American Crucifixion (38 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

Unbeknownst to the Gentiles, and even to most Mormons, Brigham and the Twelve had decided to move to the Rocky Mountains, to one of two vast and uninhabited tracts of land: the Great Salt Lake Valley or Utah Valley, just to the north. “Uninhabited,” though, was a figure of speech; several Native American tribes frequented both valleys, which formally belonged to Mexico’s California holdings. But Mexico was busy losing a war to the United States, and Young and the Twelve correctly surmised that it would be several years before anyone bothered to lay claim to these arid, intermontane expanses. Getting there would be quite a trick. From Nauvoo, the trail led more or less due west, for 1,300 miles along the course of the Missouri, Platte, and Sweetwater Rivers. The last few hundred miles of the journey would require arduous mountain trekking, some of it through passes and along ranges known only to a small coterie of scouts and mountain men.

If the Saints knew anything about the land enclosed by the Rockies, they knew it was bleak. But once the Twelve announced their relocation plans, the church-owned

Nauvoo Neighbor

began publishing upbeat excerpts from the journals of legendary explorer John C. Fremont:

Nauvoo Neighbor

began publishing upbeat excerpts from the journals of legendary explorer John C. Fremont:

The Rocky Mountains . . . instead of being desolate and impassable . . . embosom beautiful valleys, rivers, and parks, with lakes and mineral springs, rivaling and surpassing the most enchanting parts if the Alpine regions of Switzerland. The Great Salt Lake, one of the wonders of the world . . . and the Bear River Valley, with its rich bottoms, fine grass, walled up mountains . . . is for the first time described.

The biblical nature of the proposed journey was lost on no one. Speaking to a general conference of the church in the fall of 1845, Apostle Heber Kimball announced that “the time of our exodus is come; I have looked for it for many years.” He continued:

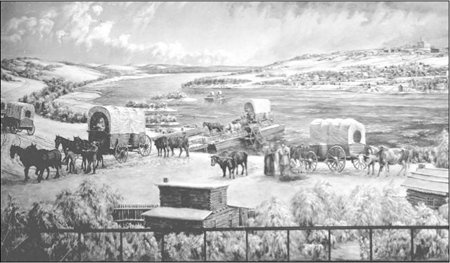

A famous painting by Lynn Fausett depicting the Saints’ first departures from Nauvoo to the Iowa Territory. In the background, the Nauvoo Temple is fully completed.

Credit: Utah State Historical Society

We want to take you to a land, where the white man’s foot never trod, not a lion’s whelps, nor the devil’s; and there we can enjoy it, with no one to molest us and make us afraid; and we will bid all the nations welcome, whether Pagans, Catholics or Protestants.

Young stalled for time with the Saints’ tormentors, in part to prepare for the daunting journey west—the Mormons built 3,400 wagons that winter—but also to complete the prophesied construction of the Nauvoo Temple. The Twelve had promised that Joseph’s secret temple endowment ritual, heretofore administered on the second floor of his general store, would be available to any Saint in good standing when the Temple was completed. The feverish construction finally ended in December, and the long-awaited “temple work” began. Husbands and wives were sealed in eternal marriage; plural wives were sealed to men “for time”; dead relatives were baptized and assured eternal life; and the Twelve introduced a ceremony of spiritual adoption, in which church leaders sealed friends and distant relatives to themselves as children. Most Saints were desperate to receive the basic endowment ritual and don their temple garments, which Joseph and the Twelve taught they would need to meet Jesus Christ in the final days, and to enjoy the prophesied exaltation. Over 5,000 Saints received their temple blessings in November and December 1845, with Brigham Young, Heber Kimball, and other apostles sometimes working twenty consecutive hours to process believers through the elaborate rites. By February 1, the temple work had ended, and the first Mormon companies assembled at the base of Parley Street to be ferried across the Mississippi to Iowa. The river was flowing, although it would freeze up later in the month, easing the way for the hundreds of wagons wending their way west.

On February 15, Brigham Young and his brother Joseph led a company of fifteen wagons down to the water’s edge. The Mormons were running six ferries, operating simultaneously, across the frigid river. Willard Richards and his eight wives filled two of the wagons lined up directly behind Brigham. Like many Saints, Young had failed to sell his Nauvoo home. The Mormons’ Hancock County tormentors often didn’t bother to bid on properties they knew would fall into their hands as soon as the Saints left the state. Brigham carefully maneuvered his oxen onto a broad flatboat, helped pole his worldly possessions out into the roiling current, and led the Mormons west, into the mainstream of American history.

* One disaffected listener, S. S. Thornton, wrote to his father-in-law that “Mr. Young had tried to mimic Joseph for several years . . . and on his return from Boston after [Joseph’s] martyrdom even went out to get a dentist to take out a tooth on the same side that Joseph lost one, to make myself appear as much like him as possible.”

* Following the dictates of the Plates of Laban, which forbade “every form of [women’s] dress that pinches or compresses the body or limbs,” Strang had a predilection for dressing women in pants and enforced a dress code on Beaver Island. Females had to wear ankle-length bloomers, which he called “Mormon dress.” A visiting Gentile wrote: “I do not object to the number [of wives assigned to] each man, but the trousers I do not like.”

14

THIS WORLD AND THE NEXT

Their innocent blood, with the innocent blood of all the martyrs under the altar that John saw, will cry unto the Lord of Hosts till he avenges that blood on the earth.

—Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Section 135

MORMONS HAVE A FERVENT, OFTEN BLOODY-MINDED, FAITH in retributive justice. Here is a letter sent to Nauvoo by James Sloan, a leading Saint missionary in England:

The Marquis of Downshire, who oppressed the Saints at Hillsborough in Ireland, has had the pleasure of his son, Lord William, being killed by his horse at a hunt in England, a few weeks past, and Mr. Reilly, his agent, who aided in their abuse, has received the third attack of some paralytic affliction and obliged to resign his office; his son again, who headed a mob to annoy the Saints and prevent preaching, has gone to Cork in bad health;

So much for them

. [Emphasis in original.]

So much for them, indeed. Why wouldn’t the Saints hope that God would square accounts with their oppressors? No one else would. Missouri simply expelled them by the thousands, killing dozens of Saints and confiscating hundreds of farms and homes without even a gesture of restitution. When Joseph Smith and his followers sought succor from the federal government, the leading politicians of the time told him, orotundly, to go to hell. The charade in the Carthage courthouse proved yet again that justice would elude the Saints in this world. So they hoped that God would act where man had failed them.

Apostle Heber Kimball wrote in his diary that “ever since Joseph’s death,” he and “seven to twelve persons . . . had met together every day to pray . . . and will never rest . . . until those men who killed Joseph & Hyrum have been wiped out of the earth.” In the feverish final months at the Nauvoo Temple, the more than 5,000 Saints who received the sacred endowment ritual also pledged Brigham Young’s oath of vengeance. “We are now conducted into another secret room,” one communicant wrote of the ceremony,

in the centre of which is an altar with three books on it—the Bible, Book of Mormon, and Doctrine and Covenants (Joseph’s Revelations). We are required to kneel at this altar, where we have an oath administered to us to this effect; that we will avenge the blood of Joseph Smith on this nation, and teach our children the same. They tell us that the nation has winked at the abuse and persecution of the Mormons, and the murder of the Prophet in particular; Therefor the Lord is displeased with the nation, and means to destroy it.

*

Eliza Snow, the Mormons’ leading occasional poet, who was a plural wife of both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, wrote a poem in 1862 explaining that the raging Civil War was God’s revenge on the United States. Writing from Salt Lake City, she intended to rebuke William Cullen Bryant’s widely circulated, pro-Union call to arms, “Our Country’s Call,” with her lines:

Its fate is fixed—its destiny

Is sealed—its end is sure to come;

Why use the wealth of poesy

To urge a nation to its doom?

. . . It must be so, to avenge the blood

That stains the walls of the Carthage jail.

“Salt Lake is to be and remain the single cheering oasis amid the universal National desolation in the years to come,” was the

New York Times

’s sardonic comment on Snow’s verses.

New York Times

’s sardonic comment on Snow’s verses.

Snow would have been aware of Joseph Smith’s remarkable “Civil War prophecy,” delivered on Christmas Day, 1832, during the Nullification Crisis, a furious dispute between South Carolina and Andrew Jackson’s federal government:

1 Verily, thus saith the Lord concerning the wars that will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina, which will eventually terminate in the death and misery of many souls;

2 And the time will come that war will be poured out upon all nations, beginning at this place.

3 For behold, the Southern States shall be divided against the Northern States, and the Southern States will call on other nations, even the nation of Great Britain, as it is called. . . .

In 1843, Joseph made another prediction that came true. He prophesied that his friend Stephen Douglas would later aspire to the presidency, adding: “If you ever turn your hand against me or the Latter-day Saints, you will feel the weight of the hand of Almighty God upon you.” In 1857, Senator Douglas did turn his hand against the Saints, now openly practicing polygamy in the Utah Territory. Douglas called Mormonism “a disgusting cancer” that “should be cut out by the roots.” Douglas lost the presidency to Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and died the following year.

There was no statute of limitations for a crime against heaven—the killing of a prophet who claimed to converse with God, with the Savior, and with the seers of the Old Testament. In 1901, fifty-seven years after Joseph’s death, a small newspaper in the Mormon enclave of Lamoni, Iowa, reprinted a brief obituary from Petaluma, California, and then added its own commentary. The original item reported that “Robert Lomax, the man who led the Illinois raiders in 1844, when Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet was killed is dead.” (Lomax’s name appears in none of the lists of mobbers assembled after the killings.) The California paper reported that Smith died after “a hard fight,” conveniently forgetting that he and his brother were murdered in cold blood.

The events were fresher in the mind of the

Lamoni Chronicle

writer, who correctly recalled that “there was no assembly of the Mormons in [Carthage] and no fight there.” The Iowa newspaper concluded:

Lamoni Chronicle

writer, who correctly recalled that “there was no assembly of the Mormons in [Carthage] and no fight there.” The Iowa newspaper concluded:

If Mr. Lomax was there and a leader of that band engaged in the unlawful and unholy work, the reckoning of justice for him and his work lies with the courts on the other side.

IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES, POWERFUL legends sprang up concerning God’s vengeance on the mobbers who killed Joseph and Hyrum. In 1952, church archivist N. B. Lundwall gathered the many legends into an entertaining book,

Fate of the Persecutors of the Prophet Joseph Smith,

which for many years enjoyed the status of most-stolen book in the Salt Lake City public library system. Numerous diarists recorded instances of “the Mormon curse,” a rotting of the flesh that struck down the men who had lifted their hands against the Prophet. (Perhaps the curse fulfilled Joseph’s recorded prophecy five days before his death that his tormentors “will be smitten with the scab &.”) The Indians reported that a man named Jack Reed, who supposedly helped kill Joseph, was so deformed that no white woman could look at him:

Fate of the Persecutors of the Prophet Joseph Smith,

which for many years enjoyed the status of most-stolen book in the Salt Lake City public library system. Numerous diarists recorded instances of “the Mormon curse,” a rotting of the flesh that struck down the men who had lifted their hands against the Prophet. (Perhaps the curse fulfilled Joseph’s recorded prophecy five days before his death that his tormentors “will be smitten with the scab &.”) The Indians reported that a man named Jack Reed, who supposedly helped kill Joseph, was so deformed that no white woman could look at him:

Other books

The Turquoise Lament by John D. MacDonald

Santiago Sol by Niki Turner

Fireworks for July: A Holiday Bites Vampire Paranormal Holiday Romances by Michele Bardsley

Saturday by Ian Mcewan

The Pursuit of Tamsen Littlejohn by Lori Benton

Her Ancient Hybrid by Marisa Chenery

The Face of Fear: A Powers and Johnson Novel by Torbert, R.J.

The Pillars of Creation by Terry Goodkind

Cinnamon Roll Murder by Fluke, Joanne

Guarding His Heart by Serena Pettus