American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (29 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

The money isn’t just in the weapons. The officers need ammo, both to use the gun and, just as important, to practice with. And practice takes time—every hour a policeman spends on the firing range is one less hour on the street, which means someone else has to do his job there.

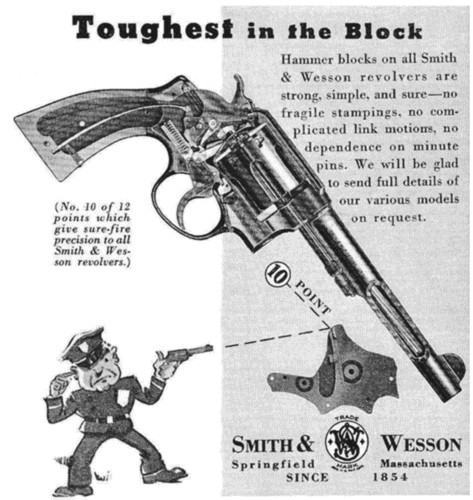

So police weapons evolved toward efficiency, and just enough stopping power to get the job done. While rifles, shotguns, and automatic weapons fill certain roles, the sum of what a policeman needed meant a pistol would be his primary weapon. And if you were thinking about a pistol for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, odds are you were calling to mind a product from one of two companies: Colt, or its chief competitor, Smith & Wesson.

Colt scored big with their revolvers in the mid-nineteenth century, but Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson were right up there with them. The New England gunmakers teamed up in 1852 in a failed attempt to launch the lever-action “Volcanic” repeating pistol and rifle with a fully self-contained cartridge. As we’ve seen, the business flopped and Oliver Winchester ended up with the company. But Smith and Wesson didn’t ride off into the sunset. The pair patented a rimfire cartridge in 1854, then used it to design a new revolver. In 1856, their new company, Smith & Wesson, unveiled the Model One Revolver. The .22-caliber seven-shooter launched the company on a road that would include a number of historic guns.

Coke versus Pepsi, Chevy versus Ford, Colt versus Smith & Wesson: the all-American pair duked it out for decades. Their guns got better thanks to old-fashioned competition. After making improved versions of the Model One, Smith & Wesson topped itself in 1867 with the Model 3 .44, the first big-bore cartridge-firing revolver. Colt came back with the classic Single-Action Army revolver of 1873. Then they followed up with the first successful double-action revolver, the Model 1877. In 1889, Colt unveiled a new line of Army and Navy revolvers, the first double-action revolvers with swing-out cylinders.

Smith & Wesson

On a swing-out frame, the cylinder pivots away from the body, making it faster to load than a fixed frame gun. At the same time, the frame is stronger than the break-top, a design which also makes for quick reloading by letting the cylinder and the front of the gun forward.

In 1899, Smith & Wesson came out with Model 10, also known as the Military and Police revolver. Colt followed with the New Police, the Police Positive, and then the Colt Official Police.

The weapons from both companies have a lot in common. Together they defined the category of police handgun, and even the word “revolver” for sixty or seventy years. And through most of that time, they shared one critical ingredient: the .38 Special cartridge.

The family of .38-caliber bullets can be almost as confusing as the guns that use them. It probably won’t help to mention that the rounds were first supplied to replace the old ammo used by .36-caliber Navy revolvers. It

especially

won’t help to point out that the .38 round’s diameter is

really

.357—exactly because of that heritage. But those are the facts. The family includes the .38 Special, the .38 Short, .38 Long, and .357 Magnum, all at the same diameter. There are a bunch of cousins and near-strangers under each heading.

The .38 Special cartridge was one answer to the question of how to stop raging maniacs, the same problem the Colt 1911 was invented to solve. The .38 Special was more powerful than the .38 Long, which was a bit stronger than the .38 Short. First filled with black powder, smokeless powder became the standard about a year later. The .38 Special cartridges packed enough wallop for a while. But when stopping power became an issue again, improvements led to the .38 Special +P and .357 Magnum rounds.

Colt’s history gave it a leg up in the police market. The Colt 1911 also helped with what marketers call a halo effect. It was like Ford or Chevy with NASCAR. Associating with a wartime hero made the other guns look that much better.

But it wasn’t just the weapon’s marketing that made it popular. “As a personal defense weapon, Colt’s Official Police with a four-inch barrel is as dependable a gun as you could find,” wrote police weapons expert Chic Gaylord. “The Colt Official Police revolver in .38 Special caliber with a four inch barrel and rounded butt is an ideal service weapon for densely populated metropolitan areas. The Colt Official Police is probably the most famous police service arm in the world. It is rugged, dependable, and thoroughly tested by time. It has good sights and a smooth, trouble-free action. This gun can fire high-speed armor-piercing loads. It can safely handle hand loads that would turn its competitors into flying shards of steel. When loaded with the Winchester Western 200-grain Super Police loads, it is an effective man-stopper.”

By 1933 the Colt Official Police was standard issue for the police forces of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Los Angeles, plus the state police of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and Connecticut. The FBI issued the gun to its agents.

The standard pistols were meant to be carried in holsters at a policeman’s hip, and had barrel lengths varied from four to six inches. As a general rule, the longer the barrel, the more accurate the gun was likely to be in the average policeman’s hands. On the other hand, the longer the barrel, the harder it was to get out of the holster.

Both Colt and Smith & Wesson also came out with short-barreled “snub-nosed” pistols. These were usually meant to be carried under clothes or in a hidden holster as a backup weapon. In his patrol days, my SDPD friend Mark Hanten carried a Smith & Wesson 342PD in an ankle holster as a backup weapon, and frequently carries it as an off-duty gun as well. The J frame—the company’s generic term for the small size, post-WWII guns—was popular with police chiefs, detectives, and others who needed a weapon with them but didn’t want one that was too conspicuous.

The downside of the smaller guns is the kick that they have when firing. Mark used a .38 +P; think of it as a .38 Special round on steroids. It let you know you’d fired when it went off. “It’s the kind of gun that you want to have but never want to shoot,” as Mark puts it.

NYPD officers, 1964.

Library of Congress

The granddaddy of the snub-nosed guns was the Colt Detective Special, also known as the “Dick gun” since it was first worn by detectives who were carrying it in concealed holsters. Introduced in 1927, the little wheel gun, like its big brothers, was popular in a lot of old movies. Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Charlton Heston, Chuck Connors, Burt Lancaster—all packed the snub nose. A lot of the same stars had the bigger Colt Official Police or some other version of the .38 Special in different films.

The .38 Specials were solid and reliable guns. They worked well for most police forces right through the 1950s and early 1960s. They were also more or less the weapons the police faced, when they encountered weapons at all. But little by little, more powerful guns popped up in the hands of criminals. Most police didn’t realize it, but by the late sixties they had fallen behind the times.

Then one day they got a wakeup call in the form of a radio bulletin: Officers Down.

A number of serious shoot-outs and cold-blooded murders had a big impact on police thinking. One of the most famous happened in 1970, when four California Highway Patrol officers were killed in a shoot-out with suspects from a road rage incident. The two men who were stopped turned out to have a wide range of weapons, from a .38 Special to a sawed-off shotgun. After that, police departments began rethinking weapons and procedures, both.

Things kept ratcheting up. Like a lot of other police officers, Bob Owens, a lieutenant with the Dallas City Police Department, points to an FBI shoot-out in 1986 as the real turning point. Two Florida felons took on eight FBI agents in a gunfight outside Miami and outgunned them with a shotgun and a Ruger Mini-14 semi-automatic rifle. Before the fugitives were finally put down, two FBI agents were killed and five others wounded.

While .38 Specials were used by lawmen in both incidents, even more powerful weapons were outclassed. Rounds from automatics and .357 Magnums didn’t do the damage that police thought they would. More importantly, the training that even the FBI agents received was faulted.

“Training’s a key thing,” says Lieutenant Owens, who as you might have guessed is a friend of mine. “It’s time-consuming, though, and it takes officers off the street. It’s hard to keep things balanced.”

Owens’s department uses training that is a lot more realistic than in the old days, when policemen busted paper firing at targets on the range. Trainers now try to anticipate what situations officers might encounter, and try to make things as realistic as possible.

The other half of the equation is getting law enforcement the tools they need to do the job.

Gun manufacturers had seen the problem coming. Smith & Wesson introduced the .357 Magnum cartridge and the large-frame .357 Combat Magnum/Registered Magnum revolver in the 1930s. Colt cooked up the .38 Super Automatic round, capable of penetrating both bullet-resistant vests and automobiles. But many departments didn’t have the money to refit their forces.

“At a time when full-power ‘big-bore’ handgun rounds ran in the 300 to 350 ft/lb. muzzle energy range, S&W upped the ante to over 500 ft/lbs,” wrote NRA firearms historian Jim Supica in 2005. “Results of actual law-enforcement shootings suggest that the .357 magnum round, with 125 grain hollow-point loads, may be the most effective ‘stopper’ still today.” Maybe, but .357s were used in both the California and Miami incidents, with mixed results. While training was absolutely part of the problem, police not only needed bigger bullets, but they needed more of them. Revolvers carried too few bullets and were too slow to reload when you were facing a determined criminal.

Owens carried a .357 Magnum for a while on the force, and remembers that some departments used what are called dump pouches to carry speedloaders. The speedloader held an extra set of bullets, and a practiced cop could slide them into his revolver fairly quick under the best conditions. The problem is, few gunfights are ever held under the best conditions. Owens would often find the bullets fell out of the loader during a patrol. Luckily for him, he never needed to use it.

Semi-automatic pistols were the obvious solution. They held more cartridges and were quicker to reload. Equipped with the right bullets, they had sufficient stopping power against all but the most well-armored opponents.

But getting new guns for an entire police force was an expensive proposition. In Dallas, officers were helped by H. Ross Perot, who after hearing how the locals were outgunned, bought every officer an automatic of his choice. My friend Rich Emberlin still remembers the Sig Sauer Mr. Perot bought him; it was a 9mm semi, and certainly a fine weapon. But even the semi-automatics were soon outclassed. Rich tells a vivid tale of the day 9mm subsonic rounds from a friend’s gun simply bounced off the head and body suspect during a desperate shoot-out. So it’s no surprise he traded his original Sig for a model that fires larger rounds. It’s almost like a chess match—the bad guys counter every move the good guys make.

There is no one universal police gun or caliber anymore. Police departments use a wide range of pistols, including ones made by Smith & Wesson and Colt. But given its popularity, we can’t take off without mentioning the big ugly that changed a lot of minds about what a pistol should look like when it first came to the public’s attention in the mid-1980s: the Glock 17.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Gaston Glock was a plastics expert in Austria. He ran a company whose main products included curtain rods. An engineer by trade, he was talking to some Austrian military officers one day and heard them bad-mouth gunmakers for failing to produce a handgun that could meet their requirements. That got him thinking: Why not make a gun? Not just any gun, but the

perfect

gun.

Glock bought a bunch of pistols, stripped them down and put them back together. He checked every detail. He tinkered and researched, asked questions and messed around some more. It was easy to list what military people wanted in a handgun: a high-capacity magazine, light weight, accuracy, safety, and simplicity. It should be ready to fire at any time, but be safe otherwise.