Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (14 page)

In the reign of George II, murder trials took place on Fridays, the condemned being allowed to repent during the Sunday before being hanged the following day. On being informed of that, one felon requested that his execution be postponed for a day or so ‘because it was such a bad way of beginning the week!’

Martin Clench and James Mackley

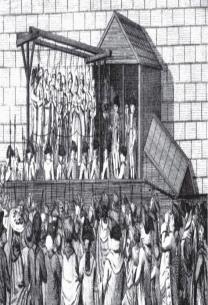

These two men, condemned to die on the scaffold on 5 June 1797, were standing on the drop while receiving spiritual comfort from the Newgate Prison chaplain and a Roman Catholic priest, while hangman William Brunskill and his assistant were adjusting the nooses about the victims’ necks. But someone had failed to check the bolts securing the trapdoors, and without warning they suddenly opened, plunging all six men into the yawning chasm, the two felons stopping abruptly as their nooses tightened, to die without absolution or blindfold. The other four, priests and executioners, plummeted on, to finish up in a struggling heap of arms and legs, profane oaths being emitted by at least two of them! The chaplain escaped with a few bruises, but the priest suffered severely when the two heavy executioners fell on top of him.

As reported in the

Derby Mercury

of 1723: ‘Last month Will Summers and John Tipping were executed for housebreaking. At the gallows the hangman was intoxicated with strong liquor and, believing there were three for execution, attempted to put one of the ropes round the parson’s neck, and was with much difficulty prevented by the gaoler from doing so.’

Newgate Gallows with Multiple Hangings

William Collier

George Smith of Dudley, the hangman who dispatched murderer William Collier outside Stafford Prison in January 1866, experienced a knotty problem when, having positioned the noose around Collier’s neck, he stepped to one side and withdrew the bolts holding the trapdoors up.

But let

The Times

of 13 January take up the tale:

‘The floor fell, but instead of the culprit’s head being seen just above the scaffold boarding as expected, it altogether disappeared. There was a cry, ‘The man’s down! The rope’s broken!’ The powerful tug which resulted from the falling of the culprit through the scaffold floor had, in fact, been too much for the fastening by which the rope held to the beam. The intertwined threads became liberated, the knot slipped, and Collier fell to the ground.

For an instant there was dismay, both upon and below the scaffold. The executioner was for a moment bewildered. He ran down the steps and, beneath the platform, he found Collier upon his feet, but leaning against the side of the boarding, the cap still over his face and the rope round his neck. He seemed to be unconscious, and the hangman turned again, not knowing what to do.

A new rope, delivered to the prison belatedly the previous evening, was immediately brought to the scaffold in order that the prisoner could be hanged again. A second time did the halter sway to and fro in readiness, again did the priest, turnkeys, culprit and hangman appear in the sight of the crowd. Their reappearance [on the scaffold] was the signal for an outburst of popular indignation. The hoots and calls were repeated until the drop again fell.’

When Dick Hughes, a housebreaker, was going to execution in 1709, he happened to meet his wife at St Giles where, the cart stopping, she stepped up to him and, whispering in his ear, said, ‘My dear, who must supply the rope to hang you, we, or the Sheriff?’ Her husband replied, ‘The Sheriff, for who else is obliged to find him the tools to do his work?’

Replied his wife, ‘Ah! I wish I had known so much before, ’twould have saved me tuppence, for I have been and bought one already.’

‘Well, well,’ said Dick. ‘Perhaps it mayn’t be lost, for it may serve for a second husband!’

Quoth his wife, ‘Yes; with my usual luck in husbands, so it may!’

Hannah Dagoe

Hannah was born in Ireland but had settled in London where she had obtained employment working in the fruit and vegetable market in Covent Garden. She became acquainted with a poor but hard-working widow by the name of Eleanor Hussey who lived by herself in a small apartment, and the unscrupulous Irish girl broke in while Eleanor was absent and stripped the apartment of every article it contained. Blame immediately falling on her due to her friendship with the owner, her rooms were searched and, the evidence immediately being forthcoming, Hannah was brought to trial at the Old Bailey, found guilty and sentenced to death.

She was a strong masculine woman, the terror of her fellow prisoners, and had actually managed to stab one of the men who had given evidence against her. By contrast, when eventually en route in the cart to the Tyburn gallows she showed little concern over her rapidly approaching fate and paid no attention to the exhortations of the priest who accompanied her.

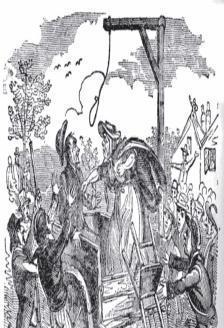

When the little convoy was halted beneath the gallows beam, however, somehow she got her hands and arms free and seized Thomas Turlis, the hangman; struggling wildly with him, she delivered a blow so violent that she nearly felled him. Shouting at the top of her voice, she dared him to hang her, declaring that come what may, he would not have her clothing afterwards, the garments to which he was entitled, and before he could restrain her, she tore off her clothes and threw them into the crowd, thereby adding considerably to their entertainment.

Hannah Dagoe En Route To Tyburn

During the hectic fight, it was reported that the escort of constables made no attempt to come to Turlis’ assistance; one can hardly blame them for deciding not to take on this wildcat within the confines of a small cart. Eventually, Turlis, bruised and battered, managed to overpower his prisoner and get the rope round her neck, but as soon as she felt the rough fibres touch her skin and the noose start to tighten, she threw herself out of the cart with such force that she died instantly, perishing more mercifully in fact than had she been hanged in the usual way, writhing for an interminable length of time at the end of the rope.

Margaret Dickson

The

Newgate Calendar & Malefactors’ Bloody Register

, published in 1891, devoted many pages to the crime and apparently miraculous recovery of Margaret Dickson after being hanged, though not without expressing a hint of Victorian doubt as to whether she really deserved it. Born early in the eighteenth century, Margaret Dickson was born in Musselburgh, about five miles from Edinburgh, and on reaching maturity she married a fisherman, by whom she had several children. Her husband was called up into the Navy and while he was away Margaret had an affair with a neighbour, by whom she became pregnant.

The

Calendar

explained:

‘In those days it was the law in Scotland that a woman known to have been unchaste should sit in a distinguished [conspicuous] place in the church on three Sundays, to be publicly rebuked by the minister; and many poor infants have been destroyed because the mother dreaded this public exposure, particularly as many Scotch ladies went to church just to be witnesses of the frailty of another woman, but were never seen there on any other occasion.

Margaret’s neighbours averred that she was with child, but this she constantly denied, though there was every appearance that might warrant the discrediting of what she had said. At length, however, she was delivered of a child; but it is uncertain whether it was born alive or not. Be that as it may, she was taken into custody and lodged in the gaol of Edinburgh. When her trial came on, several witnesses deposed that she had been frequently pregnant; others proved that there were signs of her having been delivered and that a new-born infant had been found dead near the place of her residence. The jury, giving credit to the evidence against her, brought in a verdict of guilty; in consequence of which she was doomed to suffer.’

In her favour it was subsequently reported that she behaved in a most penitent manner, confessed that she had been guilty of many sins and even admitted that she had been disloyal to her husband, but she steadfastly and constantly denied that she had murdered her child. She agreed that the fear of being exposed to the ridicule of her neighbours in the church had tempted her to deny that she was pregnant, and she said that when she went into labour, she was unable to summon the assistance of her neighbours; moreover she had lapsed into unconsciousness so that it was impossible she should know what became of the infant.

At the execution site she continued to protest her innocence, and expressed her sorrow for all her other sins. After being hanged for the requisite length of time her body was cut down and handed over to her friends, who put it in the coffin they had brought, and loaded it onto a handcart to be conveyed back to Musselburgh for burial. But, the weather being sultry, the cortège stopped at a village called Pepper-Mill, about two miles from Edinburgh, so that the mourners could refresh themselves at the local tavern. While they were drinking, one of them looked up to see the lid of the coffin move. Forcing himself, he cautiously and slowly slid the lid right back – whereupon Margaret Dickson immediately sat up and the rest of the company dropped their flagons and fled.

We have the

Calendar

to thank for describing what happened next: ‘It happened that a person who was drinking in the public house had recollection enough to bleed her [a universal ‘cure’ for just about everything in those days]. In about an hour she was put to bed, and by the following morning she was so far recovered as to be able to walk to her own home.’

Others in that century who recovered after being hanged were almost invariably re-hanged, but by Scottish law, ‘a person against whom the judgement of the Court has been executed can suffer no more in future, but is thenceforth totally exculpated; and it is likewise held that the marriage is dissolved by the execution of the convicted party; which indeed is consistent with the ideas that common sense would form on such an occasion.’

Half-Hanged Meg

So Margaret Dickson, having been convicted and executed, could not be prosecuted again, although the king’s advocate did file a suit alleging failure of duty against the Sheriff, the official directly responsible for executing her, even though that gentleman subcontracted the job out to the public hangman.

For once we have a happy ending, for Margaret was reunited with her former spouse, thousands turning up to witness the unique spectacle of a legally dead woman remarrying her own widower! Given the name ‘Half-hanged Meg’, she later had several more children and obtained a job selling salt in Edinburgh marketplace, her second and final death not occurring until 1753.

In 1811 it was recorded that ‘on Friday night, the evening before the execution of William Towneley at Gloucester, a reprieve for him was put into the post office at Hereford, addressed by mistake to the Under-Sheriff of Herefordshire instead of Gloucestershire; the letter was delivered to Messrs Bird and Wolloaston, Under Sheriffs for the County Hereford, about half past eleven on the following day. As soon as the importance of its contents were realised, a courier was humanely sent off with the utmost celerity to Gloucester, but the messenger arrived too late – the unfortunate man had been turned off twenty minutes before and was even then still suspended on the drop.’