American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (15 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

But it wasn’t the Gatling’s awesome firepower that would have saved Custer. It was the fact that the bulky Gatlings, even when disassembled for portability, would have slowed his march to Little Bighorn long enough for his forces to consolidate. Reinforcements would have arrived in time. Custer would have hours to spare to formulate a coherent plan of action.

But time was the reason Custer left them behind in the first place. He figured they’d slow him down.

On second thought, maybe there was no hope for Custer at all. He was in too much of a hurry to meet his fate.

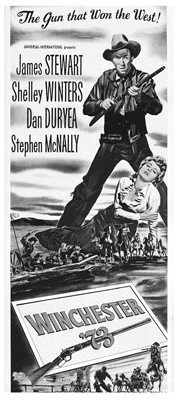

Dubbed “the gun that won the West,” the Winchester Model 1873 was an instant hit, destined to be a long-running best-seller for the company. The first cartridge it fired was a .44–40 Winchester center fire round, which proved particularly popular with people who owned revolvers in the same caliber. Winchester soon produced rifles in other calibers, making it possible for more gun owners to use the same bullets for their long gun and their pistol.

Other models followed. Winchester developed the 1876 with an enlarged and strengthened receiver, which allowed for larger and more powerful cartridges. Eventually available in a series of calibers ranging from .40–60 on up to .50–95 Express, the gun packed enough wallop to make it suitable for buffalo hunting. The 1876 and the 1886 that followed were versatile and powerful rifles, and straddled the transition from black powder to smokeless.

Winchester lever-action rifles became the prized possession of ranchers, movie stars, and presidents alike. The Winchester Model 1892 Lever-Action Repeater was the favorite of sharpshooter Annie Oakley and tagged along in Admiral Robert Peary’s baggage on a trek to the North Pole. Winchester sold a million of those guns. The Model 1894 was an even hotter seller, with more than 7 million produced in its different forms, making it the number one sporting rifle in history. Though it was first built to fire black powder rounds, it switched easily to new smokeless cartridges. In the United States, the Winchester 94 .30–30 combo became synonymous with “deer rifle.” You can still buy one new, fresh from the factory.

But my all-time favorite Winchester repeater has to be the Model 1892. If you’ve watched only John Wayne movies, you’ve probably seen the gun. It has an oversized loop trigger guard that looks like a miniature metal lasso under the stock. Unlike the 1876 and 1886 models, the 1892 was made to handle shorter rounds, again allowing a frontiersman to carry the same bullets for pistol and rifle.

For years, a friend of mine had a fine example of an 1892 sitting in his weapons vault. This particular version was a specially made Winchester John Wayne Commemorative edition. It had special engraving on the metal and a silver indicia on the stock showing the Duke’s profile. Any time I’d go over to the vault, just about my favorite thing would be to take that rifle and rack it. I’d work the action like I was riding with the Duke himself.

One day, we were in there talking, and I went over to the gun. My friend looked at me a little funny, so I stopped and backed away.

“Take it,” he told me. “It’s yours.”

“Huh?”

“You like that gun so much,” he insisted. “Take it.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

I did. And I’ve enjoyed it ever since.

You can’t make a Western without a Winchester. Above, John Wayne takes aim in El Dorado; below, in the hands of Jimmy Stewart in

Winchester

’73.

Paramount Pictures

In the early morning hours of Valentine’s Day, 1884, a young politician sat at the bedside of his dying wife, trying to make sense of the way joy had suddenly turned to tragedy over the past twenty-four hours. He had returned home to New York City through a terrible fog and storm after receiving a wire that his wife had given birth to their first child. Now he was shocked to find his wife dying of kidney failure, then known as Bright’s Disease. Downstairs, his mother was in the final stages of typhoid fever.

His daughter was healthy, but both his mother and wife would die that same day.

Devastated and utterly alone, the young man left politics and New York. Wandering the American West in search of a new life, he settled into the life of a rancher and outdoorsman in the badlands of Dakota Territory.

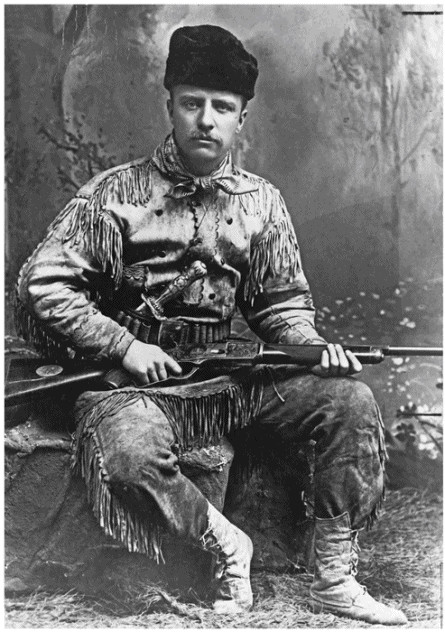

The man was Theodore Roosevelt. TR went on to become America’s youngest president and a Nobel Peace Prize winner—as well as a lifetime National Rifle Association member, world-famous big-game hunter, gun collector, and the biggest celebrity endorser that the Winchester firearms brand ever had. “The Winchester,” he wrote, “is by all odds the best weapon I ever had, and I now use it almost exclusively.”

As a hunter out West, Roosevelt liked not only the punch but the utility of the 1876 Model. “It is as handy to carry, whether on foot or on horseback, and comes up to the shoulder as readily as a shotgun,” he declared. “It is absolutely sure, and there is no recoil to jar and disturb the aim, while it carries accurately quite as far as a man can aim with any degree of certainty.” The .40–60 Winchester, he noted, “carries far and straight and hits hard, and is a first-rate weapon for deer and antelope, and can also be used with effect against sheep, elk, and even bear.”

Teddy Roosevelt photographed in 1895 with his favorite gun, a Winchester 1876 Deluxe.

Library of Congress

In the West, Roosevelt found his reason to go on living. Hunting inspired him. He was a cowboy poet when it came to guns. “No one but he who has partaken thereof can understand the keen delight of hunting in lonely lands,” Roosevelt wrote. “For him is the joy of the horse well ridden and the rifle well held; for him the long days of toil and hardship, resolutely endured, and crowned at the end with triumph. In after years there shall come forever to his mind the memory of endless prairies shimmering in the bright sun; of vast snow-clad wastes lying desolate under gray skies; of the melancholy marshes; of the rush of mighty rivers; of the breath of the evergreen forest in summer; of the crooning of ice-armored pines at the touch of the winds of winter; of cataracts roaring between hoary mountain masses; of all the innumerable sights and sounds of the wilderness; of its immensity and mystery; and of the silences that brood in its still depths.”

In a few short years living in the West, Roosevelt became an authentic cowboy-rancher. He tamed bucking broncos, drove a thousand head of cattle on a six-day trail ride, punched out a cowboy in a saloon fight, and faced down Indian warriors. In 1886, with an 1876 Winchester in hand, he tracked and captured three desperadoes in the wilderness and marched them forty miles to face justice.

TR was witnessing the end of the American frontier. By 1890, fewer than a thousand American bison remained. Most of the available land claims had been staked. Countless lives had been claimed by nature, and by man. Yet for many settlers, and for millions more who would follow, the opening of the West offered opportunity and freedom. That frontier spirit is still branded into our national character.

As for Teddy Roosevelt, the West eventually repaired his spirit. He found his bearings again, returned to politics, and started a new family. He worked to clean up the New York City police department, then became an assistant secretary of the Navy. Wanting to see more action, he quit that job when war came, rounding up a group of volunteers to form one of the most famous cavalry units of all time.

And it was in a single hour in 1898, in the thick of combat, when Teddy Roosevelt would discover the key to the White House—while ducking bullets from a gun design that would help shape America into a world power.

“The French told us that they had never seen such marksmanship practiced in the heat of battle.”

—Marine Colonel Albertus Catlin, 1918

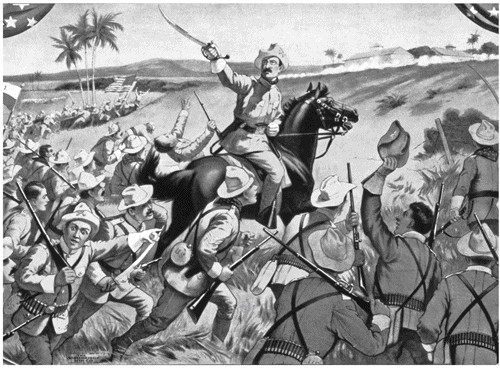

“I am the ranking officer here,” yelled Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, “and I give the order to charge!”

It was July 1, 1898. America was a few hours away from becoming a world power.

But it sure didn’t look it. Thousands of American troops were roasting in the hot sun below the hills guarding the eastern approaches to Santiago, Cuba. Palms and the nearby mountains made the place look like a picture postcard paradise. But the whizzing bullets and heat made it feel like hell.

The Americans were bunched up, clogged and trapped by their sheer numbers.

Bullets shredded the tall grass around them. “The situation was desperate,” wrote Richard Harding Davis, a reporter on the scene. “Our troops could not retreat, as the trail for two miles behind them was wedged with men. They could not remain where they were, for they were being shot to pieces. There was only one thing they could do—go forward and take the San Juan hills by assault.”

Roosevelt’s thick glasses fogged in the boiling humidity. He was leading a force of nearly one thousand “Rough Riders,” officially named the First United States Volunteer Cavalry. The handpicked, motley-crew cavalry regiment took Texas Rangers and Western cowboys and mixed them with East Coast Ivy Leaguers, polo players, and tennis stars. Not only were they a varied unit, they were on foot, except for Roosevelt. The rest of the unit’s horses were still back in Florida.

Mounted or not, they’d just be targets if they stayed where they were. But the American infantry officer at the head of the mass formation didn’t want to command his troops to move without orders from his superior. And his unit was in Roosevelt’s way.