American Eve (43 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

The first occurred when Harry’s faithful valet of eighteen years, William Bedford, died suddenly and mysteriously. Everyone suspected that the loyal Bedford had witnessed more than his share of Harry’s aberrant behavior, and wondered if his abrupt and final departure wasn’t part of some twisted Machiavellian plot by the Thaws to protect Harry’s tinseled image as defender of the blameless and the innocent. Apparently, no one was aware of any preexisting malady—except Harry, who blamed the district attorney’s office and its tactics for hastening Bedford’s death. Although the exact nature of the valet’s illness was never disclosed (peritonitis was suspected), Harry wrote, “Knowing that my poor valet was very ill and should be in bed and receiving proper care if his life was not to be endangered, the district attorney’s staff made him sit and sit in their offices for days and days. Mortally brutal, they made him sit when deadly ill until he had to be taken to the hospital at once. He was operated on the next day. The following day he died.”

This happened only one week after Harry’s arrest, and to an already traumatized Evelyn, Harry seemed disturbingly and incomprehensibly unemotional about the death of Bedford, the man who had been closer to him than anyone (save his mother) for half his life. The only emotion he showed was to rant at the D.A. “and his minions.”

Coming hard on the polished heels of Bedford’s suspicious demise was the abrupt resignation of Evelyn’s maid, Nellie Leahy, who had been with her for more than a year. Nellie was “wrought up” over the “unintentional murder” of White. Bedford’s sudden death, coupled with feeling a chill on a warm day, stoked Nellie’s Irish superstitions. Convinced it was time to leave, she came up to Evelyn in the drawing room of the hotel, blurted out, “Someone has walked over my grave!” and promptly quit. Harry maintained that the district attorney’s office had arrested one of her relatives as a way of suppressing any favorable testimony she might offer, “in that way getting rid of her as they did of Bedford, even if it was not so drastic.”

“I TOLD YOU SO”

In spite of such disturbing events, for his part, Harry seemed annoyingly cheerful and buoyant to Evelyn when she came to visit him in his cell: “He had no doubt as to the righteousness of his act or . . . its wisdom. He never then or at any subsequent time expressed the slightest regret for his act.” (One of the few times in his life that Harry ever even alluded to the incident, or so it has been told in a now famous anecdote, occurred in Florida, near the end of his life. Supposedly, when confronted with a monstrosity of a building newly erected on the fringes of Miami Beach, Thaw remarked to a companion, “I shot the wrong architect.”)

But if Harry was suffering at all in prison, and on most days it didn’t seem so to Evelyn, she was suffering a far more miserable and paradoxically public confinement, having merely been maneuvered from one gilded cage to another. Even when surrounded by the mounting number of hangers-on who battened themselves to the Thaws and their millions, Evelyn was utterly alone.

The attitude of the Thaw family following the murder was, not surprisingly, one of unwavering united support for Harry as they offered an ivy-covered uniform brick façade to the press and the public—Mother Thaw; the countess of Yarmouth; Mr. and Mrs. George Lauder Carnegie; Josiah Copley Thaw, Harry’s financier brother; and Edward, the youngest sibling. But their attitude regarding Evelyn was a relentlessly stinging and reproachful “I told you so.” Evelyn, subject to what she described as only a handful of “isolated instances of kindness,” soon saw that any small act of nicety on the part of the Thaws was the result of their realization, after consultation with lawyers, of how much depended upon her and her testimony.

Initially, Evelyn and Mother Thaw went together to the Tombs to visit Harry in a show of solidarity for the battalion of reporters who watched their every move. One of the days when Evelyn was still riding with Mother Thaw to the Tombs, their car was stopped in heavy traffic. A policeman strolled up to the car at the crossing, Evelyn having become a familiar figure to the police. Evelyn and the traffic cop chitchatted for a little while, although she noticed out of the corner of her eye that Mother Thaw sat with rigid face and stiff back in the corner of the automobile. When they had moved on, Mrs. Thaw turned to Evelyn with a shocked expression.

“Evelyn,” she said reproachfully, “how can you speak with these people? Don’t you realize the social position you hold?”

Having no illusions anymore about the social status of the Thaws, an angry Evelyn retorted, ”Mother Thaw, you have got to realize that the social position your son now holds is associated with the Tombs Prison.” She continued, telling the glaring woman that “with reporters watching our every movement and on the hunt for ‘copy,’ what kind of a story do you imagine it would make if I turned up my nose at men whose social position is, at the moment, infinitely superior to Harry’s?”

Mother Thaw remained unmoved, and sat like an Easter Island statue carved out of ebony instead of stone and covered in imported black lace.

Because Mother Thaw was spending the majority of her time in New York, she was unable to control the Pittsburgh press. It soon began to surface in the hometown papers that Harry K. Thaw had been for years considered more than just “a mild sort of degenerate.” The headlines read, “Pittsburgh Rent by Thaw’s Act.” To add injury to insult, the Thaws’ mansion had been burglarized the day after the murder and $60,000 worth of Mother Thaw’s jewels were stolen, the thieves having read about the family’s absence in the papers.

As for Evelyn, described in the Pittsburgh papers as the “Woman Whose Beauty Spelled Death and Ruin,” to the unsympathetic she was now Delilah, Jezebel, and Salome all rolled into one. Nor was she prepared for another blow—her family’s abandonment of her, the family she alone had supported throughout her entire adolescence.

At first, between visits to the Tombs to see Harry and meetings with other Thaw family members, between the preliminary consultation with a multitude of lawyers and questioning by the police, a preoccupied Evelyn didn’t notice her mother’s glaring absence from her side. Neither was she fully aware of her brother’s growing bitterness toward her. But Howard had grown extremely fond of White, whom he saw not just symbolically as a kind and indulgent father figure, but as the only father he had known since the age of seven. Howard, who had also become inseparable in the last few years from White’s secretary, Charles Hartnett, wanted to repay White somehow and felt it his duty to defend the name of the man who had played such a large role in his otherwise limited, fractured, and insignificant life. For nineteen-year-old Howard (the same age as White’s son Lawrence), this meant shunning his sister, the person he too came to view as responsible for White’s tragic end. It was Harry, in a rare moment of clarity, who suggested in a letter to one of his lawyers that his lawyer “quietly call” on Evelyn’s new stepfather, Charles Holman, to intervene and take care of Evelyn. But if the lawyer ever made the overture to Holman, there was no response, either from the Mr. or the Mrs.

On any given day, Harry was champing at the bit to go to trial; in fact he looked forward to finally having a public forum to expose the “set of perverts” who preyed on upright and chaste young girls, as Evelyn once was. He was sure that the man in the street supported him and Evelyn, as did “every policeman and detective in New York City.” “And,” he was sure, “the great tide of sentiment could not be turned back.” So the idea that there might be no trial, that he would somehow be forced into an asylum not as the conquering hero but as a lunatic murderer, sent him into paroxysms of rage and tears. He went into a purple frenzy at the thought that the public might think he was sitting in a straitjacket and drooling into a spittoon.

The media seemed as schizophrenic as Harry in trying to describe the role of the principals in the case. While many tried to run with the Edwardian notion that Harry was Sir Galahad, others began to report how he had been involved all his life in “costly and humiliating escapades” from which his poor mother had to rescue him, with Mother Thaw often covering exorbitant checks (and hiding his peculiar moral bankruptcy), which Harry tried to cash with insufficient funds on both counts. One story asserted that when in school, he had “taken courses in dissipation,” even though Harry believed that he had thousands of years of history on his side, going all the way back to Cicero: “When life or liberty to self, or in those we must protect, is in danger by robbers and enemies, any means is allowable to defeat their nefarious ends.”

There was of course other front-page news. A Pennsylvania Railroad express train had rolled into the Philadelphia station with a dead engineer standing at the lever. The man had apparently had a heart attack somewhere between Philadelphia and Trenton. The heroic fireman who had noticed the unusual speed of the train as it approached the station jumped into the cab and stopped the train as it barreled into the train yard, barely avoiding disaster. But there would be no one to stop the Thaw engine as it gathered steam and threatened to crush any who might interfere with the wheels of their particular well-greased defense of heroic Harry Thaw, protector of wife and home. When two weeks became two months, the “Garden tragedy” was still dominating the headlines; little did anyone realize that it would continue this way, with only brief and intermittent periods of relative quiet, for two years.

The murder, coming as it did in the midst of insurance scandals, Roosevelt’s trust-busting, and the like, prompted the working class to suddenly look more critically at the “filthy rich.” As the young century progressed, one by one the wealthy and powerful were being knocked off their high horses, and increasingly it seemed the greater the fall, the more pleasure it afforded the common man. Uncommon wealth may still have been synonymous with superior social position, but it no longer meant moral superiority. In fact, the rich were experiencing a backlash. Whereas the nineteenth century had upheld the belief that God rewarded the deserving, the young twentieth century, disillusioned by the extraordinary and blatant immorality of the typical millionaire, destroyed that notion forever. New York City in particular, in the words of Irvin S. Cobb, was depicted as “a bedaubed, bespangled Bacchanalia.” It was, some glibly proclaimed, doomed to collapse like the Roman Empire.

And with the help of the “new Pandora,” in spite of what appeared in black and white in the press, there were far more shades of red than anyone could have predicted.

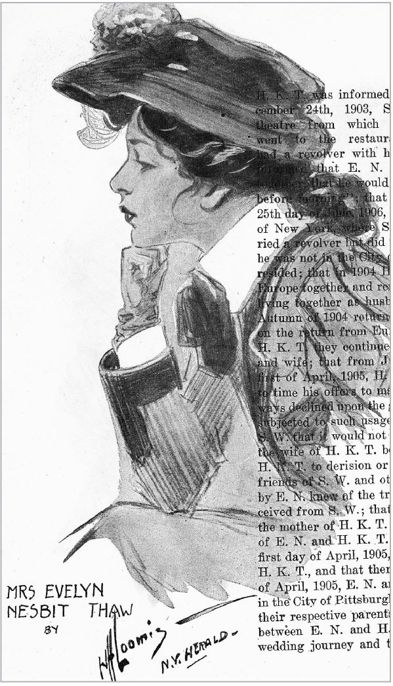

Newspaper illustration of Evelyn on the witness stand, 1907.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

A Woman’s Sacrifice

I must tell all that is to be told, because around this night . . . circled the tragedy which destroyed the life of one man, helped to undermine the reason of another, and dragged me into the fierce light of publicity and of criticism.

—Evelyn Nesbit, Prodigal Days

It is a frightening experience to hear a thought to which you have never given words babbled aloud in the street. . . . It sets you frantically anxious to amend, to contradict, to correct. Your little secret is everybody’s secret now. It has gained in importance, has been twisted in detail until it is like nothing you ever knew.

—Evelyn Nesbit, Prodigal Days

Absolutely no one was prepared for the incendiary media firestorm ignited by Stanford White’s murder, not even Evelyn, who had grown used to intrusive publicity and frequently boorish or questionable methods of investigation and speculation on the part of reporters. As she wrote, they could “cover a horse show and an electrocution in one day . . . and give no indication they are impressed by either.” But the “Garden tragedy” exploded with an unprecedented molten force upon an unwary public, whose growing taste for tabloidism became clear as they “gorged themselves on every morbid morsel.”

Much to her chagrin, it was Evelyn’s predicament that took center stage in what would become, among other things, a battle of the journalistic sexes—giving rise to a whole new form of reporting in America and a new labor force, “those women with three names”—the sob sisters.

THE SOB SISTERS

Nicknamed “The Pity Patrol,” the sob sisters shared a spiritual kinship with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “damned mob of scribbling women” fifty years earlier. As aspiring writers, their only hope to break through the male bastion of the fourth estate was to replace tough, cynical, hard-nosed coverage with a softer alternative, which in this case meant offering a “womanly perspective,” filtered through the sympathetic gauze of an overly sentimental style of writing befitting their “feminine skills” and “intuition.” Hired to cover the Thaw case by three of New York’s biggest newspapers, the sob sisters sprang up virtually overnight to provide day-to-day tear-jerking, heart-tugging reportage. Aided and abetted by the social and political climate of the day, the sob sisters entered the journalistic arena by fixing their sights on Evelyn (who would have preferred to remain in the shadows). And they did so with a florid, maudlin vengeance: