenhower Administration. Realizing how close they had come to disaster, the Americans and Soviets agreed to establish a direct communication line, known as the “Hotline”, between the two sides in an effort to avoid nuclear catastrophe resulting from miscommunication.

Despite the foreign policy failures of Kennedy's first year and a half in office, the Cuban Missile Crisis significantly increased the Administration's credibility on foreign policy matters. By fending off Soviet aggression, Kennedy renewed the America’s commitment to defending the Western Hemisphere and repositioned the nation with strength. Prior to the crisis, the Soviets had viewed the Kennedy Administration as weak, especially for its timidity on Fidel Castro. The Cuban Missile Crisis was in part a result of Kennedy's prior failure; the Soviets thought they could push the Americans in Cuba. By averting nuclear war and removing the Soviet missiles from Cuba, Kennedy's political popularity improved, and he was again lauded for his foreign policy achievements.

Nuclear Testing and West Berlin

Throughout his presidency, Kennedy made repeated efforts to negotiate a treaty banning nuclear testing with the Soviets. At Vienna in June 1961, Kennedy held his ground until he and Khrushchev reached an informal agreement against nuclear weapons testing. While this was initially hailed as a success, it fell apart just months later when the Soviets began testing nuclear weapons in September, and began sending them to Cuba the following year. In 1962, after almost 40 months of negotiations led by the United Nations Disarmament Commission, negotiations between the US and the Soviets again failed to come to a conclusion on nuclear weapons testing.

By the summer of 1963, however, after nearly five years of talks, the US, Great Britain and the Soviet Union finally agree to a limited ban on nuclear testing. This treaty halted testing in the atmosphere, outer space and under water, but not underground. It was quickly ratified in Congress.

During that same summer, another East-West controversy had come to the fore: the Berlin Wall. Build in 1961 to prevent East Berliners from venturing into West Berlin, the Wall had come to serve as a symbol for global division.

In June of 1963, Kennedy travelled to West Berlin, where he gave his famous Berlin Wall Speech. In it, he said “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words: Ich bin ein Berliner.” In the speech, Kennedy reiterated the American commitment to Berlin and West Germany. It was very well received by Germans, and it helped to solidify the alignment of Western Europe with the United States against the Soviets.

The Civil Rights Movement

It took a lawsuit, but finally he was set to attend the University of Mississippi. James Meredith was still a young man in 1962, and thousands of young men attended the university each year. But as he repeatedly attempted to enter campus that September, he was prevented by a mob, which included Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett. Governor Barnett had earlier attempted to stop Meredith’s admission by changing state laws to ban anyone who had been convicted of a state crime. Meredith’s “crime” had been false voter registration. On September 30, Meredith was escorted by U.S. Marshals sent in by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. A white mob attacked the marshals, and nearly 200 people were injured. President Kennedy had to send in the Army to allow Meredith to stay at school. Meredith would receive a bachelor’s degree in political science in August 1963. He would later be shot in the back and legs during a civil rights march in 1966 by a white man attempting to assassinate him.

While the bulk of Kennedy's legacy deals with foreign policy, significant domestic upheavals were occurring in the United States during his Presidency. Most important among these was the Civil Rights Movement.

Kennedy's record on civil rights is mixed. In the House and Senate, he often sided with conservative Southern Democrats. And though he ran for President in favor of civil rights, he didn't believe his narrow victory gave him a mandate for decisive action on the issue. For most of 1961 and part of 1962, Kennedy essentially made no movement on civil rights, despite the spread of protest and action, led by Martin Luther King, throughout the South.

Nevertheless, Kennedy and his brother Robert often found themselves forced into action by conflict between authorities and minorities and protesters in the South. After ensuring Meredith’s attendance in 1962, a similar situation broke out in 1963, when Alabama's Governor George Wallace personally prevented two African-American students from enrolling in the University of Alabama. Again, Kennedy sent in federal troops against the state's Governor.

In between these events, Kennedy had proposed a limited civil rights act that focused primarily on voting rights, but it avoided more controversial topics of equal employment and desegregation. Kennedy was toeing the line between maintaining political support in the South while also holding liberal Democrats. Until the end of his Presidency, however, a coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans prevented any action on the bill, and Kennedy was never able to sign it into law.

Apart from civil rights, Kennedy made some headway on other domestic policy issues. He successfully passed an increase of the minimum wage and aid to public schools. Otherwise, though, most of Kennedy's New Frontier proposals failed to pass through Congress, including his Medicare bill. It would fall upon his successor, Lyndon Johnson, who had spent the 1950s mastering Senate parliamentarianism, to enact much of the New Frontier in the form of the Great Society. And it would be Johnson who pushed forth more stringent protections on civil rights than Kennedy had ever proposed.

Chapter 5: Kennedy’s Assassination

By November of 1963, President Kennedy was not overly popular nationwide. His foreign policy had a number of successes, but Americans had also not forgotten the failures of 1961 and early 1962. Furthermore, his tepid support of civil rights was dividing his own party, between liberals and conservatives. Southern conservatives thought Kennedy had proposed too much, while liberals didn't think voting rights went far enough. The strains would eventually undo the former Democratic coalition of the previous 80 years, done in with the help of Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” in the late 1960s, which saw the South turn solidly Republican at the expense of losing minority support.

Such division was showcased especially in the state of Texas. Liberal and conservative Democrats were divided there, which threatened to reduce Kennedy's chances of carrying the state's 25 electoral votes in the 1964 election. To shore up reelection prospects, the President travelled to the state to cool disagreements and rebuild his support.

November 22, 1963 started as a typical Friday, and many Americans were unaware that President Kennedy was heading to Dallas, Texas in preparation for his reelection campaign. Jackie and the President arrived in Dallas in the morning, and were surprised by their warm reception. Kennedy's meetings with top Democratic officials also went well, and Kennedy felt reassured that Texas would be behind him in 1964.

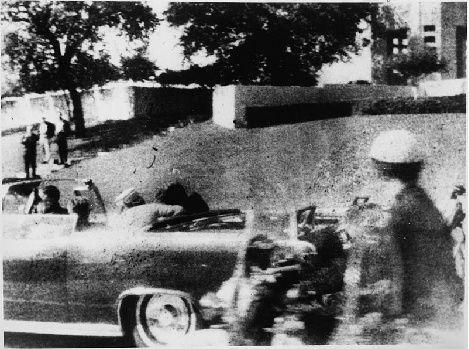

That day, Kennedy chose to keep the presidential limousine’s top down to feel connected to spectators. Around 12:30 p.m., Texas Governor Connally’s wife turned behind to the first couple and said, “Mr. President, you can't say Dallas doesn't love you.” But as the motorcade slowed down while turning a corner to enter Dealey Plaza, it came into the sightlines of a sixth floor window at the School Depository building. There, Lee Harvey Oswald, a Communist sympathizer, had set up a sniper’s nest with a high-powered rifle. With the motorcade traveling at low speed, Oswald’s first shot hit Kennedy in the upper back, traveled through his body, and struck Governor Connally’s arm in the front passenger seat. The bullet would come to be referred to by conspiracy theorists as the “Magic Bullet”.

As Kennedy hunched over, a confused Jackie moved toward him to check on him. Oswald’s next shot missed the motorcade, but Oswald’s next shot was a direct hit, shattering Kennedy’s skull. Of course, chaos reigned supreme as the motorcade quickly sped out of the Plaza and headed for a hospital, with a Secret Service agent famously jumping onto the back of the limousine as it sped away. But it was far too late.

Aside from the spectators who turned out to greet Kennedy and his wife at Dealey Plaza, some of the first people to find out about the shooting in Dallas were those watching the soap opera

As the World Turns

on CBS. In the middle of the show, around 1:30 p.m. EST, Walter Cronkite cut in with a CBS News Bulletin, announcing that President Kennedy had been shot at and was severely wounded.

The news began to spread across offices and schools across the country, with watery eyed teachers having to inform their schoolchildren of the assassination in Dallas. Most Americans left school and work early and headed home to watch the news. Even the normally stoic Cronkite couldn’t hide his emotions. Around 2:40 p.m., misty eyed and with his voice choked up, Cronkite delivered the news that the president was dead.

That day, stunned Americans wondered if the assassination was a Soviet conspiracy, a Cuban conspiracy, or the actions of a lone nut. Time and investigations haven’t fully resolved all of the questions. The country never fully recovered from the President’s assassination, which still remains one of the most mysterious and controversial events in American history.

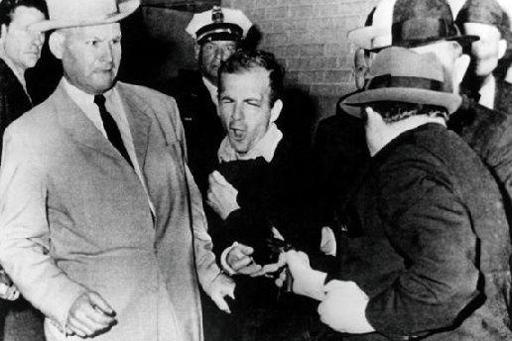

Oswald was arrested hours after Kennedy’s shooting, after he shot and killed Officer J.D. Tippit. In fact, Oswald was initially arrested for Tippit’s death, not Kennedy’s, and he claimed he was a “patsy” who had killed neither man. Two days later, Oswald was being transported through the basement of the police’s headquarters when nightclub owner Jack Ruby stepped out of the crowd and shot Oswald point blank in the chest, killing him on live TV. The Warren Commission later investigated the Kennedy assassination and ruled that Oswald was the lone assassin, but the bizarre sequence of events have ensured that the Kennedy assassination is still widely considered one of the great mysteries of American history, with conspiracy theories accusing everyone from Fidel Castro to the mob of orchestrating a hit.