American Tempest (8 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

“He engrafted his self into the body of smugglers,” Justice Peter Oliver growled, “and they embraced him so close, as a lawyer and useful pleader for them that he became incorporated with them.”

16

To protect his own smuggling operations, merchant king Thomas Hancock and his nephew/partner John Hancock were among those who embraced Otis and even recommended him to their British counterparts who needed legal representation in America.

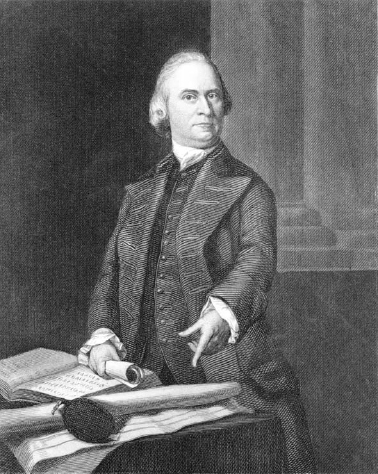

But Otis's most avid supporter was an angry, disheveled thirty-nine-year-old, whose ragged clothes, poor grooming habits, and foul mouth repelled all but the equally ill-kempt laborers of the Boston waterfront. Claiming to despise money, Samuel Adams, Jr. had graduated from Harvard in 1740, ranked at the bottom of his class socially. He nonetheless sought and found a job at the great merchant house of Thomas Cushing, Sr., a friend of Adams's father, the brewer. Within a short time, however, Cushing dismissed young Adams for writing political tracts instead of

keeping company ledgers. Adams, Sr. then gave his son some money to start a business, but Sam loaned half the money to a friend who lost it, and Sam promptly lost the rest on his own. Sam then went to work in the family brewery but ignored his job to found a political club with other young malcontents and write political diatribes in a newspaper they published. Still filled with bitterness over his father's fate in the Land Bank collapse, Adams fixed on destroying Thomas Hutchinson and the other mercantile aristocrats, but his groundless editorial attacks repelled readers, and his newspaper went bankrupt after a year.

Sam Adams's parents died in 1758, and although young Samâby then thirty-sixâinherited the brewery and the family's fine home on Purchase Street, he ran the brewery into bankruptcy and allowed the house to deteriorate. Evidently unconcerned with earning money, he married, fathered two children, and, after his wife's death, raised his children in abject poverty. Friends of his father found him a sinecure as a city tax collector to ensure his earning enough to feed his children and his slave, but within a short time, his ledgers showed a shortage of £8,000, representing tax monies he had either failed to collect or had embezzled.

Initially repelled by Adams's person, Otis only embraced his fellow Harvard alumnus after discovering Adams's skilled pen and his connections with a huge, disenfranchised, and underpaid population of shipfitters, rope makers, sail makers, caulkers, sailors, clerks, and longshoremen who worked Boston's waterfront. The waterfront workers would soon prove a natural and powerful constituency as foot soldiers for Sam Adams's political movement. Although Adams abstained from alcohol, he spent evenings roaming the city's taverns, where, according to his distant cousin John Adams, patrons “smoke tobacco till you cannot see from one end to the other. There they drink flip

*

I suppose, and there they choose . . . selectmen, assessors, collectors, wardens, fire-wardens, and representatives.” Sam Adams patrolled the taverns to make certain that they chose the men he wanted them to choose and ensure his own ambitions for political power.

At the time, John Adams was a young lawyer, still in his twenties. A graduate of Harvard's class of 1755, he grew up in farm country near Braintree, Massachusetts. Descended from Henry Adams, an English farmer who emigrated to America in the early 1600s, John Adams taught school after leaving Harvard and flirted with the ministry before deciding

to study law. Pledging “never to commit any meanness or injustice,” he believed that the practice of law “does not dissolve the obligations of morality or of religion.”

17

He gained admission to the Boston bar late in 1758 and was still building his practice and writing an occasional, thoughtful essay on public affairs for newspapers when British Prime Minister George Grenville coaxed Parliament into passing a set of tax laws to supplement the Molasses Act and add duties to a range of consumer goods, including tea. The growing popularity of tea made higher prices particularly unwelcome, and together with the other tax increases, any tax on tea threatened to incite a storm of protests.

Â

____________

*

“A mixture of beer and spirit sweetened with sugar and heated with a hot iron.”â

The Shorter Oxford Dictionary

The Miserable State

of Tributary Slaves

T

he defeat of the French and cession of New France to Britain provoked an all-but-immediate conflict with Indians in the West. When the French army evacuated western military posts, a wave of English colonists migrated westward, threatening to overrun tribal lands. Outraged by the incursions, Ottawa Chief Pontiac organized western tribes and launched a massive attack on undermanned British posts, destroying seven of the nine British forts west of Niagara. Stiff resistance kept Fort Pitt and Detroit in British hands, but the Indians decided to await victory by attrition and laid siege. Major General Jeffrey Amherst suggested breaking the siege by sending blankets laden with small pox germs into the Indian camps, but the British commander in the West overruled him.

Incensed by the Indian attacks and the Pennsylvania Assembly's failure to protect white settlers, a mob of fifty-seven drunken frontiersmen from Donegal and Paxton townships massacred twenty unarmed Conestoga Indians northwest of Lancaster. The attack incited some six hundred farmers and frontiersmen in the area to take up arms and march to Phila delphia, determined to seize control of Pennsylvania's government. Only the intercession of Benjamin Franklin and a group of prominent Philadelphians

with some barrels of rum at the city line convinced the “Paxton Boys” to turn back and stagger home with pledges of more military aid for westerners and more equitable representation in the state legislature.

Five months later, British army regulars arrived to relieve both Fort Pitt and Detroit, and after a series of bloody encounters, Pontiac surrendered, but the campaignâalong with the serio-comic adventure of the Paxton Boysâconvinced British commanders that ill-trained colonial militiamen were incapable of defending frontier settlers against Indian attacks. Only a permanent, regular-army presence would permit development of the West and establishment of permanent settlements.

With Britain all but bankrupt from the war, however, the costs of maintaining a permanent army in America to defend colonists impelled Prime Minister George Grenville to try to force Americans to share the costs of their defense. The French and Indian War had left the government more than £145 million in debt, of which £1,150,000 had gone to the colonies for war costs. While colonial merchants had reaped fortunes by smuggling goods to the enemy, Parliament had crushed Englishmen with an avalanche of taxes that swept 40,000 people into debtor's prisons and provoked antitax riots across England. Englishmen had been paying twenty-six shillings a year per person in taxes to the government, compared to 1 shilling a year, or one-twentieth of a pound, per person in America, where the average annual income was about £100. With regional tax riots in Britain threatening to explode into a national rebellion, Grenville had no choice but to ease England's tax burden.

Formerly first lord of the treasury and chancellor of the exchequer, Grenville had become prime minister in April 1763, inheriting an annual budget that included nearly £1 million to support the king and £372,774 for American military garrisons. Described as “one of the ablest men in Great Britain,”

1

he could do little about the king's spending, but he could, at least, force colonists to pay for their own defenses. Taxes were not new in America, but, like the Molasses Act, they were indirect taxesâimport duties that merchants were supposed to pay but had evaded by smuggling or by bribing customs officials.

Britain had sent ten thousand British regulars to guard western frontiers against Indian attacks, while the British navy patrolled Atlantic coastal waters

and freed Americans to enjoy a prosperity that no colony had ever before experienced in world history. With land the basis of all wealth in the Americas, the crown had made millions of acres of wilderness available to every white freeman for the taking, and thousands had reaped a rich harvest of grain, lumber, pelts, furs, and ores. Grenville felt it only just that they share some of their wealth with the mother countryâand the vast majority of Englishmen agreed.

The first of the Grenville tax proposals was the American Revenue Act, which aimed at strict enforcement of customs-revenue collection and a substantial increase in American contributions to British government costs. The act outraged Americans. The prospect of stricter tax collections, Governor Bernard wrote to the Board of Trade in London, “caused a greater alarm in this country than the taking of Fort William Henry [by the French] in 1757. . . . The merchants say, âThere is an end of the trade in this province . . . it is sacrificed to the West Indian planters.'”

2

A correspondent for the

Boston Evening Post

warned against “making acts and regulations oppressive to trade,” while a protest in the

Pennsylvania Journal

declared, “Every man has a natural right to exchange his property with whom he chooses and where he can make the most advantage of it.”

3

The issue of so-called natural rights had been infecting western European, English, and American social and political thought periodically for more than a century, but it gained new virulence in 1762 with the appearance of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's

Le contrat social

(“The Social Contract”). Its opening words stunned the world with a revolutionary new sociopolitical concept: “Man was born free and everywhere he is in chains.”

4

Widely misinterpretedâespecially in AmericaâRousseau seemed to imply that, having been born in a natural state, independent of all authority other than God, man has the right to remain so. “Renouncing one's liberty,” he goes on to say, “is renouncing one's dignity as a man, the rights of humanity and even its duties.” To Rousseau's own consternation, however, such phrases spread across the western world without any of his qualifying words. Although Rousseau asserted that “no man has a

natural

authority over his fellow man,” he insisted that man's survival depends on a “social compact, in which he surrenders many of his rights to the state.”

5

In his argument against writs of assistance, Otis carefully omitted the Rousseauvian

concept of the necessary alienation of some individual liberties to the state to ensure protection of other individual liberties.

“Liberty is the darling idea of an Englishman,” scoffed Peter Oliver, who was on the Massachusetts Executive Council at the time of the writs of assistance case. The son of the great Boston merchant Daniel Oliver and grandson of Massachusetts Governor Jonathan Belcher, Oliver had graduated from Harvard at the head of his class in 1730, earned his M.A. three years later, and married the daughter of another prominent Boston merchant, Richard Clarke. By 1761, when Otis took up the cause of merchants opposing writs of assistance, Oliver had inherited his father's merchant-banking house with his older brother Andrewâalso a Harvard graduate. In 1744 they had bought an iron works, added eight water wheels, and transformed it into North America's first rolling mill and largest iron works. After amassing a fortune supplying the Massachusetts militia with cannons during the various wars with the French, Oliver retired to the country to focus on scientific agriculture. Later, he entered public service as a justice of the peace, then, in succession, as a member of the provincial House of Representatives, a member of the Executive Council, and chief justice of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.