America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (6 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Jefferson's election to the Presidency also left an important electoral legacy. By 1800, the Alien and Sedition Acts had made Adams an unpopular President, especially in the South. Without formal parties to effectively nominate candidates in a President-Vice President ticket, the Democratic-Republicans had two nominees: Thomas Jefferson and New York's Aaron Burr, who had been tabbed to serve as Jefferson’s Vice President. Once the Electoral College cast its ballots, Jefferson and Burr had the same number of electoral votes with 73, while Adams came in third with 65.

This was, however, a mix-up. The Democratic-Republican electors were supposed to have one elector abstain from voting for Burr, which would make Jefferson President and Burr Vice-President. In the 1800 election, states selected their electors from April until October. The last state to select its electors, South Carolina, selected Democratic-Republicans but neglected to have one voter abstain. The final vote was thus a tie.

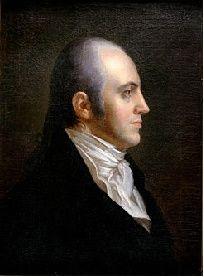

As the Constitution prescribed, the election was determined in the House of Representatives. This proved problematic as well. The Federalists controlled the House that decided who would be President. With Jefferson as their arch-nemesis, they were hardly happy to support him, and many initially voted for Burr. The first 35 ballots were always a tie between Burr and Jefferson. Not until mid-February of 1801, when Alexander Hamilton, another of Jefferson's nemeses, came out to endorse the Vice President, did Jefferson come out ahead. Hamilton’s disdain for Burr was so strong that he virtually handed the presidency to Jefferson, who had been his ideological opponent for the better part of a decade. Hamilton’s decision created personal animus between Hamilton and Burr that stewed for years and famously culminated with the duel that ended Hamilton’s life in 1804.

Aaron Burr

On February 17

th

, 1801, Thomas Jefferson was elected President on the 36

th

Ballot in the House of Representatives.

Inauguration, War, and an Annual Message

Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated as the third President of the United States on March 4

th

, 1801, the first inauguration held in Washington, DC. Even the new capital owed its existence to Jefferson; in the Compromise of 1790, Madison, Hamilton, and Jefferson reached a compromise that would allow the federal government to assume the states' war debts in exchange for creating a new capital in the South.

Within just months of his swearing-in, a little-known nation declared war on the United States. On May 14

th

, the Pasha of Tripoli declared war on the U.S. after Jefferson refused to give more than the $80,000 that had been previously agreed to in a treaty. Under Washington and Adams, the US had paid nearly $2 million dollars to North African nations to allow American ships to conduct commerce in the Mediterranean. The US never declared war on Tripoli, but Jefferson did send a naval squadron to the area. The conflict, known as the First Barbary War, officially ended in 1805.

At the end of the year, Jefferson was charged with informing Congress of the State of the Union, a Constitutional requirement. Unlike his predecessors, who gave a speech to a joint session of Congress, Jefferson simply sent a note. Every President followed this precedent until Woodrow Wilson in 1913, creating the political spectacle that Americans today associate with the State of the Union Address.

Marbury v. Madison

In the 1800 election, Thomas Jefferson defeated the incumbent President, John Adams. It would be one of the first times, if not the first time, that the political party in power handed over power to its political opponents peacefully. But the Federalists had one more card to play. Before Jefferson took office, Adams and Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which modified the Judiciary Act of 1789 to allow Adams to name several additional judges to lower courts while reducing the number of Supreme Court justices. Adams had already lost reelection, but Jefferson would not assume office until March, giving Adams time in his lame-duck period to fill the newly-created circuit judge positions with Federalists in the remaining two weeks of his Presidency. They became known as “Midnight Judges.”

The day before Jefferson took power, Adams named dozens of new judges and justices of the peace, one of whom was William Marbury. When Jefferson took office, he instructed his Secretary of State, James Madison, not to deliver those commissions, stalling the appointmenst.

Marbury sued the government asking the Court to compel Madison to deliver his commission. Instead, the Court found the Judiciary Act of 1789 itself was unconstitutional, pulling Marbury’s chair out from under him. This was the first time in U.S. history that the Supreme Court exercised its authority to review laws passed by Congress or state legislatures. Judicial review had been established, the most important power the Supreme Court still holds today.

Adams’s actions had outraged Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, but so did the Supreme Court’s decision. Jefferson wrote quite forcefully that the Supreme Court was one of the greatest threats to democracy, with judicial review opening up the ability for the Court to become its own kind of tyranny.

The Louisiana Purchase

The crowning achievement of Thomas Jefferson's first term, and his entire Presidency, was undoubtedly the Louisiana Purchase.

Purchasing Louisiana was not easy. The Louisiana territory was disputed between France and Spain. Spain, which still owned land on the west coast of North America in the early 1800's, hoped for a buffer zone between itself and the United States. The Louisiana land – the area surrounding the Mississippi River – was the perfect buffer. Before the Revolution, France ceded the territory to Spain following the French and Indian War. But in 1800, Napoleon reacquired the territory in exchange for giving Spain a piece of Tuscany, which Napoleon claimed he could conquer.

Napoleon, however, gave up on his campaign in Tuscany. Angry, the Spanish closed off all commerce with the French on the Mississippi River. This deeply affected the nearby United States. Though the country did not yet own the river, it still conducted extensive trade along its waters.

Jefferson would not tolerate restrictions on American trade in the west. He was also wary about having Napoleonic territory right next door. Deeply Republican, Jefferson had witnessed the origins of the French Revolution, and was thoroughly disappointed that Napoleon's dictatorship was the end result.

Prior to his Presidency, Jefferson's most successful endeavors had been in writing the Declaration and conducting diplomacy in France on behalf of the new nation. He put the skills he learned in the latter experience to good use in negotiating the purchase of the Louisiana Territory. Jefferson dispatched Secretary of State James Monroe to France, where he was able to meet Napoleon at just the right time. Napoleon's armies were failing in the West Indies in 1803, and he was hoping to recoup his military campaigns and focus exclusively on Europe. He was thus open to relinquishing the Louisiana Territory.

Under the terms of the deal, the U.S. paid a total sum of 15 million dollars, which came out to about 3 cents per acre. The Louisiana Purchase encompassed all or part of 15 current U.S. states and two Canadian provinces, including Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, parts of Minnesota that were west of the Mississippi River, most of North Dakota, nearly all of South Dakota, northeastern New Mexico, northern Texas, the portions of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide, and Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, including the city of New Orleans. (parts of this area were still claimed by Spain at the time of the Purchase.) In addition, the Purchase contained small portions of land that would eventually become part of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The purchase, which doubled the size of the United States, comprises around 23% of current U.S. territory. The population of European immigrants was estimated to be 92,345 as of the 1810 census.

The purchase was a vital moment in Jefferson’s presidency of Thomas Jefferson. Regardless of how favorable the deal was, Federalists found fault with it. They did not think the Constitution gave the President the authority to purchase and govern additional territory. Although he felt that the U.S. Constitution did not contain any provisions for acquiring territory, Jefferson decided to purchase Louisiana because he felt uneasy about France and Spain having the power to block American trade access to the port of New Orleans. Jefferson decided to allow slavery in the acquired territory, which laid the foundation for the crisis of the Union a half century later.

On the other hand, Napoleon Bonaparte was looking for ways to finance his empire’s expansion, and he also had geopolitical motives for the deal. Upon completion of the agreement, Bonaparte stated, "This accession of territory affirms forever the power of the United States, and I have given England a maritime rival who sooner or later will humble her pride."

Lewis and Clark

In August of 1803, with the Louisiana Purchase now complete, Jefferson commissioned an exploration of the territory. The purpose of the expedition was to explore not only the Louisiana Territory, but also the land beyond, to look for waterways that could open opportunities for the United States to trade with Asia. Additionally, Jefferson hoped to gain information about the continent's natural and geographic resources.

Jefferson chose two Virginia-born veterans of Indian Wars in Ohio – Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. During their explorations, they were accompanied by a Shoshone Native American woman named Sacajawea.

President Jefferson had long envisioned the goal of western expansion. He knew that Europeans had not yet made claims on the Northwest Territory – the modern day Pacific Northwest – and hoped to claim that Americans had “discovered” the land and thereby take ownership of it. By assembling a knowledge base of the terrain and its resources, Jefferson thought the United States could strengthen its claim to the land.

From 1803 until 1806, Lewis and Clark travelled through modern-day Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas and onto Montana and Oregon. They relied heavily on the knowledge of local Indian tribes and formed relations with over two dozen Indian nations. Using rivers as tributaries, the pair was able to return home to Missouri rather quickly from the Oregon coast of the Pacific Ocean. They published their findings in a journal. Although the territories would eventually be disputed by Russia, the Lewis and Clark expedition led the U.S. to effectively expand its territorial claims even farther than the Louisiana territory.

Amendment and Reelection

Jefferson's doubling of American territory was an immensely popular move. Before he could steamroll forward with reelection, however, Congress needed to prevent a similar mishap to the one that had occurred in the election of 1800. Another tie would diminish confidence in the functionality of the US Constitution. Congress thus passed the 12

th

Amendment on December 12, 1803. It established separate ballots for the election of the President and Vice-President. This ended the system of having the second place finisher become Vice-President.

The election of 1804 proved favorable to Jefferson. His Federalist opponent, Charles Pickney, was from South Carolina, which alienated some of the New England base of the Federalist Party. Jefferson easily defeated Pickney with 162 electoral votes to Pickney's 14. Until that time, no candidate had won more electoral votes in the nation's history (though Washington had been a unanimous selection), and the effects of the 12

th

Amendment obviously skewed the greatness of Jefferson's reelection. Regardless, though, Jefferson won most of the states – all but Delaware and Connecticut – meaning he even carried most of Federalist New England and New York. He also won all of the newly admitted states – Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee.

Foreign Policy in the Second Term

Jefferson's second term in office, despite his overwhelming mandate to govern, was relatively uneventful, but he did have to deal with some significant foreign policy problems during his second term. Most important among them was a dispute about naval rights on open seas. The British Navy, which had been the dominant naval power on the planet for over a century, proved supreme in controlling the navigation of ships on the oceans around the world. They routinely stopped American ships, captured sailors, and forced them to serve in the British Navy. Hoping to halt this, Congress passed a resolution condemning British impressment in February of 1806. In April, Congress banned the importation of some – though not all – British goods to the American market.