America's Dumbest Criminals (15 page)

The conductors and the engineers all saw a man go down, and they were sure the train went over him. They assumed he had been killed. But somehow after the train had managed to stop, the dumb, drunk, and incredibly lucky criminal was still alive.

To this day, no one is sure exactly how it happened. The train might have knocked the man down, or he might have passed out on the tracks. But the important thing is that he was lying

between

the two rails when the train went over him.

Said Hawkins, “Now, there's always stuff hanging down under a train, like air hoses and stuff, and those things did clip him and roll him around. He was bruised, scratched, and cut, and his clothes were torn. But he was all right. He was up and walking aroundâstill drunk and scared out of his mind. I took him in for his own protection and arrested him for public intoxication.”

My Name's Steve, and I'll Be Your Dealer Today

G

iving one more glance around the crowded bar, Agent Johnson (who's still working undercover in the South somewhere and shall therefore remain otherwise nameless) yawned and sighed. He was working undercover narcotics and had wanted to bust a certain known dealer that night. But the dealer had never appeared. Whatever the reason, the whole evening had been a colossal waste of time.

The agent was about to pay his tab and go home when a man slid onto a stool next to him and struck up a conversation. Johnson began to suspect that this man might also have connections to the drug culture.

“Hey, man,” he asked his new acquaintance, “you know where I can buy some reefer?”

The man said evenly, “As a matter of fact, I do.” After a few more minutes' conversation, Agent Johnson understood that the man was referring to himself.

By now Johnson was wondering,

How am I going to find out who this guy is?

He had to have a name in order to serve a warrant. And he had to serve a warrant, because to arrest the man on the spot would jeopardize the entire operation and blow his cover as well.

The new suspect didn't feel comfortable selling drugs in the bar, so they strolled outside into the parking lot. The man led Johnson to his car. The agent was still racking his brain, trying to think of a way to learn the dealer's name.

Then the dealer himself solved the problem.

“Listen, man, it's nothing personal,” he said. “But I don't know who you are. I mean, you could be a cop for all I know. So can I see your driver's license?”

With a rush of relief, the agent pulled out a phony driver's license that he used for undercover work. And then he said, “Hey, I don't know who you are either. Can I see

your

driver's license?”

“Sure,” the dealer replied.

The agent looked at his license, memorized the information, and made the buy. About a week later, the dealer was treated with a personalized warrant for his arrest signed by his new friend, Johnson.

I

n a Florida town, the first policewoman on the local force was sent undercover to crack down on the prostitution problem. Her particular targets were the “johns,” or clients, who are considered as much a part of the problem as the prostitutes themselves. (After all, it's just as illegal to buy it as it is to sell it.) The police officer was dressed to look like a “working girl,” wired for sound, and sent out to walk the streets. It wasn't long before a well-dressed man picked her up.

“Are you a cop?” the man asked her.

“Do I look like a cop?” she responded.

“Well, no, you look too nice to be a cop.”

So the conversation continued, and the man eventually told the undercover officer what he had in mind. But that wasn't enough to arrest him for solicitation, however. He also had to offer to pay her.

“What's in it for me?” the officer asked.

“Well, normally,” the man said, “I don't pay more than fifty dollars. But as good as you look, I'd pay you a hundred bucks.”

The officer leaned down and spoke into her hidden microphone, “Fellows, did you hear that? I knew I could make a whole lot more money doing something besides being a cop.”

The man was flabbergasted. “You are a cop!” he yelled.

The female officer looked at him smugly. “Yes, I am.”

“Hell!” the man exclaimed. “If you'd have told me you're a cop, I would've offered you two hundred bucks. I've never screwed a cop before.”

“You've been screwed by one now,” the officer remarked. “You're under arrest.”

I

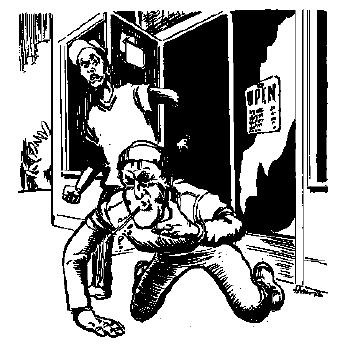

n St. Louis, Missouri, two men entered a convenience store with the intention of robbing it. They made their intention known to the clerkâbut they had no weapons. The clerk told them that if they didn't leave the store he would call the police.

Frightened that their robbery wasn't working out like the ones on television, the two crooks made a run for it. But one of the robber wannabes decided he was going to steal

something

âso he grabbed a hot dog off the rotisserie and quickly shoved the whole thing in his mouth.

A few steps outside the convenience store, the hot-dog thief collapsedâhe was choking on the frankfurter. Faced with this beautiful case of poetic justiceâit takes a weenie to stop a weenieâthe other man did the only honorable thing a dumb criminal can do. He ran like hell, leaving his partner gasping in the parking lot.

He grabbed a hot dog off the rotisserie and quickly shoved the whole thing in his mouth.

L

ate one evening, in a small town in Illinois, a taxi was called to a local bar to pick up a man who had imbibed a bit too heavily. The gentleman in question staggered out to the cab, gave his home address, and slouched back into the seat as the taxi pulled away from the curb.

When they arrived at the guy's house, the drunk told the cab driver that he didn't have any money on him, but that he had some in the house. “I'll just run in and be right back out with the money, okay?”

That was fine by the cabby; it happened all the time. But not quite this way.

The man got out of the cab, staggered into his house, and reappeared a few moments later.

“I couldn't find any money,” he slurred, “but I found my gun, so you're going to have to give me all

your

money.”

Believe it or not, this guy actually robbed the cab driver at gunpoint, took the money, and then lurched back into his house, leaving the cabby still parked outside.

You don't have to be psychic to see where this is going. The stunned and shaken cab driver backed his vehicle up about a block, called his dispatcher, and told them he had just been robbed at gunpoint, and then described exactly where the armed robber was at the very moment.

When the police arrived on the scene, the cabby repeated his story to them. Then he watched as the police approached the house, weapons drawn.

Pete Peterson was an officer on the force at the time. He remembers that the front door was wide open when the officers approached.

“Only the storm door was shut,” Pete recalls, “and it wasn't locked.”

The officers looked in through the storm door to the lighted living room. There on the coffee table was the .38-caliber handgun. And there on the sofa, passed out cold, was the robber.

The drunk was sentenced to five years in prison for armed robbery. He might as well have told the cabby, “Take me straight to jail.”

W

inning the lottery is every gambler's dream. So when Donna Lee Sobb hit the California state lottery for one hundred dollars she was thrilled. Not only did she need the money, but her winning ticket also qualified her for the big two-million-dollar jackpot.

Things were looking up for Donna, it seemed. She smiled as she looked at her picture in the local news-paper. She was getting some attention, and people on the street occasionally recognized her. Unfortunately for Sobb, so did the people on the beatâthe police beat, that is. A local cop read her story, saw her picture, and recognized her as the woman wanted by authorities on an eight-month-old shoplifting warrant.

Now Sobb

really

needed that hundred dollars she had just won. She ended up applying it toward her bail.

The Civic-Minded Cocaine Cooker

I

t was October 1993 in a Georgia town when Tyrell Church was in the kitchen cooking up his specialty . . . cocaine. He had been doing that for a good thirty years, but he had never seen any that cooked up like this batch. Something was wrong.

“I had never seen powder cocaine that turned red when you cooked it up,” Church explained. So, being concerned for his own welfare as well as that of the public at large, Tyrell Church did what any fool would do. He took the suspicious concoction to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation crime lab for analysis.

The lab ran four separate tests. The substance proved to be cocaine after all. And Church was promptly arrested and charged with possession of the same. He opted to serve as his own lawyer in what to him seemed a ridiculous trial.

“Had I known I was going to be arrested,” he argued, “I wouldn't have taken it over to the lab.”

So why did Church take his cocaine to the lab?

“If kids get hold of something like this,” he said, “it might hurt them or poison them. I took it over there to have it tested to see if it had been cut or mixed with any dangerous substances.”

The civic-minded cooker went on to say that if something had been wrong with the cocaine, he could have warned the public.

Church insisted that he had often had his cocaine tested in New York, where he once lived.

“What's the sense in having a crime lab,” he asked, bewildered, “if a person can't take anything over there?”

He also requested that the substance be retested, a request which the judge denied.

“I'm not a habitual user,” the cooker complained in his final statement. “I use cocaine for my arthritis. It's a waste of the taxpayers' time for this kind of case to come to court. The grand jury shouldn't have even bothered.”

“I do not think a violation of the cocaine law is a waste of time,” the district attorney countered.

The jury couldn't have agreed more. It took just seven minutes for them to return a guilty verdict.

I

n Decatur, Illinois, a house had been burglarized by someone familiar with the familyâand familiar with where they kept their money. The cash was all in changeârolls of quarters, dimes, and nickels. And kept in the freezer.

During the investigation, one of the detectives was doing the necessary legwork of asking people in the neighborhood if they had seen or heard anything unusual or suspicious the night of the burglary. One person had noticed a car that was parked in the rear of the residence that evening and was able to provide a rather vague description of the vehicle.

Following up on that sparse lead, the investigator stopped by a neighborhood gas station and asked the attendant on duty if he'd seen a car that fit the vague description or seen anyone that might have looked suspicious to him that night.

“Well,” the clerk mused, “there was one fella who came in the station that night and paid for his gas in rolled change. I remember because the money was cold, real cold, like it had been in the freezer or something.”

Bingo! The detective asked the attendant if he could identify the man if he saw him again.

“Sure, I could,” the man stated. “He comes in here about every day or so and buys gas.”

The detective handed the clerk his card.

“If that guy comes in here again, I'd like you to get his license plate number.”

The very next day the clerk called with the tag number of the vehicle, and the suspect was quickly apprehended.”

“Can you believe it?” the detective asks. “I mean, the guy didn't even wait until the money had warmed up before he started spending itâand he only went one block away.”

D

uring the two years that Dan Leger worked undercover down South as a narcotics officer, he had more than his share of dumb criminal encounters. And he was constantly amazed at the “cop folklore” circulated among criminalsâthe widespread misinformation about the law and police procedure. He tells this story about his all-time favorite dope:

“I was working undercover narcotics, deep cover. I looked like the nastiest of the nasties. I infiltrated the independent bikers and tapped into some large distribution systems. Over the course of a few months I made several buys from a fairly large supplier. We got to be pretty good acquaintances.”